Sub-Saharan Africa has, on average, the worst healthcare in the world, according to the World Bank. It accounts for nearly a quarter of all disability and death caused by disease worldwide, yet has only 1% of global health expenditure and 3% of the world’s health workers.

Infrastructure is poor, making access to even the most basic medical care difficult.

But new technologies — from drones to apps and computer-controlled vending machines — are helping to break down these barriers and provide access to vital medicines for many more people.

Flying medical aid

In May, the South African National Blood Service (SANBS) announced that it would begin using drones to transport blood to tackle the high mortality rate among women during childbirth across the continent, says Amit Singh, head of drone operations.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 295,000 women died globally from mostly preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth in 2017, with roughly two-thirds of these deaths taking place in sub-Saharan Africa.

“This was [in part] due to the fact that blood could not get to the patient fast enough, as traditional transport means take far too long due to poor road infrastructure and the distance that needed to be covered,” Singh tells CNN Business.

The drone services — which are still undergoing tests with the Civil Aviation Authority — could overcome these problems. They can endure most weather conditions and only need five square meters (54 square feet) of flat surface to land — considerably less than a helicopter.

The SANBS plan follows the success of Zipline, a Californian startup that started delivering blood and vaccines in remote parts of Rwanda in 2016. In April, it expanded operations to Ghana, and now claims to serve 13 million people globally.

Doctors place orders through an app. Once they have been processed, medical products — which are stored centrally at Zipline’s distribution centers — are packaged and flown by drone within 30 minutes to any destination, then dropped from the sky with a parachute.

“Our just-in-time, instant drone delivery service cuts delivery times down from hours or days to just minutes,” says Naa Adorkor Yawson, an executive at Zipline in Ghana.

The startup says it has raised $225 million since it was founded, and plans to expand further across Africa, south and southeast Asia and the Americas, with the aim of reaching 700 million people in the next five years.

Remote care

While infrastructure can be poor, the number of mobile internet users in sub-Saharan Africa is growing rapidly. According to GSMA, the mobile industry’s trade body, smartphone connections in the region reached 302 million in 2018. GSMA expects this to rise to nearly 700 million by 2025.

As a result, apps that enable remote access to medical advice and diagnosis are popping up across the continent.

Hello Doctor, a South African app, provides essential healthcare information, access to advice and a call back from a doctor for 55 rand ($3) a month.

Omomi helps pregnant women and mothers in Nigeria monitor their children’s health and chat with doctors on a pay-as-you-go or subscription basis. A one-off consultation costs 200 naira ($0.55), while a monthly subscription to the online platform costs 2,000 naira ($5.50).

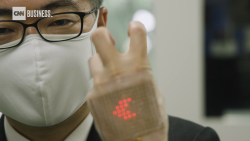

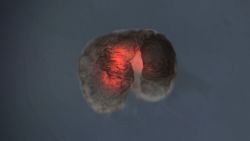

In Uganda, clinical trials are testing an app and device for diagnosing malaria. Matibabu has developed a tool that diagnoses malaria without a blood sample. It clips on a finger, and by shining a red beam of light on the skin it can detect Plasmodium — a malaria-causing parasite — in red blood cells. The results can then be viewed via an app.

Brian Gitta, one of the app’s founders, explains that blood testing for malaria is time consuming and usually requires access to a health clinic. “We do a diagnosis in two minutes versus 15 to 30 minutes for a blood test,” he tells CNN Business, adding that Matibabu has an 80% accuracy rate.

Smart lockers

Long waiting times are often a problem for public clinics. In 2014, following a tuberculosis diagnosis, Neo Hutiri had to spend three hours in a line every other Friday to collect prescription medicine from a clinic.

This experience inspired him to develop Pelebox, a smart locker system that dispenses medicine to patients with chronic illnesses.

When the medication is ready, patients receive an SMS message with a unique code that opens the locker.

“Pelebox enables patients to collect their repeat chronic medication in under 22 seconds instead of waiting for hours in queues at public clinics,” Hutiri tells CNN Business.

He hopes it will reduce the workload for hospital staff and allow them to focus on patients with critical needs. So far, 13 machines are operating in Gauteng, a province in South Africa. Hutiri hopes to scale this up to 50, to reach 1,000 communities over the next five years.