There comes a point in every awful horror movie where a character does something so careless and shortsighted a viewer loses faith in the storyteller.

There’s the hapless victim who can’t flee from the monster without falling, the stubborn homeowner who won’t move out of a haunted house, and my favorite: the person who walks toward, not away, from a sinister noise at night while asking, “Hello, is anyone there?”

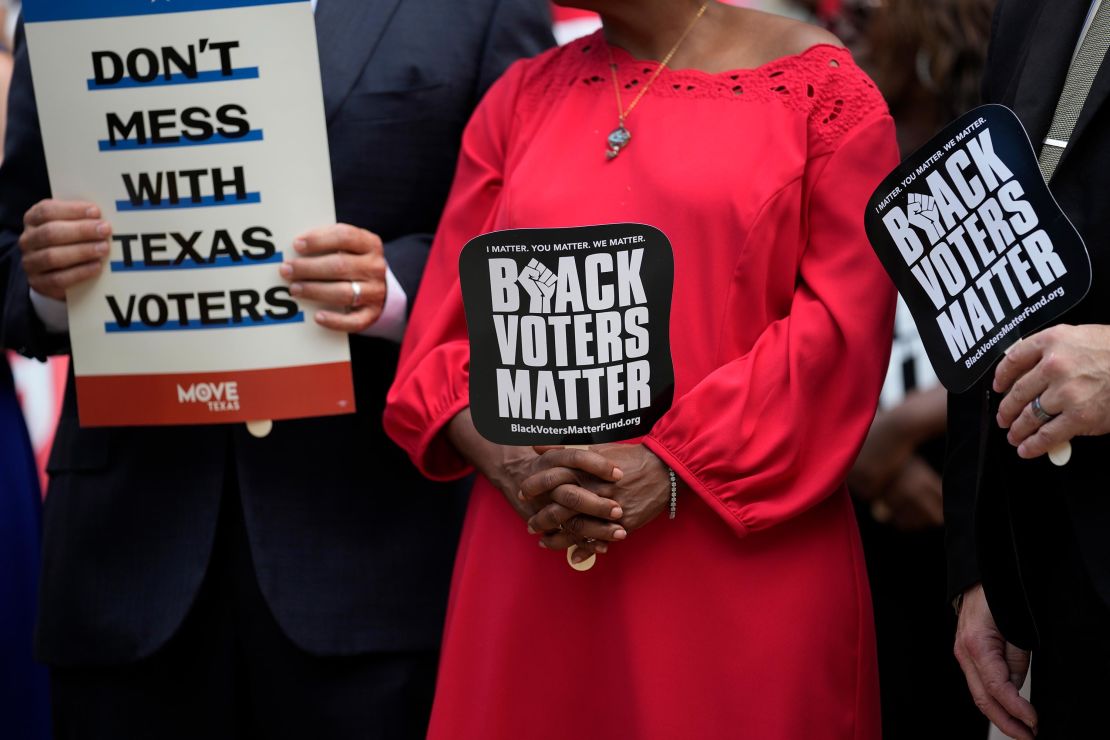

As I watch some Democrats handle the voting rights issue, I’m seeing a replay of a 19th-century political horror story. It ended with Black voters losing faith in the leaders who were supposed to protect them.

President Biden has called voting rights “the single most important” issue and described a wave of voter restriction bills recently passed by Republican legislatures across the US as “Jim Crow on steroids.”

Yet he has refused to throw the full weight of the Oval Office behind passing two pending voting rights bills in Congress. He has stopped short of embracing calls to jettison the filibuster – the parliamentary tactic Republicans can use to halt a voting rights bill – because he says it would “throw the entire Congress into chaos.”

Read more from John Blake:

He’s focused instead on passing a bipartisan infrastructure bill that could rejuvenate the economy and appeal to a broad swath of voters.

But for anyone who knows this country’s shameful voting rights history, Biden is following a script that once doomed Black voters and made the rise of Jim Crow possible.

Biden and Democratic leaders who prioritize infrastructure in part to broaden their appeal to reluctant White supporters are making the same mistake White political allies of Black voters made in the late 19th century. That’s when the more progressive American political party of that era – the Republican Party – abandoned Black voters to focus on an economic agenda that emphasized infrastructure and uniting a country that was bitterly divided by race.

