Editor’s Note: Jack Turban MD (@jack_turban) is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Stanford University School of Medicine. The views expressed here are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

As physicians, my colleagues and I have the honor and privilege to help people through some of the most difficult times of their lives. Along with this privilege come some challenging situations. Once at three in the morning, I was paged to see a patient going through alcohol withdrawal. The moment I walked into his room, he grabbed my pager from my scrubs and threw it against the wall. He screamed homophobic slurs in my face. I was tired. My shoulders tightened with anxiety, and I steeled myself against memories of middle school bullies summoned by this patient’s screaming.

I pushed through and made sure he got the medical interventions he needed. Had he not received this timely medical care, his substance use would have threatened his life. My medical training taught me to prioritize his health over my pain at his words or beliefs that homophobia like his is morally wrong. It is my job to do that. Similarly, I would expect a doctor who thinks alcohol use disorder is a “moral failing” to still offer this patient evidence-based medical care.

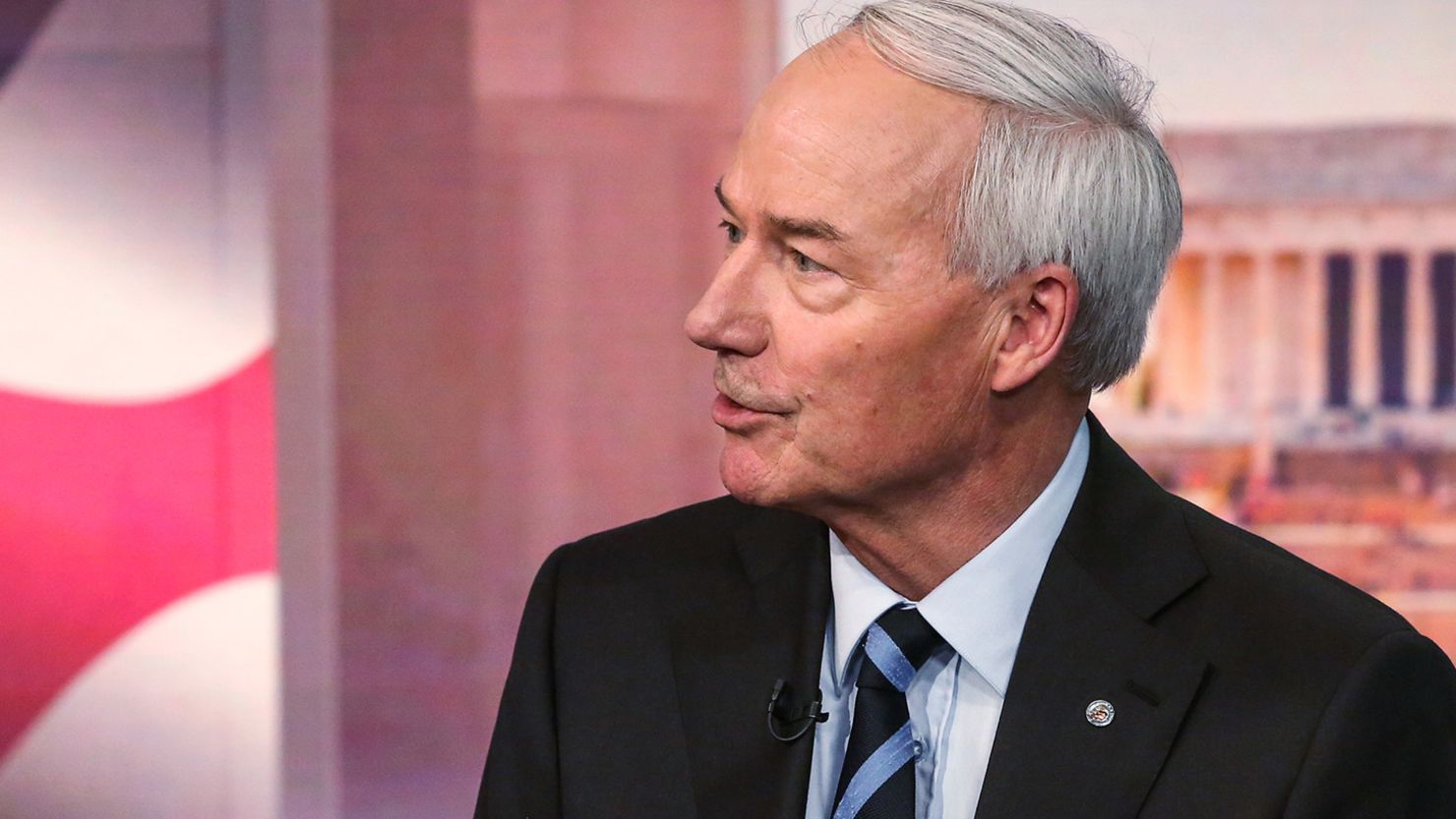

Sadly, not all politicians think the same way. This week, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson signed the so-called Medical Ethics and Diversity Act into law. The law allows a wide range of health care workers – doctors, pharmacists and even insurance companies – to refuse to provide non-emergency healthcare based on personal “moral” objections. This new law is dangerous and directly contradicts the professional responsibilities we have as health care providers.

