He’s the billionaire scion of Thailand’s biggest auto parts manufacturer who could have led a quiet, comfortable life in the upper echelons of Thai society.

Instead, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit is fighting to save his country’s democracy, and in doing so has put himself in the crosshairs of the military-led government.

Last week, Future Forward, the pro-democracy political party Thanathorn founded in 2018, and which came third in Thailand’s election last year with 6.3 million votes, was banned by a Thai court for violating election laws.

Angered by what they saw as political interference, students are leading pro-democracy rallies around the country calling for former general-turned-prime minister, Prayut Chan-o-cha, to step down, six years after he seized power in a coup in 2014.

In just two years, Future Forward and its leaders have been hit with more than 20 legal cases, including criminal charges that could result in jail time. Thanathorn denies wrongdoing and says the cases are politically motivated.

The party’s platform of democratic and military reform, and decentralized power, would require deep structural changes to the Thai political system.

“It’s clear that we confront the rule of the junta very directly,” Thanathorn said. “All these things are quite provocative, it’s quite radical when it comes to Thai politics.”

While Thanathorn’s ambitions to bring about reform from within parliament are scuppered for now, he is poised to lead what he sees as a burgeoning democratic movement.

His life’s mission is, he says, to “break the chains” of a system that is preventing Thailand from progressing, and put power in the hands of the people.

It’s a mission that could soon see him jailed.

“It is the cost of the struggle, it is the cost to bring democracy back to Thailand and it is the cost I’m willing to pay,” he says.

The billionaire commoner

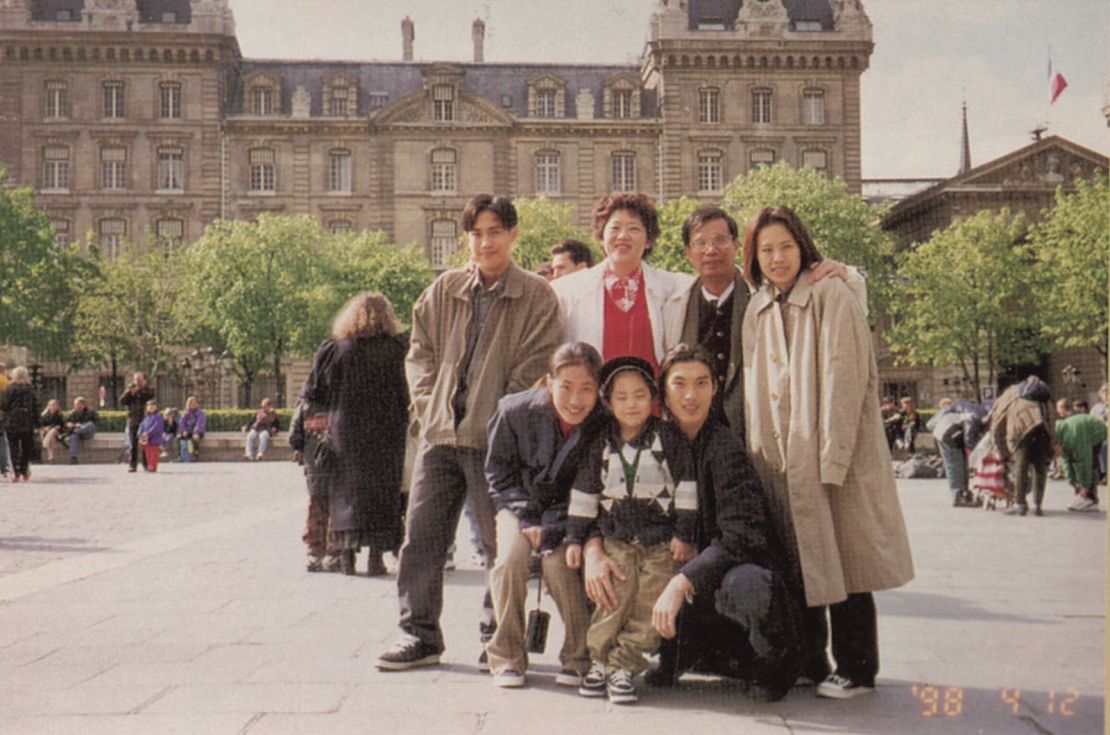

Thanathorn’s grandparents moved to Thailand as poor Chinese immigrants about 70 years ago, and he remembers his parents working day and night to feed the family.

His father had two jobs, selling noodles during the day and fixing motorcycle seats at night, while his mother sold fish maw soup in China Town. Their fortunes started to change when a representative from Yamaha asked Thanathorn’s father to produce motorbike seats for them.

The business, which he started with his brother, started to grow, as big brands including Honda, Suzuki, and Kawazaki, placed orders. The family turned Thai Summit Group into a multi-billion dollar company.