That blunder gave us a century of Jim Crow segregation, reduced the Republican Party to a “dying institution” ‘in the South and forced countless Black Americans to confront an uncomfortable truth that many are now facing again:

Our White political allies are rarely willing to match the intensity and cunning of our political opponents.

When chickens ask foxes for help

Evoking Jim Crow may cause some people to cringe because the comparison seems overblown. No White vigilantes are gunning down or lynching would-be Black voters. No White mobs are brazenly murdering Black elected officials or launching what’s been described as the nation’s only successful coup – against a Southern city filled with Black leaders. All of this happened during that era.

But there are two lessons today’s Democratic leaders can learn from the mistakes their White counterparts made in the late 19th century:

Economic appeals to White voters driven by racial resentment have limited value. And when you refuse to go all out to protect your most loyal voters, the results can be disastrous.

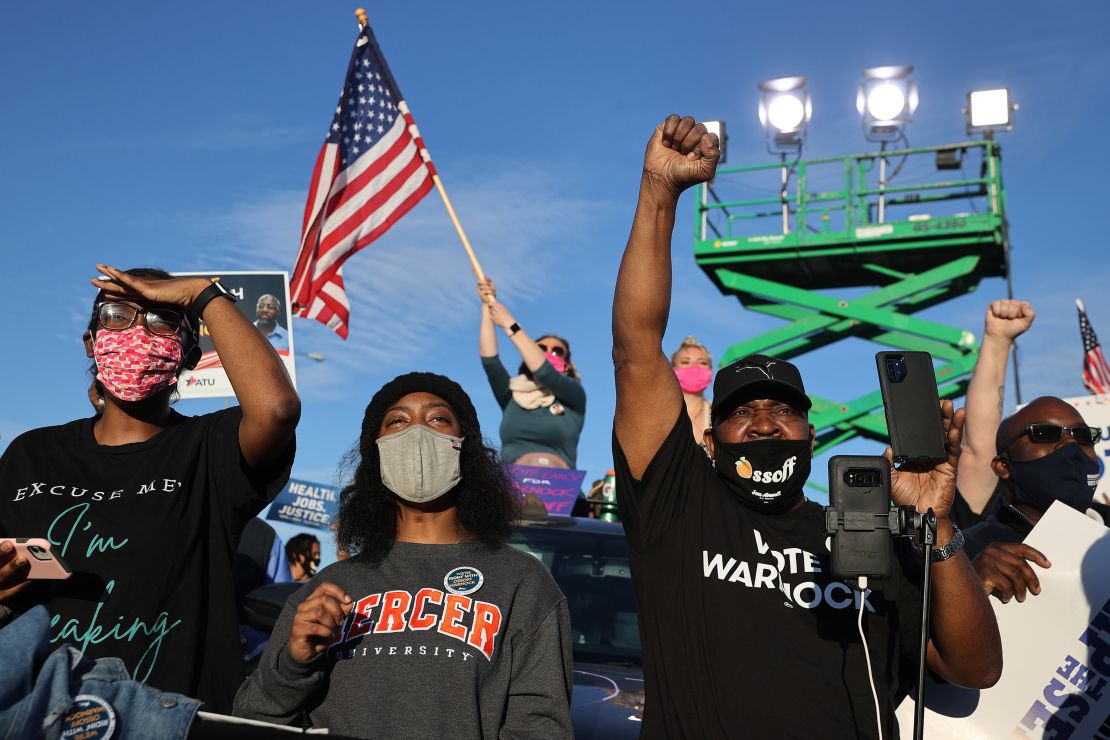

These aren’t abstract lessons for me. I am a Black voter in Georgia, the epicenter of the new voting rights struggle.

I watched Black voters save Biden’s presidency during his primary run last year. I glowed with pride when he picked Kamala Harris, my classmate at Howard University, to be his vice president. I watched Black voters flood voting precincts in a pandemic and honk their horns in jubilation after they delivered the Oval Office and control of Congress to the Democrats.

What I am seeing now, though, is a rising sense of betrayal among Black voters. Many don’t think Democratic leaders are pushing hard enough on voting rights. More are frustrated by Democratic leaders like Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who says he won’t support gutting the filibuster and insists on Republican buy-in to support a new voting rights bill. (He did propose a compromise on voting rights legislation that won the support of voting rights activist Stacey Abrams.)

