Can social media clean up its act in time for the world’s biggest election? We’re about to find out.

About 900 million Indians are eligible to vote in the election, which will take place over about five weeks starting on April 11, and many more of them are online than during the last election in 2014. The scope for social media to be abused to manipulate voters has never been greater.

India is the world’s biggest market for Facebook (FB) and its messaging platform WhatsApp. It’s also one of Twitter’s (TWTR) most important markets. The country’s vote will present these companies with their sternest test yet.

Social media has faced increasing scrutiny over its role in elections ever since the 2016 US campaign, with Facebook in particular facing controversies like Russian accounts using their platform to sway voters and data from millions of users being shared with research firm Cambridge Analytica.

In elections in Mexico and Brazil last year, and Nigeria earlier this year, the company stepped up its efforts to stop abuse, though there were widespread reports that WhatsApp was used to spread fake news before the Brazilian vote.

India’s electorate is bigger than the combined population of those four countries.

“The enormity of it is quite well defined, and that is one of the reasons we think it is also one of our top priorities to keep elections safe and secure in India,” Shivnath Thukral, Facebook’s public policy director in India, told CNN Business.

“We’ve been working for months and applying different learnings from different parts of the world to … ensure that there is no abuse on the platform,” he added.

It won’t be easy.

The risk of violence

Indian politics is often fought along social and religious lines, and recent years have seen an uptick in violence against minority groups under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party.

The concern is that social media could be used to deepen those divisions, particularly through misinformation around the elections, and trigger violence.

“As the election approaches, this is going to become more aggressive and there’s always a chance that it can lead to loss of life or property,” said Pratik Sinha, founder of Indian fact-checking website Alt News. “In the heat of the elections, such kind of misinformation triggers any kind of violence,” he added.

WhatsApp, which has more than 200 million users in India, has already found itself at the center of the issue. Viral hoax messages on the platform were blamed for more than a dozen lynchings last year, with the victims falsely accused of child abduction.

Gilles Verniers, a professor of political science at India’s Ashoka University, said that social media has become “a constant megaphone” for political parties to amplify their messages.

“When those tools are used as weapons, not so much for smear campaigns or political satire but when it’s used as an instrument of social polarization … the damage goes beyond the framework of the election,” he added.

The megaphone is irresistible. Modi has over 46 million Twitter followers, more than any world leader except President Donald Trump, while main opposition leader Rahul Gandhi has already built up a following of nearly 9 million since joining the platform in 2015.

Social media in Indian politics burst onto the scene during the 2014 election, when Modi in particular dominated the conversation. This time around, his rivals appear to be catching up.

“The narrative of who’s up or who’s down, who’s smart and who’s not … that agenda gets set by social media in a way that TV was never doing before,” said Ravi Agrawal, author of “India Connected” and a former CNN India bureau chief.

In the last election, social media was harnessed to get the message out. This time, the dangers are coming to the fore.

“Any information automatically generates counter-information, and any fake information generates counter-fake information,” said Verniers. “In a way, you could say that Indian political parties are very good at interfering with their own election.”

Facebook’s Thukral downplayed suggestions that social networks are being weaponized.

“Of course there is a responsibility on us to make sure that the bad actors or the abuse of the platform is not becoming the bigger play. I would say that Facebook remains a platform where good ideas, good storytelling, good thoughts and ideas are being shared,” he said.

Millions vulnerable to misinformation

The sheer scale of India’s election presents a huge challenge for social media companies.

In 2014, India had around 250 million internet users. More than 560 million people are now online.