Thanathorn says his parents kept him grounded by making him get part-time jobs during the summer holidays.

“I would do the dishwashing in the restaurants, (work as) the bell boy in hotels, I do the loading and unloading in the warehouse,” he said.

In his twenties, Thanathorn studied mechanical engineering at Bangkok’s prestigious Thammasat University.

The university has a long history of political activism.

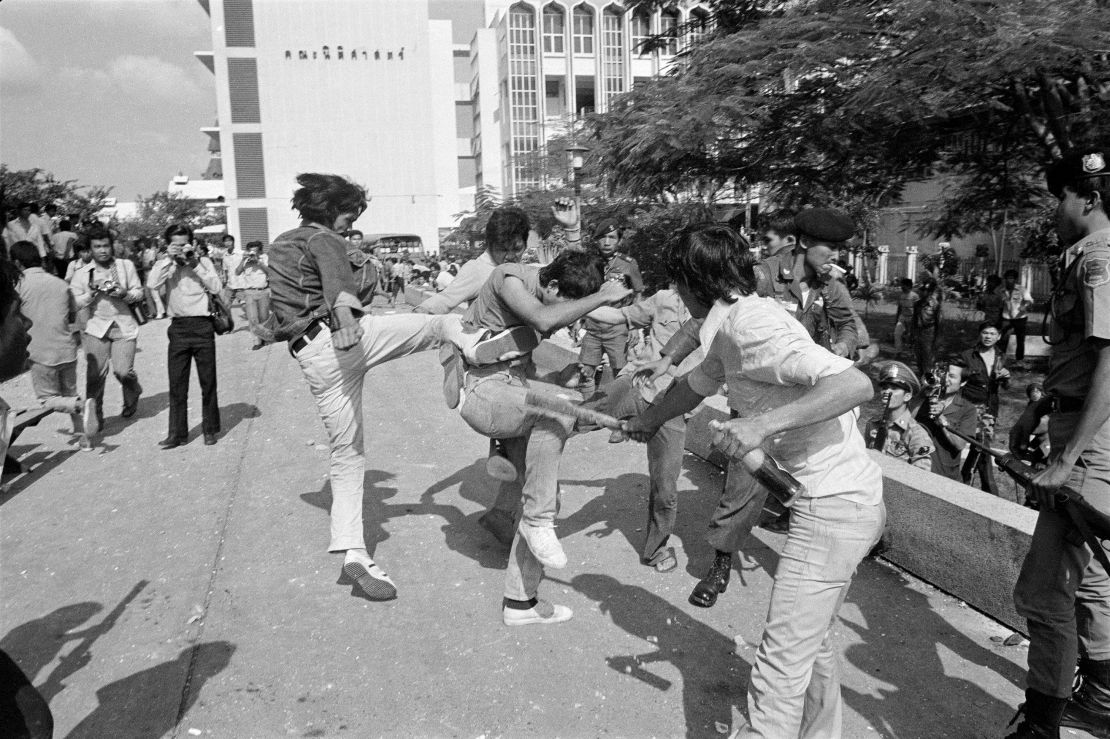

One of its campuses was the site of the October 6, 1976 massacre, when state security and far-right paramilitary forces opened fire on leftist students protesting the return of a former military dictator. Students were shot, beaten and murdered. The official death toll is 46, but survivors claim it was more than 100.

Thanathorn immersed himself in the student movement.

As president of Thammasat student union, and later the vice secretary general of the Student Federation of Thailand, he became an advocate for land rights and the poor and joined student protests. “That’s how I learned the struggle of the people. That’s where I learned the structural cleavage of Thai society,” he said.

After graduating, he intended to continue his social justice work with a career at the United Nations. But soon after beginning a deployment as a development worker in Algeria, his father died.

He said his mother asked him to return home and helm the family business. He was 23 years old.

Despite his age and lack of corporate experience, Thanathorn proved to be the right choice.

In the decade or so that he served as Thai Summit Group’s vice president, the company’s revenue grew from 16 billion baht ($500 million) in 2001 to 80 billion baht ($2.5 billion) in 2017. It now has a presence in seven countries, including the US, and employs more than 16,000 globally.

He also served on the board of Thai media company Matichon, known for its liberal leaning daily papers and in-depth political analysis and insight articles that focus on political and social issues.

Rinse and repeat

Thanathorn was in his early thirties when Thailand experienced one of the bloodiest episodes in its recent history.

