On a blue-sky day in May, as the coronavirus raged across the world, the Chinese flag was raised on a remote nation with a total population of 116,000, thousands of miles from Beijing.

The opening of a Chinese embassy on Kiribati, a nation of 33 atolls and reef islands in the central Pacific, might have seemed strange – particularly during a pandemic. Just three other countries have embassies in the island state: Australia, New Zealand and Cuba.

Yet Kiribati is the site of growing geopolitical competition.

Last September, it switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. China considers the self-governed island of Taiwan a breakaway province and has poached seven of its diplomatic allies since 2016.

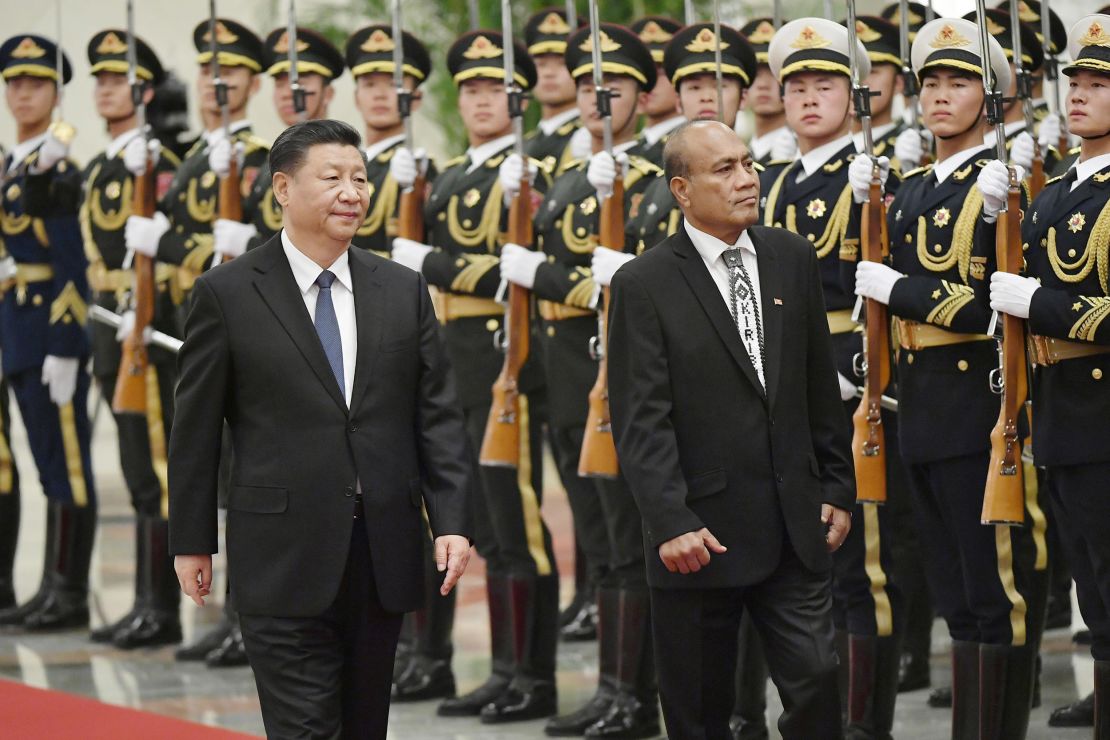

And this week, Kiribati’s pro-Beijing President Taneti Maamau – who oversaw the country’s diplomatic switch – won a closely watched election after campaigning for closer ties with China, defeating an opposition rival who was sympathetic to Taiwan.

Kiribati is the latest example of Beijing’s growing influence in the Pacific, which consists of a string of resource-rich islands that control vital waterways between Asia and America.

The picturesque islands have long been aligned with the US, which has a large military presence, and allies such as Australia, the region’s largest donor and security partner. But in recent years, many have forged closer ties with China due to Beijing’s diplomatic and economic outreach – creating a fault line for geopolitical tensions.

Now, as Canberra and Beijing pour aid into the region, the possibility of a travel bubble between the Pacific Islands and Australia has given the rivalry a new dimension.

Deepening reach

In 2006, then-Premier Wen Jiabao became the most senior Chinese official to visit the Pacific Islands. He pledged 3 billion yuan ($424 million) in concessional loans to invest in resource development, agriculture, fisheries and other key industries, signposting Beijing’s interest in the region.

Today, Beijing is its second-largest donor – after only Australia, according to data compiled by the Lowy Institute, an Australian think tank.

For the Pacific Islands, which have a combined GDP of about $33.77 billion – less than 1% of China’s total GDP – China has been a crucial partner during the pandemic.

Chinese health experts have given advice on how to fight the coronavirus over video conferences with their counterparts in the 10 Pacific Island countries sharing diplomatic relations with Beijing.

