Editor’s Note: This is the first in a three-part series on swing states in the 2020 election. Next week: The Southwest. October 20: The Rust Belt.

For longtime Republicans in the Southeast states, the region’s political evolution has started to resemble a movie running in reverse.

After Democrats dominated the region for the first century after the Civil War, Republicans mostly established their initial inroads in states such as Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia during the 1970s and 1980s in the growing suburbs of the region’s metropolitan centers. Now the recoil of voters in those same suburbs against President Donald Trump’s definition of the GOP is fueling a Democratic resurgence across states that Republicans have dominated for decades. Like a film spooling backward, Republicans are retreating along the same suburban pathways they had followed to establish their first durable beachheads in the region.

Your big questions about voting and the 2020 election, answered

Apart from Virginia, which now shades reliably blue, Republicans still hold the upper hand in the states across the Southeast. But while the GOP advantage remains lopsided in the Deep South states of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas, Democrats this year are showing clear signs of revival in North Carolina, Georgia and even South Carolina, while Florida appears headed for yet another of its trademark razor-thin results in the presidential race.

Across the region, the Democratic recovery is being propelled by two common forces: a growing minority population and a shift toward Democrats among college-educated voters of all races, particularly in the burgeoning suburbs of the region’s major metropolitan centers, from Northern Virginia and Charlotte and Raleigh in North Carolina to Charleston in South Carolina along with Atlanta and Orlando. Even Louisiana and Alabama, though still much more solidly Republican overall, haven’t been immune from these dynamics, with Democrats recently electing Gov. John Bel Edwards in the former and Sen. Doug Jones in the latter.

“Republicans are trading gains in smaller slower-growing counties for [losses in] larger faster-growing suburban counties,” says longtime Republican pollster Whit Ayres, who first moved to the Southeast in the late 1960s to attend college and then stayed for the next three decades. “That’s not a good trade-off in the long run.”

A turning tide

Through the final decades of the 20th century, and the first decade of the 21st, much of the Southeast was mostly an electoral wasteland for Democrats. From 1984 through 2016, Democratic presidential candidates carried North Carolina only once (Barack Obama in 2008), Georgia once (Bill Clinton narrowly in a three-way race in 1992) and South Carolina not at all. Democrats had carried Florida only once from 1984 through 2004 until Obama won it twice, before it reverted to Trump in 2016. Republicans carried Virginia in every presidential race from 1968 through 2004, before Democrats have now carried it in three consecutive elections.

The Republican dominance was just as pronounced in other contests. Democrats now hold both US Senate seats in Virginia, but the GOP controls all eight in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida (as well as all of them in the most ruby-red Deep South states except that of Jones, who faces long odds of reelection in Alabama next month). While Democrats have controlled the governor’s mansions most years since 2000 in Virginia and North Carolina, the party hasn’t elected a governor in Florida since 1994 or in Georgia and South Carolina since 1998.

Ayres, though an Iowa native, watched this process unfold as a student in South Carolina and then North Carolina during the 1960s and 1970s, then as a college professor and an aide and political adviser to pioneering Republican Gov. Carroll Campbell in South Carolina during the 1980s, and later as a pollster based in Atlanta starting in 1991. (He’s now in Northern Virginia.)

The GOP gains across the Southeast states over these years, Ayres noted, followed a common pattern. Across the region, “what took the Republicans up was the White middle class,” he says. “The political scientists Earl and Merle Black used to call it ‘interstate Republicanism.’ If you trace I-95 or I-26, you could find the Republican vote. It was basically a suburban middle-class base.”

Race contributed significantly to the GOP gains in Southern suburbs from the 1970s through the 1990s: Those suburbs grew in part with an influx of White parents fleeing integrated urban schools and neighborhoods. But resistance to taxes, and conservative views on social issues such as abortion and gay rights – even many White suburbanites with college degrees are evangelical Christians – also hastened the Democratic decline among those voters during those decades.

John Anzalone, now the chief pollster for Joe Biden, watched that process unfold from the other column on the ballot. Born in Michigan, he relocated to Alabama in 1990. He arrived just in time for the GOP landslide during the 1994 midterms, as a backlash against Clinton’s chaotic first two years swept away a generation of Southern House Democrats who had doggedly held on to seats, often in mostly White rural areas, that had started voting Republican for president as far back as Richard Nixon. Over the next few years, Republicans gained majorities in Southeastern state legislatures that Democrats had typically controlled since Reconstruction after the Civil War.