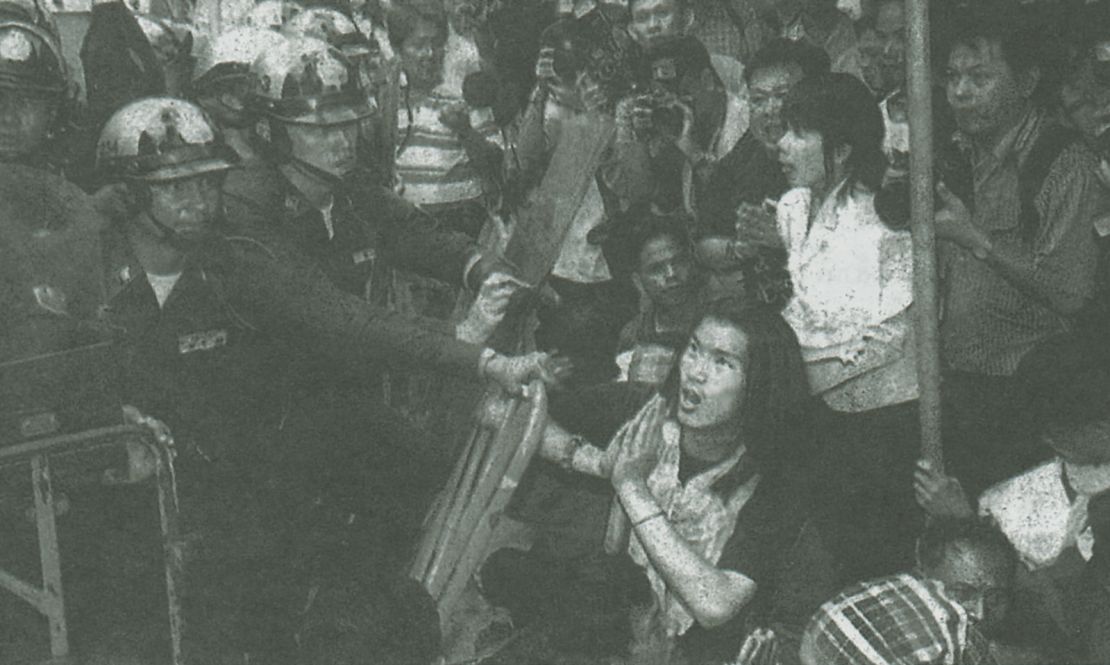

It was 2010. For months, Thailand had been rocked by protests by the Red Shirts – supporters of the popular leader Thaksin Shinawatra, who had been deposed in coup in 2006. Protesters occupied Bangkok city center and demanded Democrat Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva step down. He ended the standoff by authorizing the military to use live ammunition.

More than 90 people died and hundreds were injured in the street battles that followed.

With the origins of what would become the Future Forward Party germinating, Thailand’s political landscape became no less complicated. In 2014 another coup rocked the country, and Prayut Chan-o-cha installed himself prime minister.

Shortly after taking over, Prayut banned all political campaigning including political gatherings of more than five people, hundreds of activists were arrested and charged under draconian laws such as sedition or lese majeste – which prohibits criticism of the royal family – and a Computer Crimes Act restricted online expression and increases surveillance and censorship.

“Over the past five years, people who stood up and spoke up against the junta, they are charged, they were put into jail, their families were threatened,” Thanathorn said. “They use the threat of law suits against the people who speak up.”

Thanathorn decided he couldn’t sit on the sidelines any longer.

In early 2018, Thanathorn and his friend, Thammasat University law professor Piyabutr Saengkanokkul, decided to form a new political party. The Future Forward Party was born.

‘We love daddy’

Entering politics put Thanathorn under scrutiny.

For one, his uncle had been part of the establishment he was railing against. From 2002 to 2004, Suriya Jungrungreangkit had been Transport Minister under Thaksin, and was a leader of Palang Pracharat – the military-backed party that nominated coup leader Prayut for Prime Minister. He’s currently serving as Thailand’s Minister of Industry.

And, as one of the 1% in Thailand, questions were asked over how he could really connect with the issues of the normal people he claims to advocate for.

Despite his wealth, Thanathorn doesn’t consider himself to be privileged. “It’s not about wealth, it’s about connections with people who control Thailand. It’s not about how much money you have,” he said.

The public didn’t seem to mind. Young voters flocked to the telegenic, charismatic new leader, taking selfies and shouting “fah rak phor”– a phrase from a popular Thai drama that translates to “we love daddy.”

“When Thanathorn offered himself as an alternative, he was full of ambitions, interests and political excitement,” said Theerachai Rawiwat, 21, a Thammasat university student. “(Future Forward) could represent the new generation better than other political parties.”

Future Forward’s policies included changing the 2017 military-drafted constitution, which allows for an unelected prime minister and a third of the legislature to be appointed by the military.

