Editor’s Note: Seema Golestaneh is Assistant Professor of Middle East Studies at Cornell University. The opinions expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion at CNN. View more opinion articles on CNN.

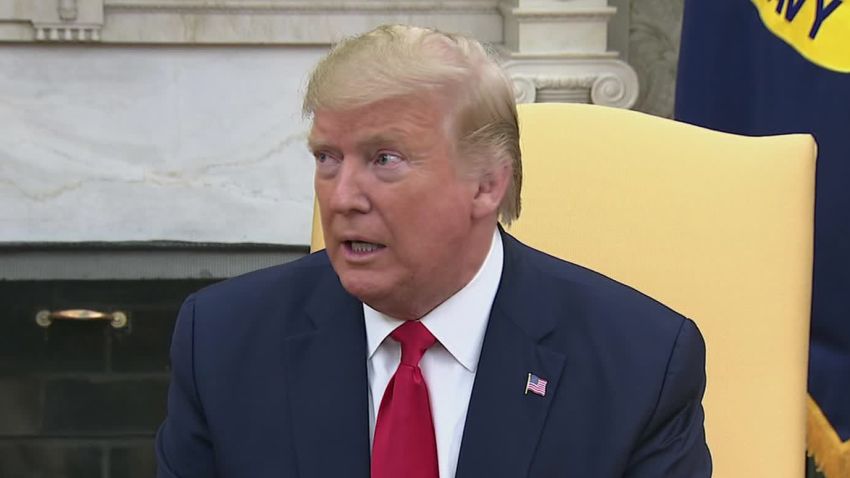

Over the weekend, President Trump twice tweeted out threats to attack sites that are important to “Iranian culture.” Since then, Trump appeared to walk back his comments somewhat, and Secretary of Defense Mark Esper has suggested that the US would make no such attacks, stating that the country would follow “the laws of armed conflict.”

That is a small reassurance: To target sites of cultural heritage is a violation of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, of which the United States is a signatory. Given the President’s tendency to go against precedent and the counsel of his advisers, however, his threat still hangs ominously in the air.

Regardless, it seems strange to me that President Trump, a man not prone to making mention of “capital C” culture, seems to direct his hostility toward cultural heritage sites — places prized by the Iranian people, for whom he has professed support.

Indeed, while the aesthetic and historical significance of these works of art and architecture has been well documented, less discussed is the role of these antiquities in the lives of Iranians. Many of these sites are not sterile tourist destinations, sequestered off by from the bustle of the city and ignored by local denizens, but are woven into the fabric of everyday life.

I am Iranian-American, born in Brooklyn and raised in New York, but like many Americans, have beloved family members who live in the country my parents came from. I have had the good fortune to visit Iran many times and experience its cultural treasures — a historical and aesthetic landscape very different from the one back home.

In the city of Isfahan is the Imam’s Square, the second largest square in the world after Tiananmen, and a UNESCO protected site. Built nearly 400 years ago by the Safavid King Abbas, it houses a bazaar that runs two kilometers long, mosques completely covered in elaborate tile inlays of brilliant blues, yellows, and greens and multiple tea houses.

This is not only a place out-of-towners visit to snap selfies, but one where Isfahanis go to buy shoes and spices, pray in a house of worship and relax. On weekends, families and friends gather for picnics on the green while their children play in the fountains. Young couples stroll the perimeter of the square, ice cream in hand.

The awe-inspiring footbridges of Isfahan, some of which date back to the 7th century, could also be in the line of fire were President Trump to make good on his threats. The River Zayandeh cuts right through the middle of the city and hundreds of thousands of people cross the bridges every day. They are marvels of technical engineering, acting as dams and sluice gates, as well as places to dip your feet in cool water when the river is high.

The acoustics of these snaking and beautiful bridges, many of them comprised of covered arches, are taken full advantage of by locals, as people recite poems and sings songs in the evenings. Reciting poems on the bridges is a pastime that dates back hundreds of years; the only difference now is that the small crowds that gather round are taking videos of the proceedings with their cellphones.

Opinion: What Iran strike means for the US

These are public spaces — everyday spaces — that tie a people to their past. These places and things are not fossilized relics of a bygone era, but allow for a way of life that is uniquely Iranian. The survival of these structures, which have outlasted invasions, wars, and occupations, means that Iranians can interact with works of art and architecture from the past on a daily basis. To destroy these structures is not only to destroy irreplaceable masterworks, but a way of life.

A great number of these actively used cultural heritage sites belong to the religious minorities of Iran. The Vank Cathedral, every inch of its interior painted with stunning murals and portraiture, is the pride of the Armenian-Iranians. The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, standing strong since the 12th century, is the most popular pilgrimage site for Iran’s Jewish community, the largest in the Middle East outside of Israel. And the Zoroastrians of the nation have kept a single flame lit in the stately Behram Fire Temple of Yazd since the year 470 AD.

The United States is a young country and it is perhaps hard to understand the deep affection Iranians hold for these historical places and the role they play in everyday life. We do not have the opportunity here in America to cross medieval bridges on the way to work, to walk through gardens first planted by poets and kings one thousand years ago.

But when Paris’ Notre Dame cathedral caught fire this past spring, we all watched in horror, feeling distraught and powerless, as the flames burned higher. The entire world mourned. Now imagine if someone had threatened such destruction, quickly tweeting out such a missive, without so much as a second thought.

I wish I did not have to explain why the people of Iran would be so distraught if even one of their treasured sites were attacked. I wish we could turn instead to our common humanity to understand the suffering of others. But we live in an era where the unthinkable is possible, and for the first time in a long time irreplaceable works that are the testaments to the best of the human spirit are at risk.

Whether the President understands the blow to Iran that such cultural devastation would inflict is impossible to know. Or maybe he knows that to destroy a people, you must first tear out their heart. Outside of the loss of life, for Iranians but also many others, nothing could be more painful.