Shortly before Joe Vardon started covering last year’s NBA playoffs, the sports journalist took his family to Walt Disney World.

Now, more than a year later, Vardon is back in Orlando, Florida — staying at the same Disney (DIS) hotel, in fact — but it’s a whole new world. Everyone is wearing masks. There are temperature checks at the entrances. And oh yes, there’s a deadly pandemic tearing across Florida, one of the country’s coronavirus hotspots.

Vardon, a senior writer for The Athletic, the subscription-based sports website, arrived on July 12 to cover the end of the NBA season, which was suspended earlier this year after a player tested positive for coronavirus. Yet, while Vardon is inside Disney World, he can’t go to the theme park — now open to tourists — even if he wanted to. Once he arrived, he was required to quarantine inside his hotel room for a week.

“The rooms are meant for you to get a comfortable night’s sleep and then go to the [theme] park,” Vardon told CNN Business. “They are not built to spend seven full days in them.”

This is life for a reporter inside the “NBA Bubble,” the quarantine zone inside Disney World designed to keep NBA players and staff from getting sick during what remains of the season and the following playoffs. The bubble houses 20 reporters, 22 teams and will last through October — a massive undertaking that reportedly cost the league more than $150 million.

The campus, with its multiple hotels and complexes such as Disney’s ESPN Wide World of Sports, is like a chapter out of a dystopian novel. Players, staff, and reporters like Vardon are under the watchful eye of the NBA, which has instituted firm rules to keep everyone safe. That includes daily testing and even wearing proximity alarms to make sure you are maintaining social distance.

For the NBA reporters on the inside, the bubble comes with challenges both professional and emotional. They are isolated from family and friends for months, every day feels the same, and let’s not forget the well documented lackluster food.

Yet, the bubble also offers reporters an opportunity to be part of a historic moment — one that comes at a time when the world desperately needs a win.

“There’s a ‘Groundhog Day’ element to it”

NBA players inside the bubble have had their fair share of fun fishing and shotgunning beers, much of which is documented in a Twitter account aptly called “NBA Bubble Life.”

For reporters on the ground, however, life is much different.

Sports Illustrated’s Chris Mannix typically works from about 6:30 a.m. to midnight. His day starts with a workout and a coronavirus test. Then he does TV hits from his hotel room until back-to-back practices or scrimmages begin. Then Mannix writes up the day’s events and goes to bed. Next morning, he does it all over again.

“There’s a ‘Groundhog Day’ element to it,” Mannix, who arrived on July 12, told CNN Business. “It’s like rise, wash, repeat, like every single day. There’s not a lot of differences in each day. It’s just going to different practices or different games, but your days start early, and they end late.”

News outlets shell out about $550 a day for each reporter they send to the bubble, which covers the hotel, food and transportation. The league also allows outlets to swap out reporters. Mannix said he might trade places with a colleague from Sports Illustrated in early September before the season wraps up.

Despite having different restrictions than reporters who are closer to the players, announcers calling the games in the bubble also face a unique set of challenges in the age of coronavirus.

Kevin Harlan, a longtime NBA announcer for Turner Sports, told CNN Business that the league and Turner are “doing everything they can to make this sound like a regular broadcast,” but it’s hard since there won’t be any fans in attendance. (Turner and CNN share a parent company in WarnerMedia)

“The crowd is like an orchestra for a broadcaster,” Harlan said. “You play off a lot of its emotion and noise… and that’s going to be gone.”

Harlan isn’t worried, however. He’s had a lot of experience announcing games without fans as the voice of the NBA 2K video game series.

“I’m in a closet at home with a headset on and no crowd noise, watching clips that they send me and broadcasting those clips,” he said. “So I don’t hear any crowd noise anyway. I’m used to it.”

“A bootlegger that can bring in Dominos”

Disney World is known for its world-class restaurants and bars. But the food and drink options inside the NBA bubble are less than magical.

Vardon admits that his complaints may seem “petty,” but the lack of access to a bar stood out to him. He did bring his own stash of booze to enjoy in his room, however.