Leonard Pitts Jr., a Pulitzer Prize winning columnist, captured some of this bitterness when he called Manchin’s reasoning “nonsensical.” Pitts also alluded to the “For the People Act,” a bill to expand voting rights, when he posed a rhetorical question to Manchin:

“Would you decline to support a For the Chickens Act solely because the foxes refused to sign on?”

Why some White voters won’t care if you build them a bridge

A Black voter who voted Republican in the late 19th-century South could have related to some of Pitts’ sarcasm.

Black voters in the South were then the most loyal supporters of the Republican Party. The Republicans were the party of Abraham Lincoln, the “Great Emancipator,” and the driving force behind Reconstruction, which lasted roughly from 1865 to 1877. It was the nation’s first genuine attempt to build a multiracial democracy.

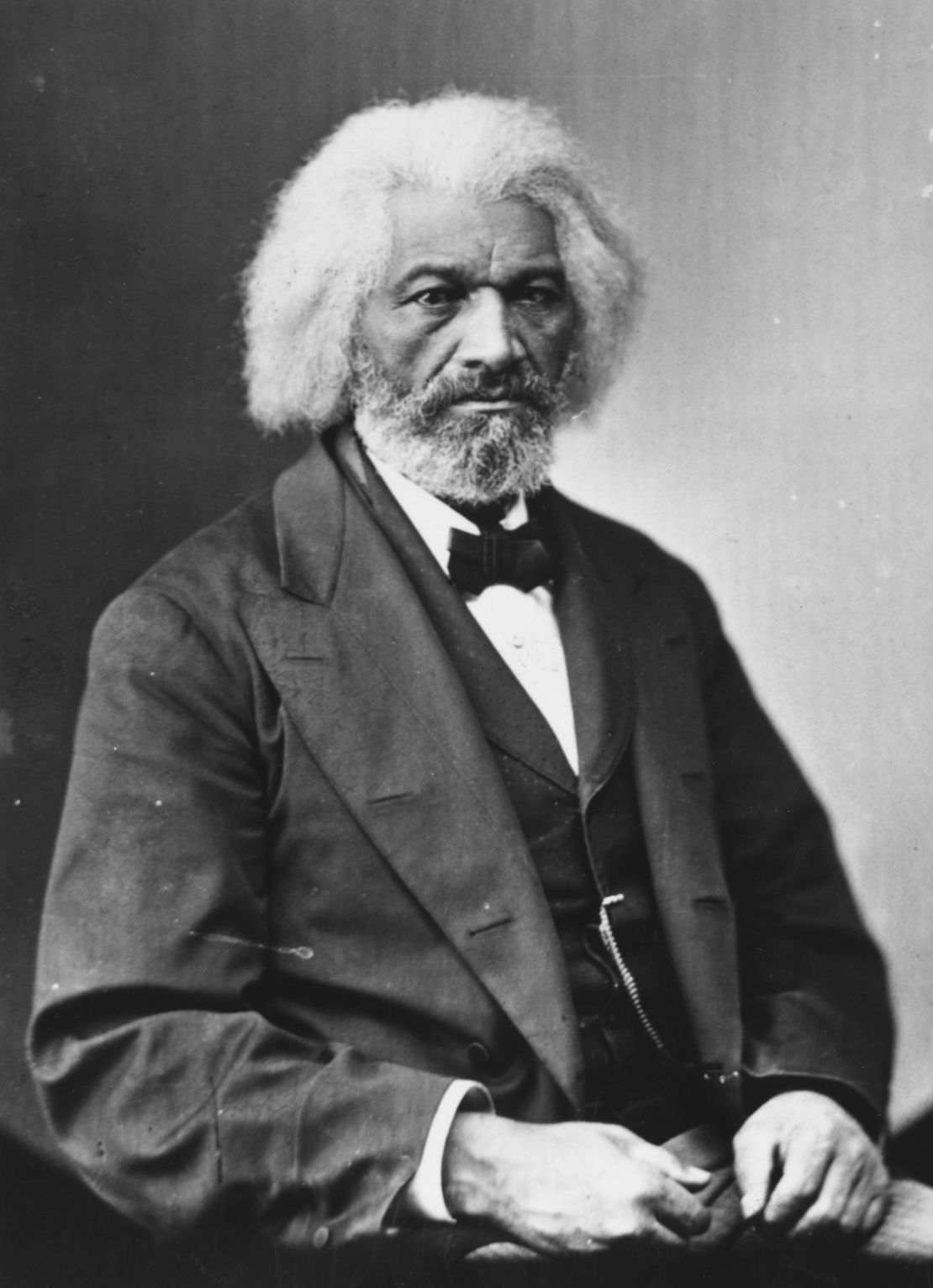

Those Republicans were strong supporters of Black voting rights. Black Americans were so loyal to the party that Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist and civil rights icon, once said, “The Republican Party is the ship and all else is the sea around us.”