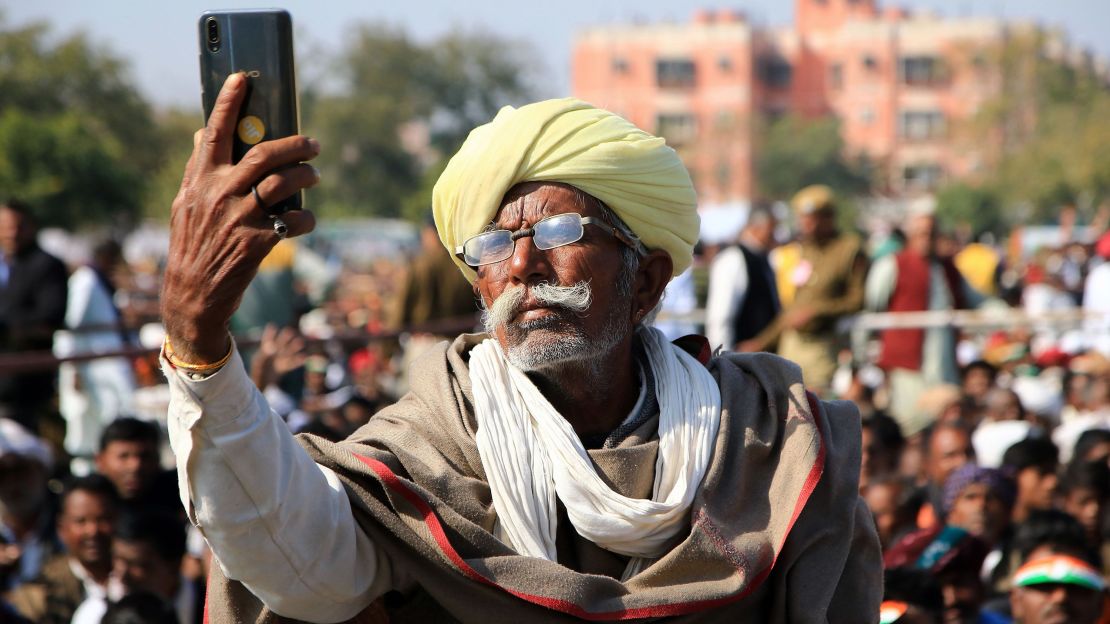

A fall of nearly 2,000% in the price of mobile data over the last two years, plus more affordable smartphones, have driven India’s internet boom. But hundreds of millions of Indians experiencing the internet for the first time are not educated, leaving them vulnerable to misinformation.

“Owning a phone and owning an internet connection has become much more affordable and pretty much everyone who has a phone has WhatsApp now, so there’s a much higher reach,” says Pratik Sinha, founder of Alt News. “At the same time the amount of internet literacy in large sections of the population is next to none.”

Alt News, founded two years ago, is one of several fact-checking websites that have launched since India’s last election in 2014, as viral hoaxes on social media become a bigger menace.

In the past month alone, the site has debunked a video from Sri Lanka being passed off as footage of Indian Hindus abusing Muslim women, a video from Russia that claimed to show drones Israel had sold to India, and several pieces of fake news about the recent military clash between India and Pakistan.

Much of the fake news that fact-checkers like Alt News unmask is targeted at political parties, including Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party and the Congress Party, led by Gandhi.

“I think political parties are motivated enough and have enough money that they will add more labor to ensure that the propaganda reaches the last person,” said Sinha. “I don’t think there’s anything that can be done as far as elections are concerned.”

Social media crackdown

Facebook and Twitter have taken several steps to make sure their platforms are not abused.

WhatsApp is using artificial intelligence to detect and ban accounts that spread “problematic content,” while Facebook is labeling political advertisements and partnering with Indian fact-checkers. Twitter has announced similar initiatives to crack down on “bad-faith actors,” and is also working with political parties and election authorities to ensure its platform isn’t compromised during the polls.

“We deeply respect the integrity of the election process and are committed to providing a service that fosters and facilitates free and open democratic debate,” Colin Crowell, Twitter’s global public policy head, said in a statement in February. “The 2019 [election] is a priority for the company,” he added.

Crowell recently appeared in front of an Indian parliamentary committee to testify about “safeguarding citizens’ rights” online, as did his Facebook counterpart, Joel Kaplan.

Facebook declined to comment on what was discussed, while Twitter did not respond to a request for comment.

But Kaplan said in a statement after the hearing that he was grateful to the committee for the chance “to show how we are preparing for the Indian elections and helping keep people safe.”

Political candidates will also be required to share details of their social media accounts with India’s election authorities, Chief Election Commissioner Sunil Arora announced Sunday. Parties will also be required to get political ads on social media pre-approved by the Election Commission and declare how much they have spent on social media advertising.

“Facebook, Twitter, Google and YouTube have committed in writing to ensure that any political advertisement published on their platforms will be certified,” Arora said.

The WhatsApp problem

WhatsApp responded to last year’s lynchings with several measures that it hopes will help during the election as well — labels on forwarded messages and an awareness campaign on radio, TV and newspapers.

The messaging platform also limited to five the number of chats a single message can be forwarded to.

But each WhatsApp group can have up to 256 people, meaning a message can still reach 1,280 people at the touch of a button.

“The velocity that misinformation gets once something is out there and it is something which captures people’s imagination, then it is shared like crazy,” said Sinha. “And it’s that velocity that one needs to arrest, so that the least amount of people are affected.”

Beyond the election

In many ways, the election will serve as a litmus test for how India’s internet — second only to China’s in size — will grow and progress in the future. The rapid boom in user numbers poses an ever greater challenge to the government and tech companies to keep them safe.

“The fact that all of this happening so quickly in India means that giant mistakes will be made and people will end up being misinformed in a mass way,” said Agrawal.

CNN’s Sugam Pokharel contributed to this report.