“The Republicans in the 1980s and early 1990s won the branding war on what the Democratic Party stood for,” Anzalone says. “It went from people saying in focus groups that ‘[Democrats] are for the little guy’ to they are for taxes, big government, welfare – which is the code word for Blacks – and abortion.”

Virginia

Through the 1990s, Democrats managed only a few cracks in the towering red advantage across the region. The party’s first hint of recovery came in Virginia soon after 2000, with the elections of Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, in each case first to the governorship and then to the Senate. In 2004, Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry, though still losing the state, made gains in the prospering Northern Virginia suburbs, becoming the first Democrat since Lyndon Johnson in 1964 to carry booming Fairfax County, outside Washington.

Since then the balance in Virginia has clearly tipped blue, with Democrats controlling not only both US Senate seats but also the governorship and state Legislature. Virginia was considered enough of a swing state in 2016 that Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton sought to lock it down by picking Kaine as her running mate; this year, both sides consider it essentially impregnable for Democrats.

Virginia vividly encapsulates the two underlying trends reconfiguring the region’s politics. One is increasing racial and ethnic diversity, as growing numbers of Hispanics and Asian Americans have joined the state’s substantial African American community. In 2004, voters of color cast about 2-in-10 of the state’s ballots, according to census figures. By 2016, that number had increased to 3-in-10, according to analysis by the States of Change project, a research collaborative of three liberal-leaning groups – the Center for American Progress, the Brookings Institution and the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group – and the centrist Bipartisan Policy Center. The project studies the changing composition of the American electorate and its implications for policy and politics.

In 2020 the minority share of the Virginia vote will edge up further to 32%, according to States of Change projections shared exclusively with CNN. Exit polls show that Democrats consistently amass huge advantages with Virginia’s Latino, Asian American and Black voters alike.

Over that same period, Whites without college degrees, the bedrock of the GOP coalition, have fallen from nearly half of Virginia’s voters to one-third in States of Change’s 2020 projection. College-educated Whites, who have migrated toward the Democrats in the state over that period, have stayed roughly constant at just over one-third of the state’s voters.

The shift of those well-educated Whites underscores the second big change that has rearranged Virginia’s politics: the widening Democratic advantage in the largest population centers, including the suburbs of Washington and Richmond. In 2016, Clinton won five of the seven Virginia jurisdictions (including the city of Virginia Beach) that cast the most votes that year – and carried the entire group by a crushing combined margin of 364,437 votes. As recently as 2004, President George W. Bush had carried five of those seven places by a combined margin of about 32,000 votes. Just in Fairfax County, the Democratic advantage ballooned from about 34,000 votes for Kerry to nearly 200,000 for Clinton. In the 2017 governor’s race, Democrat Ralph Northam won more than two-thirds of the vote in Fairfax, by far the state’s largest county.

Over this period, Republicans have consistently dominated the state’s small town and rural areas, and Trump widened their margins in those areas further in 2016. But that hasn’t come close to offsetting their losses in the population centers.

At varying speeds, the other region’s key battlegrounds are on the same moving walkway that has transformed Virginia. In all of them, Democrats are benefiting from growing diversity and improved performance in burgeoning white-collar suburbs, while Republicans try to hold back the tide by maximizing their advantage among White and mostly Christian voters in stagnant or shrinking exurban, small-town and rural places.

North Carolina

“Obviously in North Carolina, the Virginia process has gone quite a ways and Georgia is next on the list,” says Jim Guth, a Republican activist and longtime political scientist at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. “South Carolina brings up the rear in these kinds of transitions, although we see signs of it here as well.”

As in Virginia, a major component of the North Carolina story is the growth in the minority population, as the long-established Black community is joined by a steady influx of Hispanics and Asian Americans. States of Change expects Black voters to cast a little over 1-in-5 of the state’s votes in 2020 and the contribution of those other groups to push the total for people of color to fully 3-in-10. That’s up from about 1-in-4 in 2004.

Maybe even more important to Democratic hopes have been their improving positions among college-educated White voters and in the large metropolitan areas more broadly. The metros centered on Charlotte and the Raleigh-Durham-Research Triangle Park area have been booming as sharp young college graduates migrate to the state to fill jobs in health care, pharmaceuticals, high-technology and finance.

