As Chief Justice John Roberts presides over the Senate trial of President Donald Trump, he has a highly public perch but little control. He is directing the proceedings but almost certainly will not cast any votes. He is fulfilling his constitutional duty but leave Trump’s fate to the Senate, which has “sole power to try all impeachments.”

In many respects, it represents the polar opposite of his life at the Supreme Court.

These days, Roberts not only holds the center chair of the nine-member court but, since the 2018 retirement of centrist conservative Anthony Kennedy, resides at the middle of the ideological spectrum of the bench. That often puts Roberts in a position as the decider, in a venue where cameras are not allowed and most of the justices’ work occurs behind closed doors.

In the Senate, Roberts has only as much power as senators give him – and with the TV cameras rolling.

In today’s atmosphere of erratic politics, the chief justice could feel some pressure to intervene more substantively, even to determine whether senators hear from witnesses who know about Trump’s dealings with Ukraine. Partisans on both sides might want Roberts to sway the trial their way, even if he sees his job as a simple presiding officer.

On Tuesday, he has mainly been reciting procedural rules, keeping the clock and reading aloud vote tallies. He has not been challenged to intervene beyond the administrative tasks at hand.

Yet Roberts is surely bracing for any scenario. Heading into the Senate trial, he would likely have anticipated all manner of possible disruption, by senators, the House managers and perhaps even Trump, with whom he has tangled in the past.

The chief justice has long been known for his extensive preparation and an ability to foresee what’s ahead that some colleagues have likened to three-dimensional chess.

When he was a lawyer arguing in courts across the country, he showed up a day early to scope out the courtroom and talk to the bailiff. He practiced his arguments relentlessly, from the pronunciation of difficult names to critical segues to main points, irrespective of the question a judge asked.

Roberts already been poring over Senate rules and reading through materials on the two prior impeachment trials, in 1999 of President Bill Clinton and in 1868 of President Andrew Johnson.

When Chief Justice William Rehnquist oversaw the Clinton case, he made sure his role was ministerial, not substantive.

Rehnquist, who was a mentor to Roberts, famously took a page from a Gilbert and Sullivan character and said, “I did nothing in particular, and did it very well.”

Roberts is more personally cautious and reserved than was Rehnquist, who died in 2005. Rehnquist famously wore a robe with gold stripes – also a Gilbert and Sullivan reference. Roberts is not likely to do anything that would unnecessarily call attention to himself, beyond his constitutional duty.

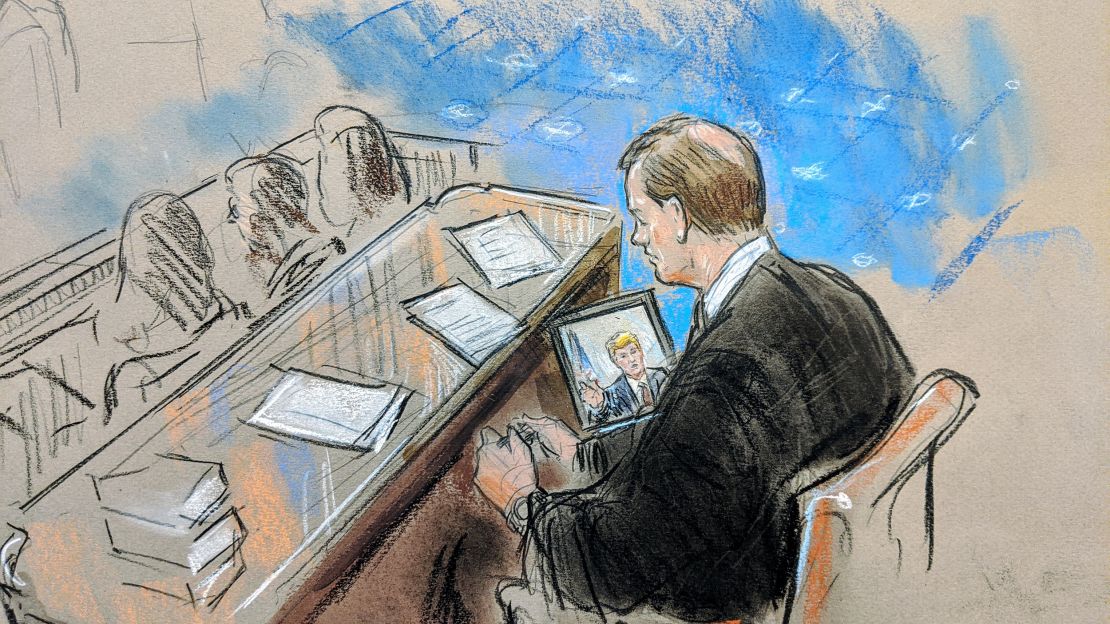

On Tuesday, he sat with black-rimmed glasses on the tip of his nose, watching debate attentively and taking notes. Before him were three legal books to his left and a glass of water on his right. Senate parliamentarian Elizabeth MacDonough regularly whispered guidance as he responded to activities on the floor.

The chief justice, who turns 65 on January 27, has carried the mantle of public expectations before – and often dashed those expectations. He has disappointed conservatives who wanted the 2005 appointee of President George W. Bush to vote consistently for their side. Roberts has equally confounded liberals seeking regular replays of his 2012 decisive vote (with the justices on the left) to uphold the Barack Obama-sponsored Affordable Care Act.