But as White resistance to Reconstruction grew, the Republican Party gradually began to treat Black voters as castaways. GOP leaders said that the party shouldn’t become too dependent on Black voters and should craft an economic message that would appeal to more White voters, says Richard White, author of “The Republic for Which it Stands,” an acclaimed book that explores US history from Reconstruction to the end of the 19th century.

A central part of Republicans’ economic message to reluctant White voters was infrastructure: They vowed to rebuild the roads, railways and ports throughout the South.

“They said we’re going to give you economic opportunity,” says White, a professor of American history at Stanford University. “We’re going to build an economic infrastructure you can use. You are going to be able to increase your standard of living. And that’s why you’re going to join the Republican Party.”

That approach didn’t work in the South. Racism trumped economics. Many White Southerners from the Civil War generation saw the Republican Party as “an alien embodiment of wartime defeat and black equality,” the historian Eric Foner said in his classic book on that era, “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution.”

White resistance to Black voting rights ground down the will of many Republican leaders. Black political power was crushed by a combination of White terrorism, a wave of voter suppression laws and an indifferent Supreme Court that turned a blind eye to injustice.

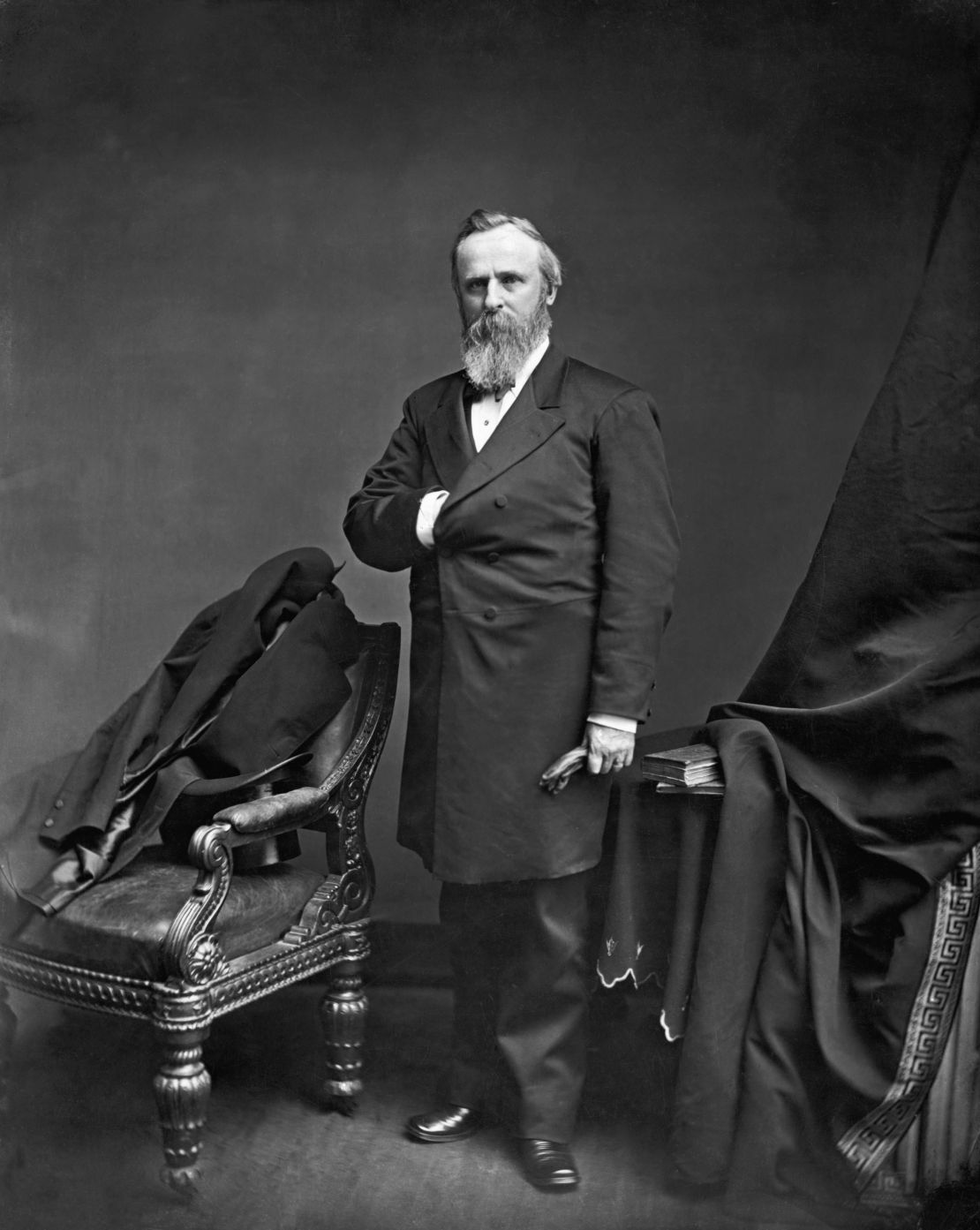

Reconstruction roughly ended with the disputed presidential contest of 1876. An election too close to call was resolved after candidate Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to a backroom deal that resulted in him pulling troops out of the South in exchange for the presidency. The Republican Party ceased being a major player in the South. Democrats became so dominant that the region became known as the “Solid South.”

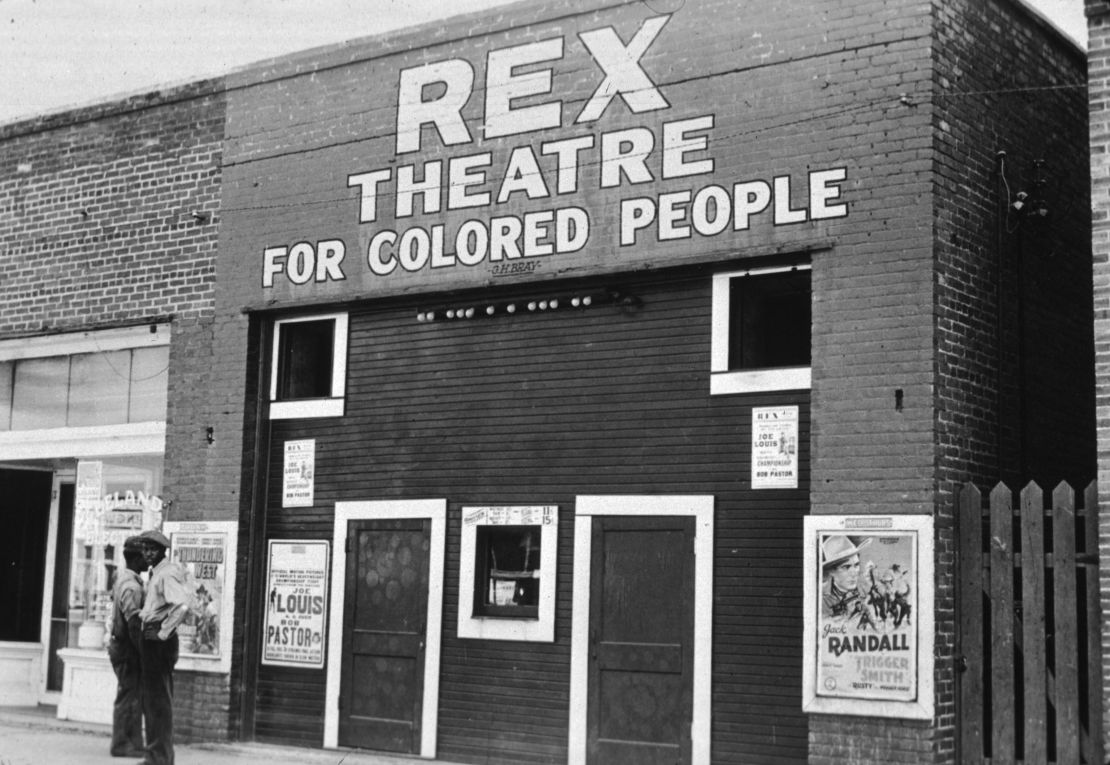

What followed was a century of Jim Crow segregation throughout the South that only ended with the rise of the civil rights movement in the mid-1960s. That’s when the Democratic Party began attracting massive numbers of Black voters because of its support for civil rights.