“In Durham, where I’m located, the number of high-end apartments, condominiums, apartments, in the city of Durham, not in the suburbs, is staggering,” says Kerry Haynie, an associate professor of political science and African American studies at Duke University. “There are million-dollar penthouses in the city of Durham and that’s unheard-of.”

In 2004, Kerry marked a milestone when he carried Mecklenburg County, centered on Charlotte and its suburbs, by nearly 12,000 votes, the biggest margin of victory there for any Democratic nominee since Franklin Roosevelt in 1944; by 2016, Clinton carried Mecklenburg by more than 139,000 votes. Wake County, centered on Raleigh, in 2004 gave Bush a margin of greater than 7,000 votes; Clinton carried Wake by nearly 107,000 votes. Overall, Clinton carried the five North Carolina counties that cast the most votes in 2016 by a margin of more than 408,000, compared with Kerry’s advantage of only about 34,000 votes in those same places.

Yet such was Trump’s strength in rural communities that he won North Carolina nonetheless – and by an even larger margin than Mitt Romney had in 2012. Trump won 76 of the state’s 100 counties and improved on Romney’s vote share in an even larger number of them, 79, according to an analysis of the results provided by Polidata, a political data firm.

Multiple recent North Carolina polls show that Biden is positioned to split or narrowly win college-educated White voters in the state, which would represent an improvement over both Clinton in 2016 and Obama in 2012 and 2008, according to exit polls. Biden is also consistently posting big advantages among African American voters (though he won’t match Obama’s overwhelming advantage and may struggle to entirely equal even Clinton’s number.)

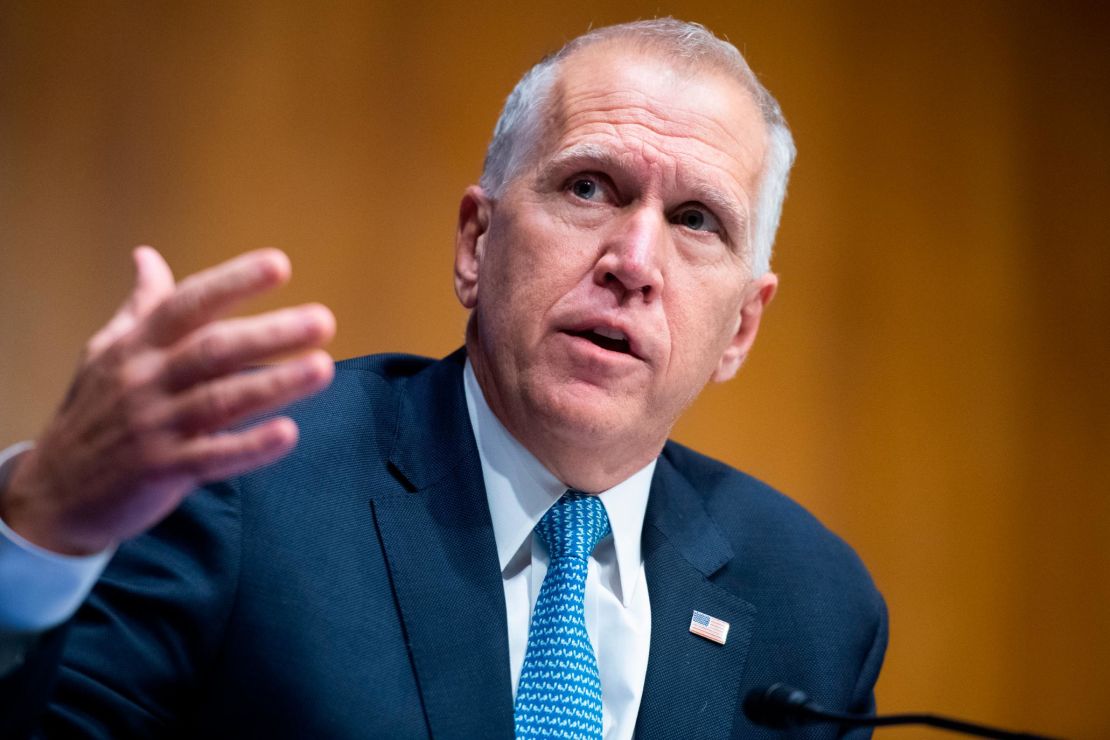

Trump is still overwhelmingly strong among White voters without college degrees there: Recent surveys by pollsters from CBS to Fox News and Monmouth University all show the President still winning about two-thirds or more of them. But even that may represent a slight decline from his support in 2016 back to something closer to the deficits Obama faced when he won the state in 2008 and only narrowly lost it in 2012, according to exit polls and States of Change calculations. Those same polls show similar dynamics, though a deeper blue tilt overall, in the Senate race, where Democratic challenger Cal Cunningham has consistently led Republican Sen. Thom Tillis.