Yet Roberts has in recent years has tried in public speeches to rope off himself and the federal judiciary from the politics of the day.

In November 2018, he implicitly admonished Trump for deriding a US district court judge who had ruled against his administration in an immigration case as an “Obama judge.” Roberts countered, “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

Trump fired back on Twitter: “Sorry Chief Justice Roberts, but you do indeed have ‘Obama judges,’ and they have a much different point of view than the people who are charged with the safety of our country.”

A job directed by the Constitution

The Constitution requires Roberts’ presence. It says: “The Senate shall have the sole power to try all impeachments” and that “When the President of the United states is tried, the Chief justice shall preside.”

As happened with Rehnquist in 1999, Roberts will have office quarters in the Capitol’s ceremonial President’s Room, known for its rich Italian frescoes, intricate glass chandelier and vibrant floor tiles.

Roberts, who will simultaneously continue to vote and write opinions on high court cases, is being assisted by Jeffrey Minear, a longtime colleague who holds the title of counselor to the chief justice. Thirty years ago, Roberts and Minear worked together in the office of the US Solicitor General, the government’s top lawyer before the court.

When Roberts served in that office, from 1989-1993, he was principal deputy to Solicitor General Ken Starr, now on the defense team representing President Trump.

During his tenure in the solicitor general’s office and then in private practice, Roberts argued 39 times before the Supreme Court and was considered the gold standard by justices across the ideological spectrum. He was able to synthesize complicated facts and legal issues into an accessible, conversational argument.

But it took serious rehearsing and constant efforts to calm his nerves. He was so skilled at his presentations that colleagues were sometimes surprised to see his hands shake before he stepped to the lectern.

Roberts left nothing to chance. He would write at the top of his materials the opening words with which every lawyer who appears in court begins: “Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court.” Roberts wanted it at hand, just in case he froze.

A scripted affair

This impeachment trial will be both a more scripted affair for Roberts – he will work closely with the Senate parliamentarian – yet one controlled by the predilections of others.

Time and again in 1999, then Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, a Republican from Mississippi, laid out how the hours would proceed, then turned the session over to Rehnquist to carry out the schedule.

The Senate’s impeachment trial rules, which have evolved over time and most recently date to 1986, dictate that the chief justice “may rule on all questions of evidence including but not limited to, questions of relevancy, materiality, and redundancy.”

His decisions, however, could be overturned by a majority vote (51 votes) of the Senate.

Back in 1999, Rehnquist ruled on no evidentiary questions, so there was never a showdown with senators.

Some commentators have speculated that Roberts could break a tie vote of senators, perhaps on issues related to witnesses. But impeachment scholars such as University of North Carolina law professor Michael Gerhardt, a CNN contributor, do not believe Roberts would be so empowered.

“He can make a ruling on procedural and evidentiary matters, but every ruling he makes may be appealed to the entire Senate, which may overrule him,” Gerhardt said. “The Senate, not Roberts, has all the power, and that means a majority of the Senate controls this trial.”

Rehnquist never claimed such voting power, but in the Senate trial of President Johnson, Chief Justice Salmon Chase broke senators’ tie votes. Chase, it should be emphasized, held presidential ambitions and claimed a large and controversial role in that 1868 trial.a

Both Johnson and Clinton were acquitted. Under the Constitution, a president can be removed from office only with a two-thirds majority, which today would be 67 votes.

To be sure, when the vice president presides over the Senate, he is able to break a tie when senators are evenly split. But the Constitution’s Article I specifically gives the vice president that power. There is no comparable provision for the chief justice in an impeachment situation.

During the Clinton trial, senators wrangled over witnesses but against a far different backdrop. The US House had impeached Clinton only after receiving extensive testimony compiled by then-independent counsel Ken Starr. Senators were not weighing whether to hear from new witnesses but rather who among the multitude who had testified should be called to the Senate floor.

The Senate compromise in 1999 to allow the videotaped testimony of three witnesses, including former White House intern Monica Lewinsky, with whom Clinton had had a sexual liaison and who became the focus of the Starr report.

The lack of live witnesses further diminished Rehnquist’s duties. “I have been introduced to the ways of the Senate in a big way,” he wrote to former Senator Mark Hatfield, R-Oregon, as the trial was underway. “Since there have been no live witnesses, there has been very little for the presiding officer to do, but it is interesting to see the Senate at work.”

Under the current Senate rules, “if a Senator wishes a question to be put to a witness, or a manager, to counsel of the person impeached … it shall be reduced to writing, and put by the Presiding Officer.”

While he had no questions to address to witnesses in the Senate, he spent hours reading questions to House managers (making the case against Clinton) and the President’s legal team. Rehnquist read aloud the queries, word for word, in a dry clerk-like rendition.

Whatever his thoughts on the validity of any questions, Rehnquist kept them to himself.

It was not until the end of the trial that he expressed any sense of his overall sentiment. “I underwent the sort of culture shock,” he told senators, “that naturally occurs when one moves from the very structured environment of the Supreme Court to what I shall call, for want of a better phrase, the more freeform environment of the Senate.”

CNN’s Manu Raju contributed to this report.