As a gay man in medicine, I’ll be the first to tell you that we should have diversity in the profession. It’s important to have physicians from all races, ethnicities, religious backgrounds, gender identities and sexual orientations. I applaud that idea of a bill that promotes diversity in medicine. But Arkansas’s new “Medical Ethics and Diversity” law does no such thing. It is unethical and targets diverse patients, trying to take away their health care.

The most obvious damage this law will cause for the people of Arkansas will be to limit access to certain treatments that have become politicized. This will likely include things like gender-affirming surgeries or medications for transgender people and abortion care. Of note, the state legislature also just passed a law that would explicitly outlaw gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth, despite opposition from major medical organizations and data linking gender-affirming care to lower odds of transgender people considering suicide. That bill is awaiting the governor’s signature.

But Dr. Jennifer Gunter, obstetrician gynecologist, women’s health expert and author of “The Menopause Manifesto,” noted in an interview with me that the negative impacts of the Medical Ethics and Diversity Act may go beyond these highly politicized treatments. “What if your insurer decides your cancer is a result of immoral behavior because you were once a smoker? The potential for abuse is huge and frightening.”

This new law means that health care can be blocked at various stages along the health care delivery chain. Let’s say a doctor agrees to prescribe your medication – a pharmacist could still refuse to dispense it based on whatever “moral” grounds they assert. Even if the physician and pharmacist agree to give you the medication, your insurance company could refuse to pay for it.

Proponents of the law have been quick to point out that it only applies to “non-emergency care.” But we need to keep in mind that people die from “non-emergencies.” Let’s say a lesbian woman lives in a small town where there are only a few doctors. She develops diabetes, and the doctors in the area refuse to examine her and give her insulin because they think living as an out lesbian woman goes against their personal “morals.” This woman’s diabetes will progress. She will eventually lose feeling in her hands and feet. She may become blind. Her diabetes will progress and eventually she will end up in the emergency room, where the doctors will need to treat the emergency. But at that point, it will likely be too late, and she will die an early death.

This bill has left many people in Arkansas horrified. I spoke with one of them recently: Chris Attig, an 11-year US Army Veteran who lives in Little Rock, and is the father of a transgender child. He pointed out that Arkansas is a small state, and that almost all of the major hospitals are “faith-based.” He worries that if these hospitals refuse to treat trans people, then his son will simply go without medical care.

Like Chris, many have seen the new law as being primarily directed toward transgender people. Arkansas has had a flurry of anti-trans legislation this year: a new law that bans transgender girls from playing on girls sports teams, a bill that outlaws gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth and now this “medical conscience” bill.

When I asked why there has been so much legislation about transgender people in Arkansas this year, State Rep. Deborah Ferguson told me she believes conservative groups in the area are simply out of issues, “Honestly I think the Family Council has run out of things to fight about. They need to look for something to validate their existence.” State Sen. Kim Hammer, lead sponsor of The Medical Ethics and Diversity Act in the Senate, did not – as of the time of this writing – respond to my question on what prompted his introduction of the bill.

It seems clear that the new law will lead to direct negative impacts on health, and potentially deaths. But there will also be more insidious indirect effects. Research has consistently shown that bills like this cause cultural shifts. If the local news and politicians tell LGBTQ people that they can be discriminated against in health care, people are likely going to think it’s okay to harass them in other settings. Sadly, LGBTQ people often take those messages to heart. As a psychiatrist, I sit with many LGBTQ people who have been told all their lives that being LGBTQ is wrong or amoral. At a certain point, they start to internalize those messages, resulting in low self-esteem, anxiety and depression. This is a primary reason for high rates of suicide among LGBTQ people.

One of the best ways of illuminating the risks posed by this Arkansas law is a major study of how marriage equality impacted adolescent mental health. In states that passed marriage equality before it was legal nationwide, adolescent suicide attempts dropped. It obviously wasn’t because teenagers were getting married; it was because these conversations about the rights of LGBTQ people impact mental health dramatically. Similarly, laws permitting refusal of services to LGBTQ people have been shown to have substantial negative impacts on mental health.

The new law will also likely negatively impact Arkansas’s economy. Similar lawsuits have been challenged in the courts, resulting in substantial legal fees the state would need to pay. The Idaho attorney general’s office, for instance, estimated that it would cost Idaho approximately $1 million if it needed to fund a protracted legal battle over an anti-trans birth certificate bill. Some states have also seen major companies pull resources out of their state in response to similar legislation. These are resources that would be better spent fighting Covid-19 and other health challenges impacting the state.

Doctors and medical professionals train long and hard to have the privilege to care for people during some of the most challenging times in their lives. This comes with responsibilities. As a profession, we have dedicated ourselves to putting health above all other beliefs we may hold. The new Arkansas law goes against these medical ethics. I can only hope that, despite this amoral legislation, the doctors of Arkansas will uphold their duty to treat all people.