Mannix said he wished he had brought more of his own food into the bubble.

“I’m the world’s pickiest eater, so most of the stuff they have at the cafeteria I’m not all that into,” Mannix said. “If there was a bootlegger that can bring in Domino’s, I would probably pay a premium for that at this point.”

Reporting on health problems during a pandemic also poses unprecedented challenges for sports journalists.

Covering the NBA usually means breaking news about broken ankles and torn ligaments, but reporting about an NBA star contracting Covid-19 involve ethical questions. Coronavirus is not only a deadly disease that prevents an athlete from playing, it’s also contagious one that could harm others in the bubble.

Stephanie Ready, a sideline reporter for Turner Sports, understands the challenges of reporting on player’s health during a global health crisis. But since many sports journalists are already well-versed in covering injuries, Ready said that they usually “understand legally what you can and cannot say.”

“This is a disease that’s affecting the entire world,” Ready told CNN Business. “I think that people at home want to know that the athletes they look up to are going through the same things that they’re going through. I think you have to keep it as even-keeled as you can and tell the story factually.”

“It’s really almost like an NBA writer’s fantasy camp”

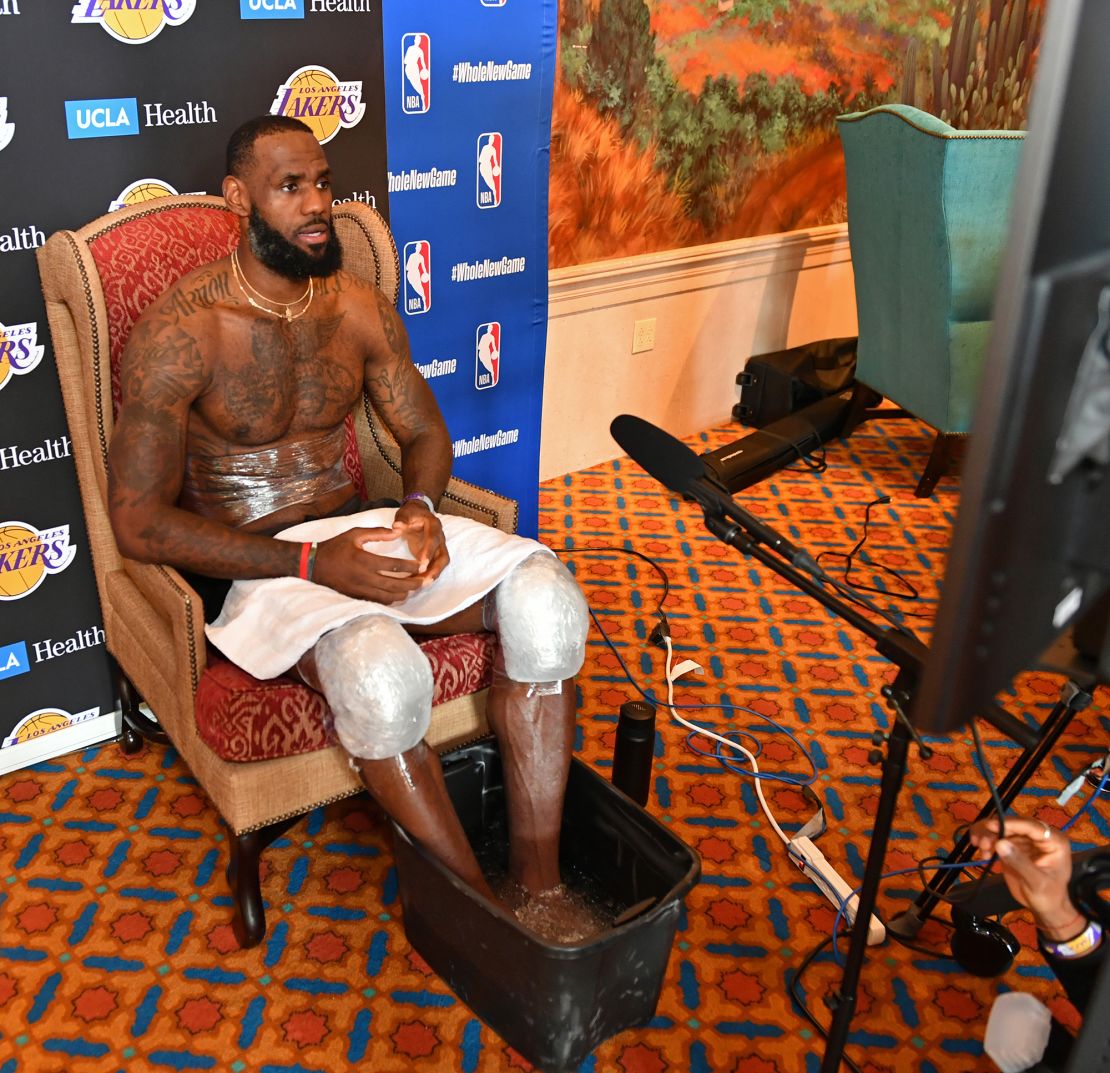

At the resort, reporters are kept mostly separated from players, coaches and other team staff. But while they can’t go roaming the property for scoops, they have had a great deal of access to the teams since arriving in early July.

“You can go from Toronto’s practice to Indiana’s practice to Boston’s practice to Portland’s practice, and even though doing one-on-one interviews requires you to have some social distance between you and the player, you’re still able to get them,” Mannix said. “It’s really almost like an NBA writer’s fantasy camp.”

Living inside the bubble means players, staff and journalists are living in arguably one of the safest places in the country. Right outside the bubble is a different story.

At the time of publication, there have been roughly 4.5 million cases of Covid-19 in the US with more than 460,000 cases in Florida alone.

“It’s not only the happiest place on earth, it’s the safest place on earth,” Lisa Salters, ESPN’s sideline reporter, told CNN Business about the bubble.

Marc J. Spears, a senior NBA writer for ESPN’s The Undefeated, agrees.