The reasons why Reconstruction ended are complicated. But one lesson contemporary Democratic leaders should take from that era is simple: An economic appeal to White voters consumed by racial grievances can only go so far.

Many Southern White voters were willing to sacrifice the economic benefits of Reconstruction – the regions’ first public schools, rebuilt roads and railroads, the construction of public hospitals – to prevent what some called “Negro Rule.”

White, the historian, says Democratic leaders touting the crossover appeal of the infrastructure bill “sound like moderate Republicans during Reconstruction.”

“That’s why I think the infrastructure argument is ridiculous, because in the South they were more than willing to hurt themselves if in fact they could hurt Black people more,” White says.

That impulse among some White voters survives today.

Look at the resistance to Obamacare. The Democratic Party’s passage of a national health care law that helps many struggling White families did not turn many conservative White voters into Democrats. Many red states still won’t accept the Medicaid expansion under Obamacare despite the financial and health benefits.

Or consider the impact of Biden dispatching stimulus checks to White voters.

A Washington Post reporter recently traveled to an impoverished, rural Ohio county whose White voters overwhelmingly voted for former President Trump. Though virtually all of them said they benefited from Biden’s stimulus checks, virtually none said the help would lead them to support Democrats.

The lesson: Building a new road won’t build a new bridge to reluctant White voters who despise Blacks.

Both parties have taken Black voters for granted

The White political allies of Black voters made another big mistake that Democrats may be making now.

They’re forgetting to “Dance With the One That Brought You.”

That’s the title of a song by country music star Shania Twain. The title also reflects a popular sports expression which advises coaches to stick with the players that helped them win.

The Republican Party in the 19th century ignored that rationale. Black voters in the South were crucial to Republicans’ success in the early days of Reconstruction. They were the party’s most loyal supporters. At one point in the late 19th century, there were an estimated 2,000 Black Republicans holding office throughout the South.

As White resistance to Reconstruction mounted, though, Republican Party leaders shifted their emphasis from racial equality to big business.

“Republicans started taking the Black vote for granted, and the Republican Party were always divided,” the historian, Foner, said in a USA Today interview. “There were those who said, ‘We got to really defend the Black vote in the South.’ And others said, ‘No, we’ve got to appeal to the business-minded voter in the South as the party of business, the party of growth.”

Many Black supporters of the Republican Party felt betrayed. They were the backbone of the GOP in the South but watched Republican leaders do nothing as Black Southerners were being slaughtered while trying to vote.

Henry Adams, an ex-slave who fought for the Union in the Civil War, once told congressional investigators in 1880: “The whole South — every State in the South — had got into the hands of the very men that held us slaves.”

When a political party allows its political opponents to restrict access to the vote, the impact can last for multiple generations. That happened in the Jim Crow South. The US didn’t become a genuine democracy until the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Voting rights advocates warn that some version of a Jim Crow 2.0 could repeat itself today – minus the raw violence but with an array of new tactics that restrict voting by Black Americans.

Nse Ufot, a voting rights advocate in Georgia, said that if Democratic leaders can’t replicate the staggering turnout from last November’s presidential election, then “We’re f—ed.”

She used another f-word when she talked about Biden’s recent speech on voting rights.

“When I think about the f-word that cannot be said on television, I didn’t think it was the filibuster,” she told me.

Ufot says she and other Black voters have often felt that the Democratic Party takes their vote for granted. Many now also face the dilemma Black voters faced in the late 19th century South – the alternative is worse. They can’t envision voting for today’s Republican Party, which they view as dominated by White supremacists.

Still, some Black voters could make a third choice that should frighten Democrats: to not vote at all.

Ufot says if the voting rights bill fails, many Black voters in swing states like Georgia may wonder if standing in long lines and taking time off for work to navigate a thicket of voting restrictions is worth it.

“We run the risk of people withdrawing from the process because the cost of participation is too high and they don’t feel like any party represents their interests and will fight for their agenda and priorities,” she says.

The potential death spiral facing the Democratic Party

Black voters won’t be the only ones hurt if Democratic leaders don’t go all out to protect voting rights. The party itself could suffer from a modern version of the death spiral that doomed Republicans in the Jim Crow South.

If the Democratic Party doesn’t pass new voting protections, it could lose the House, Senate and White House within the next four years, says Ronald Brownstein, a senior political analyst at CNN, in a recent Atlantic magazine essay.