Even Democrats agree that Trump’s continued strength among blue-collar and rural Whites makes North Carolina one of the toughest swing states for Biden.

Georgia

Yet as the Trump campaign struggles to hold North Carolina it has found itself facing unexpectedly strong pressure in Georgia, where a succession of surveys has shown the former vice president essentially tied or even slightly ahead.

Georgia has grown even more diverse than Virginia or North Carolina. With expanding Asian and Hispanic populations and a steady influx of African Americans reversing the “great migration” North to return to the Atlanta area, Georgia has seen the minority share of its vote rise from about 3-in-10 in 2004, according to the census, to nearly 4-in-10 in the States of Change projection for 2020.

And like Virginia and North Carolina, Georgia has seen economic activity and population growth increasingly concentrate in a few urban centers, particularly the Atlanta metropolitan area. But it has taken Georgia Democrats longer to establish a foothold in the suburbs of that booming community. In 2004, Kerry won only about one-third of the vote in both Cobb and Gwinnett, the giant suburban counties outside of Atlanta; even as recently as the 2014 governor’s race, Democrat Jason Carter won only a little over 40% of the vote in both, though he was Jimmy Carter’s grandson.

But the voters in these well-educated and diverse communities have recoiled from Trump’s definition of the GOP. Clinton won both of them by narrow margins in 2016 and Stacey Abrams won them by bigger margins in the 2018 governor’s race, when Democrats also won a US House seat there and flipped several Republican state House districts.

Georgia’s overall dynamic in 2016 closely resembled North Carolina’s but tilted further toward the GOP: Clinton won the five Georgia counties that cast the most ballots by more than 421,000 votes, compared with an advantage of fewer than 45,000 votes for Kerry. But overall Trump won 128 of the state’s 159 counties and improved on Romney’s margin in 122 of them, according to Polidata’s analysis. Similar dominance in exurban, small-town and rural areas allowed Republican Gov. Brian Kemp to beat Abrams despite her metro gains in 2018.

Republicans are counting on the same equation to hold the state for Trump next month. But the party’s erosion in the fast-growing suburbs may be intensifying: While exit polls showed that Abrams won 40% of college-educated Whites (already roughly double the level Carter attracted in 2014) several recent polls show Biden pushing past that number into the mid-40s now. And as in North Carolina, he’s slightly reducing the Democrats’ recent deficit with blue-collar Whites (though Trump is still drawing nearly three-fourths of them). Asked if Trump retained enough blue-collar strength to overcome his continued slide in Georgia’s white-collar suburbs, Ayres says, “We’re going to find out. … It’s pretty close.”

South Carolina

Wedged between North Carolina and Georgia, South Carolina has seemed immune to their trends. Though its minority population has grown, it has not seen the big influx of college-educated information-age workers that has changed the political equation for its neighbors. Although Clinton won big in the county centered on Columbia, the state capital, and narrowly carried Charleston, overall Trump carried the five counties that cast the most ballots there by nearly 79,000 votes. Combined with his strong position among evangelical, blue-collar and non-urban Whites, Trump, remains favored in the state.

But Democratic US Senate candidate Jaime Harrison has shocked Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham by replicating the formula that has revived Democrats in the neighboring states. Polls show Harrison, who’s African American, drawing more than 90% of Black voters and pushing toward 50% among college-educated Whites. Graham is caught in the same demographic squeeze as Republicans elsewhere across the region: He’s still drawing more than two-thirds of Whites without college degrees, but they may cast only about 40% of the votes this fall, according to the States of Change projections, down from about half in 2004.

Guth, the political scientist and Republican activist, expects both Trump and Graham to win but believes that, win or lose, Harrison’s strong showing points toward a more competitive future in the state. “Quite clearly the Republican strategy on doubling down on White working-class non-college-educated voters is reaching its limits,” Guth says. “Certainly you see the Republican majorities eroding in the urban areas, especially in bad years.”