In March, China announced the donation of $1.9 million in cash and medical supplies to the countries to help them combat Covid-19. It has also sent medical supplies, protective gear and test kits, according to statements from Chinese embassies in the region.

Chinese medical teams are on the ground in nations including Samoa, helping local health authorities draft guidelines on how to control the coronavirus. In Fiji, specialized military vehicles have been provided.

According to the World Health Organization, the Pacific has reported 312 cases and 7 deaths, the majority of which are in the US territory of Guam.

The islands have so far largely warded off the coronavirus thanks to their remoteness and early lockdown measures. But local communities could face devastating consequences if the virus was to be hit, because of inadequate health care and lack of testing capacity, experts have warned.

“China’s engagement in the Pacific today has been one driven by opportunism, they’re trying to gain as much influence as they can,” said Jonathan Pryke, director of the Pacific island program at the Lowy Institute.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry denies this, saying China’s assistance to Pacific Island countries is “genuine” and does not have “any political attachment.”

But stronger ties can come in handy in times of need.

In May, when China was facing a global backlash over its early handling of the coronavirus outbreak, it turned to the Pacific for support. Days before the World Health Assembly meeting in May, ministers from 10 Pacific Island nations joined a video conference on Covid-19 convened by China.

The meeting ended with a glowing affirmation of China’s coronavirus response.

“This is what the Chinese government needed,” said Denghua Zhang, from the Australian National University in Canberra.

In joint press release after the event, the Pacific Island nations commended China for its “open, transparent and responsible approach in adopting timely and robust response measures and sharing its containment experience.”

The Trump administration has repeatedly blamed China for the pandemic, while Canberra has infuriated Beijing with its call for an independent inquiry into the origins of the virus.

Australia steps in

China’s coronavirus assistance to the Pacific, however, pales in comparison to the financial support provided by Australia. Last month, Canberra said it was spending 100 million Australian dollars ($69 million) to provide “quick financial support” to 10 countries in the region, with the money redirected from its existing aid programs.

Australia has also recently announced that it will beam popular domestic television shows like “Neighbours” and “Masterchef” into seven Pacific Island countries – a move widely seen as a soft power push to counter China’s rising influence.

“The Australian government has clearly acknowledged that there can’t be any room for vacuum creation, (be it) the hard power, soft power, the aid front, or the medical front,” Pryke said.

“They can’t step back from any vacuum for fear that China might fill it.”

This was on Australia’s radar before the pandemic. After coming into office in 2018, Prime Minister Scott Morrison launched his “Pacific Step Up” initiative, which includes increased foreign aid and the establishment of a $1.5 billion infrastructure fund for the region.

Travel bubble

One way the pandemic could affect the geopolitical rivalries in the Pacific is the selective easing of travel restrictions among countries.

As Australia and New Zealand bring the coronavirus under control, their politicians are talking about opening up borders between each other, creating a travel corridor – or “travel bubble” – between the two nations.

Both countries had successfully flattened their coronavirus curves by late April, though Australia is now facing a spike in cases in the state of Victoria.

Pacific Island nations including Fiji, Samoa and the Solomon Islands have requested to join the plan.

So far, there has been no publicly reported plan between the Pacific Islands and China for a similar travel bubble. At the moment, China seems to be focusing on its neighboring borders – its southern province of Guangdong has been in discussion with Hong Kong and Macau for a travel bubble.

The coronavirus lockdowns have put huge pressure on the tourism-dependent economies of the Pacific nations, and Australia and New Zealand are the main source of tourists there. In 2018, the two countries contributed more than 1 million foreign arrivals into the Pacific region, accounting for 51% of tourist arrivals, according to a report from the South Pacific Tourism Organization. In comparison, 124,939 Chinese tourists visited the Pacific Islands in 2018, a 10.9% decrease from the previous year.

Some Australian politicians are also eager to see a trans-Pacific bubble.

Dave Sharma, an MP for the governing Liberal party, wrote in The Australian newspaper last month that the inclusion would help Canberra’s Pacific neighbors economically, and ensure that “they continue to see Australia as their partner of first choice.”

“Strategic competition in the Pacific is alive and well, with China and other countries seeking to play a greater role. It is important our influence and footprint in our near neighborhood is visible,” he wrote.

While geopolitics is not the primary motivator for a travel bubble – rather, the key driver is the urge to get economies back on track, Pryke said – the lifting of travel restrictions between Australia and the Pacific Islands would secure some geopolitical gains for Canberra and Wellington.

“In a way, Australia and New Zealand would become gatekeepers for access into the Pacific whilst the pandemic is continuing around the world. So that would of course give Australia and New Zealand further geopolitical advantages,” he said.