In case this was on your 2020 list of worries, the Earth’s magnetic field is not about to reverse itself.

Strange behavior in the South Atlantic magnetic field can be traced back as far as 11 million years ago, and it’s unlikely to be linked to any impending reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field, researchers have found.

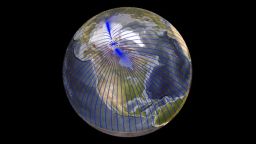

Earth’s magnetic poles, which serve as the foundation of our navigation, are actively moving. The magnetic field reverses its polarity every several hundred thousand years, where the magnetic North Pole resides at the geographic South Pole. The last reversal took place 770,000 years ago, but if a reversal happened during our lifetime, it could impact navigation, satellites and communications.

The perplexing behavior in the South Atlantic region causes technical disturbances in satellites and spacecraft orbiting Earth, which has left experts puzzled.

The area is one of debate between scientists, some of whom question where it comes from, and if it could signal the total weakening of the field, and even an upcoming pole reversal.

The Earth’s magnetic field protects our atmosphere from solar wind, which is a stream of charged particles coming from the sun. The geomagnetic field is not stable in strength and direction, and does have the ability to flip or reverse itself.

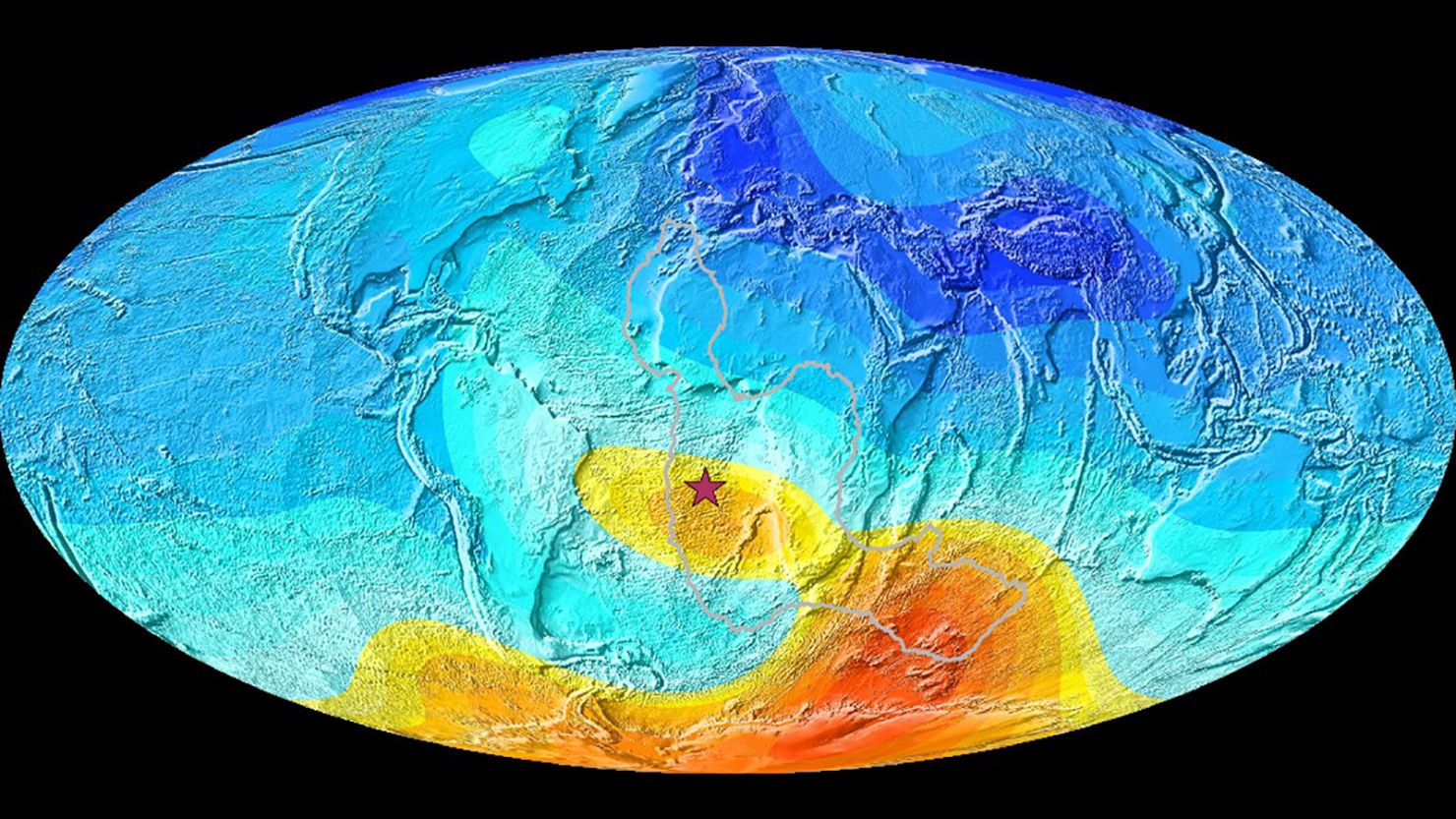

The South Atlantic Anomaly is an area stretching from Africa to South America where the Earth’s magnetic field is gradually weakening.

Here’s the good news: In research published Monday, scientists from the University of Liverpool said they have proof that today’s South Atlantic Anomaly is a recurring feature, and is unlikely to be linked to any impending reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field.

Researchers analyzed igneous rocks from Saint Helena island, a tiny volcanic island located right in the middle of the South Atlantic and lies in the South Atlantic Anomaly.

Geomagnetic records from the rocks, which covered 34 volcanic eruptions from the area between 8 and 11 million years ago, revealed that the magnetic field for Saint Helena often pointed far from the North Pole – just as it does now.

Largely generated by an ocean of superheated liquid iron in Earth’s core, the magnetic field creates electrical currents, which in turn generate our changing electromagnetic field. The field, which is not static, varies in both strength and direction, according to the European Space Agency.

“Our study provides the first long-term analysis of the magnetic field in this region dating back millions of years,” said lead author Yael Engbers, a doctoral student at the University of Liverpool, in a statement. “It reveals that the anomaly in the magnetic field in the South Atlantic is not a one-off; similar anomalies existed eight to 11 million years ago.”

“This is the first time that the irregular behaviour of the geomagnetic field in the South Atlantic region has been shown on such a long timescale,” Engbers said in the statement. “It suggests that the South Atlantic Anomaly is a recurring feature and probably not a sign of an impending reversal.

“It also supports earlier studies that hint towards a link between the South Atlantic Anomaly and anomalous seismic features in the lowermost mantle and the outer core,” Engbers added. “This brings us closer to linking behaviour of the geomagnetic field directly to features of the Earth’s interior.”

CNN’s Ashley Strickland contributed to this report.