Florida

Florida, the region’s largest prize, with 29 Electoral College votes, both embodies and puts its own characteristic spin on these dynamics. Though Republicans dominate most local offices, Florida has become the most narrowly balanced mega-state in presidential politics. Steve Schale, a veteran Democratic Florida strategist, recently calculated that of some 51 million votes cast in presidential elections there since 1992, fewer than 20,000 separate the two parties. Seven statewide races in the past decade, Schale notes, have been decided by 1.2 percentage points or less.

For campaigns, Florida is a Rubik’s Cube of almost impossible complexity, with 10 large media markets; a White population divided not only between college- and non-, younger and older, but further split between conservative Midwestern retirees on its west coast and more liberal Northeastern retirees in its southeast; and a non-White experience shaped by the striated differences between Central and South Americans, Cuban Americans and Puerto Ricans, and Caribbean and native-born Black voters. Except for Obama’s two victories, Democrats in particular have found the puzzle almost impossible to solve: Whenever they gain on one of these fronts, they seem to suffer offsetting losses on the other that leave them just short.

“The first law of Florida elections,” says Democratic pollster Carlos Odio, “is that for every trend there is an equal and opposite trend somewhere else.”

At the highest level, Florida’s political evolution has followed the tracks rolling through the rest of the region: growing Republican strength with blue-collar and rural Whites has offset the Democratic gains in big urban centers and an increasing non-White population. Those counterpoised trends, says Schale, have “led to this kind of stasis in Florida, where it stays the same.”

Democrats are facing another permutation of Florida’s Rubik’s Cube this year. Biden is running better than any recent Democratic nominee not only among college-educated but also older Whites. That should be enough to give him the advantage in Florida – and in fact he’s consistently led narrowly in most polls there. But Biden is underperforming among Hispanics, not only Cuban Americans returning to the Republican roots that Clinton somewhat loosened, but also those from Central and South America and, in some Democratic surveys, even Puerto Ricans. With the state, as always, teetering between such crosscutting factors, few on either side would be surprised if Florida produces another photo finish.

In the long run

Narrow outcomes in Florida, by this point, don’t shock anyone. More surprising is the extent of Democratic strength in the presidential and Senate races in North Carolina and Georgia and even the Senate contest in South Carolina. Most unnerving for Republicans is that in each of those states, Democrats are riding the same two waves – growing diversity and increasing strength in well-educated suburbs – that carried Virginia from reliably Republican in the 1990s to a swing state in the first years of this century to safely blue now.

Ayres and Guth are skeptical that at any point in the near future North Carolina and Georgia, much less South Carolina, will tilt as reliably Democratic as Virginia. But neither sees Republicans restoring their recent dominance.

“North Carolina and Georgia are much more Southern,” says Ayres. “I think purple is much more likely, because they are just much more Southern states and you don’t see the Research Triangle [in North Carolina] or Cobb and Gwinnett [in Georgia] becoming like Fairfax” in providing Democrats such lopsided margins.

Haynie, who directs Duke’s Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity and Gender, agrees that these Southeastern states are unlikely to become Virginia anytime soon. But he predicts that all of them will become more challenging for the GOP as long as it aims its agenda primarily at the priorities and resentments of shrinking populations of non-college and evangelical Whites while alienating the groups in those states that are growing: white-collar professionals and people of color. “Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina look similar in terms of the trajectory of the demographic shifts,” he says.

The Electoral College, explained

Democrats may be unlikely to reach a position of dominance in the Southeast states, but even a more competitive standing, in which the party can occasionally win Senate seats and Electoral College votes from the region, would significantly change the national political equation. Pollster Anzalone, who persevered through the Democrats’ darkest years across the region, believes Trump represents an inadvertent bookend to the process that propelled the GOP to its Southeastern dominance. Just as Republicans successfully defined Democrats as out of the mainstream to most White voters during the 1980s and 1990s, he says, Trump is stamping his own party today to many well-educated voters as biased against Blacks and immigrants, hostile to science and ideologically extreme.

“The Republicans won the branding war on the Democrats,” Anzalone says. “The reason it’s reversing is interesting, because they are losing the branding war by themselves. They are their own problem in the branding war. Early on, they did a really good job of branding the Democrats, and now they are creating their own branding problems by not keeping up with voters’ attitudes.”