He says the country is facing a ‘turning point” in the voting rights battle that will determine whether its democracy “grows more inclusive or exclusionary.” He writes that Republican voter restrictions “amount to stacking sandbags against a rising tide of demographic change” and that millennials and Gen Zers represent the most racially diverse generation in American history.

If Republicans eventually impose red state voting rules on blue states, Democrats may not be able to pass national voting rights rules “for another 50 years,” said one Democratic senator quoted in Brownstein’s essay.

For Democrats, passing a new voting rights bill is a question of survival, Elie Mystal, a writer with The Nation magazine, said during a recent interview with Slate.

“There are entirely too many Democratic senators and establishment folks who do not see the existential threat to their own jobs if these voter suppression laws are allowed to stand,” she said. “They think they can still convince that middle-of-the-road White person that left the party during the Reagan years… They don’t understand that the base of their party is these Black and brown people who turn out for them. They don’t understand that they cannot win if they do not have overwhelming turnout from Black and brown communities.”

Other voting rights advocates are less pessimistic. They say that voter suppression laws aimed at Black voters can sometimes backfire.

“Black people have a history – when you make us mad, we turn out,” says Timothy McDonald, an Atlanta pastor who founded the African American Ministers Leadership Council, the group which created the “Souls to the Polls” get-out-the-vote movement among Black churches nationwide.

McDonald says it’s time to do away with the filibuster if it’s used to stop a new voting rights bill. But he also supports the Biden administration’s focus on passing what could possibly be two major infrastructure bills. New construction offers tangible signs of progress that could even cause some White, conservative voters to switch their votes to Democrats, he says.

“Even Bubba might say, ‘I don’t like Democrats,’ but that’s a good thing there,” says, McDonald, referring to infrastructure improvements such as new roads and bridges. “When he goes into the voting booth, he’s not going to tell his buddies who he’s voting for but don’t be surprised.”

But the expectation that Blacks can counter voter suppression by turning out in record numbers amounts to a cruel double standard, Michael Arceneaux argued in a recent column for The Week entitled, “Biden’s voting rights betrayal.”

“White voters are never asked to ‘out-organize vote suppression,” he wrote.

Why the time is never ‘right’ for a voting rights bill

As I hear Democratic leaders rationalize why now is the wrong time to get rid of the filibuster or push aggressively for voting rights, a question comes to my mind:

When did White political allies of Black people ever say the time was “right” for us to demand our equal rights?

The time wasn’t right to reclaim Black voting rights in the South until Americans were horrified by images of White state troopers beating marchers in Selma in 1965.

The time wasn’t right to press for police reforms until Americans were horrified by the video of George Floyd being murdered on camera in 2020.

The time isn’t right to get rid of the filibuster and pass a new voting rights bill now, even though a recent Pew Research Center survey revealed that 48% of White Americans now say that voting is a “privilege,” not a right.

Politics, it’s been said, is the art of the possible. But determined political leaders can often make things happen if they’re passionate enough.

The Democratic Party used to know this.

When a senator warned President Lyndon Johnson that if he pushed for the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act the Democratic Party would “lose the South forever,” Johnson’s response was resolute, according to a passage in historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book, “Leadership In Turbulent Times.”

“You may be right,” Johnson said. “But if that’s the price I’ve gotta pay, I’m going to gladly do it.”

When it seemed like the passage of Obamacare was doomed, Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi told a nervous Democratic leader who wanted to pursue a less ambitious health plan focused on children that she wasn’t going to settle for “kiddie-care.”

There are some issues that are so fundamental to a party’s identity and survival that there is no middle ground, no way to finesse a hard choice.

As one voting rights activists recently tweeted: “I am uncompromising on voting rights because there is no middle point between the arsonist and the fireman.”

Black voters like Henry Adams, the courageous soldier who tried to organize Black voters in the South, had that attitude. But their White political allies took their vote for granted and treated them, in the words of Frederick Douglass, like “field hands.”

If the Biden administration doesn’t pass a new voting rights bill after Black voters help give them the White House and control of Congress, the sense of jubilation I witnessed firsthand in Georgia will evaporate.

And if more White Americans continue to regard voting as a privilege rather than a fundamental right, more Black voters will ask Democratic leaders a variation of a question that was first posed by their ancestors in the Jim Crow South:

What’s the use of building a new bridge or road when you don’t protect the voting rights of those people who gave you the power to do so in the first place?