“I’m getting tested every day… I have to have it done in the morning, or I can’t access the games or the practices,” Spears told CNN Business. “They enforce wearing a mask. I can’t have anybody in my room because of social distancing. They’re cleaning up stuff all the time. Where else in America is safer than being here?”

“A real piece of American history”

So why would a reporter brave the bubble and leave their lives in the outside world behind?

For Marc Stein, a New York Times sports reporter, his favorite part of his bubble experience was being back in the gym, hearing the sounds of sneakers squeak, and players cheer from the benches. It’s also a chance to witness sports history in the making.

“This is my 27th season covering the NBA, and this is the most complex undertaking in league history,” Stein wrote in an email. “You had to be here to see it and cover perhaps the league’s most remarkable chapter ever, irrespective of all the complications, concerns, and access limitations.”

The return of the NBA is significant not just because of the games. It’s also a platform for the league and its players to speak about social issues, according to ESPN’s Spears.

“The loudest message they could have while they’re playing is to see Black Lives Matter on a court,” he said. “To see a white player have Black Lives Matter on the back of their shirt, to see the coaches at practice wearing different social justice messages on their shirts and players doing the same.”

Sure enough, NBA players who restarted the league’s season on Thursday night wore “Black Lives Matter” shirts and took a knee during the National Anthem.

The return of the NBA season allows players to “keep the spotlight on social justice every day.”

“I think this is an extremely great platform for the players to keep the social justice message alive at a time when it might be starting to quiet a little bit,” Spears said.

As for The Athletic’s Vardon, it may be nothing like his family vacation to Disney World last year, but he isn’t lonely or bored.

He’s mostly been working, and spending what little free time he has on video chats with friends and family and using his golf clubs to putt in his hotel room.

“Yes, it’s an enormous challenge. Yes, I’m going to be gone from my family for two months. Yes, going out into the world is dangerous right now, but this is a story that has to be covered,” Vardon said. “This is a real piece of American history happening right in front of us.”