“Power has been centralized to the hands of the junta,” Thanathorn said. “You make a totalitarian regime become permanent under this constitution.”

His party also wanted to cut the defense budget, increase government transparency, strengthen democratic institutions, uphold human rights and break up business monopolies.

“This is a kind of party Thai politics has not seen before in the past. It’s radical, welfare-minded and pro-business,” Thitinan Pongsudhirak, director of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University told CNN last year as Thais prepared to vote for the first time in eight years.

“It’s a turning point and overdue because Thai politics has for more than the past three decades been dominated by the same old faces of politicians.”

But the same old faces were returned to power in an election criticized as “not free and fair.”

Prayut retained the leadership under election rules that allow both houses of Parliament – including the military-backed Senate – to choose the prime minister.

Still, Future Forward’s electoral success was unheard of – none of its 81 members of parliament had held elected office before. They formed part of the pro-democracy bloc that included the second biggest party, the Thaksin-aligned Pheu Thai.

The take down

Right from its founding, Future Forward Party and its executives were hit with dozens of legal cases, ranging from sedition, computer crimes and undermining the monarchy. It was even accused of having links with shadowy secret society, the Illuminati.

In November 2019, Thanathorn was disqualified from being a lawmaker after the Constitutional Court ruled he illegally held shares in a media company while running as a candidate.

Thanathorn said he had transferred his shares in V-Luck media to his mother before the election was announced on January 23, and the company had ceased operations. The court said there was no evidence that transfer was made.

And in February the Constitutional Court dissolved the party and banned its leaders from politics for 10 years, ruling that they accepted an illegal 191 million baht loan (about $6 million) from Thanathorn. The court ruled the money was a party donation and therefore exceeded the legal limit.

Thanathorn said the loan was legitimate and the party would repay it. “The law allows us to give the loan, lots of other political parties also get loans,” he said.

Critics say Thanathorn is a corrupt billionaire who violated election law. His supporters say the charges were political.

“We did nothing wrong, we insist that all these cases are politically motivated,” Thanathorn said.

The move to disband a democratically-elected party hit a nerve.

A statement from the US Embassy in Thailand said the decision “risks disenfranchising those voters and raises questions about their representation within Thailand’s electoral system.”

Rights group Amnesty International said the ruling “illustrates how the authorities use judicial processes to intimidate, harass and target political opposition.”

The Future Forward Party’s remaining lawmakers have now formed a new party in order to retain their seats. The 11 seats held by the now banned party executives, including Thanathorn, will be left vacant.

The Election Commission, which brought the complaint, could take criminal action against the Future Forward executives.

If that comes to pass, Thanathorn could face five years in prison, and the other party leaders three years.

He says he is prepared to go to prison to fight for the future of his four children, aged between 12 years and just 15 months old.

“If I go to jail I wish someone would tell them that I go to jail because I’m fighting for democracy, I’m fighting for the next generation,” he said.

Faced with the threat of prison, other political leaders have chosen to flee the country. Both Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra – the sibling former prime ministers – fled Thailand as criminal trials were held against them.

For Thanathorn, leaving the country is not an option, he said. “I cannot flee, if I flee the whole movement might collapse.”

The battleground for ideas

Despite his political and legal woes, Thanathorn says he’s excited about Thailand’s democracy movement.

In December, thousands of people rallied in Bangkok in what local media called the biggest protest since before the 2014 coup, in support of Future Forward. Protesters gave the three-fingered salute from the “Hunger Games” franchise that has become synonymous with Thailand’s democratic struggle.

And more recent campaigns led by university students have sprung up all over the country, with groups holding flash-mob rallies that were a hallmark of the recent Hong Kong anti-government protests.

“We have all the opportunities to make general structural change come true. This has never happened before at least in my 40 years of life,” he said. “We have the chance to end the military intervention into politics once and for all.”

Thanathorn says he’ll lead what has now become the Future Forward Movement and “continue to campaign for progress and liberal ideas across the country.”

“The most crucial battle is not in the parliament, it’s not in the streets – the most crucial battle is the war of ideas,” Thanathorn said.

Asked whether he will join the students and lead them in the streets, Thanathorn said he would – if asked.

Critics, however, are concerned that the anti-government protests could prompt a military response. Army chief Apirat Kongsompong has issued a thinly veiled warning. “I’ll never let anyone burn the country,” he said, according to the Bangkok Post.

Thanathorn said “no blood should be spilled for the fight for democracy” but acknowledged that the movement is now bigger than him or his former party.

“People out there who are still campaigning, they are not campaigning about me or Future Forward – they are campaigning about democracy, they are campaigning about justice,” he said. “The issue has gone far beyond me.”

This, Thanathorn says, “is the most exciting time in the history of Thailand.”