When China announced it had inked a security pact with a tiny Pacific island nation this week, there was little fanfare – at least from Beijing.

As China put it, it was a mutually beneficial agreement aimed at creating peace and stability in the Solomon Islands, a country with a population less than half the size of Manhattan that was rocked by violent protests last year.

But other countries saw it differently.

To Australia, New Zealand and the United States, it was Beijing’s latest power play in an ongoing struggle for influence in the Pacific – a move that some claim threatens the very stability of the region.

Speculation had mounted over what would be in the agreement after an unverified leaked draft of the deal appeared online last month.

Some were concerned the agreement could see Canberra’s worst fear realized: a Chinese military base being built in the Solomon Islands, a first for China in the Pacific. Australia and the US were so worried that they sent delegations to the Pacific island, hoping to stop the agreement.

But China announced the deal had been signed on Tuesday, before the US delegation even had a chance to touch down.

Though details of the final agreement haven’t been released, some onlookers say the agreement makes Australia less safe and threatens to further destabilize the Solomon Islands, where there’s already been backlash over the government’s close relationship with Beijing.

But beyond the political and security fears, experts say the situation is a reality check for Australia and its partners that they need to adopt a different approach to China’s rising influence.

“Australia and the United States still haven’t woken up to the reality of Chinese power and how we’re going to deal with it,” said Hugh White, an emeritus professor of strategic studies at Australian National University, who previously worked as a senior adviser to the Australian defense minister and prime minister. “In both Canberra and Washington, they think that somehow we can make China go away, put China back in its box.”

How the pact came about

Concerns over the pact had been swirling for weeks.

According to a leaked draft document – which CNN has not been able to verify – the Solomons would have the ability to request police or military personnel from China to maintain social order or help with disaster relief.

The agreement appeared to relate to violent protests that rocked the country’s capital Honiara in November last year that were partly sparked by anger over the government’s decision to cut ties with Taiwan and switch allegiance to Beijing.

Protesters targeted parts of Honiara’s Chinatown, prompting Sogavare to request help from Australia under a bilateral security treaty the two countries signed in 2017.

From the Solomon Islands’ perspective, the separate agreement with China may have appealed, as it allowed the country to diversify its security relationship and leverage political posturing in the region, said Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, a political scientist at the University of Hawaii who hails from the Solomon Islands.

But others worry the agreement could be the first stage in a bigger plan – to establish a permanent Chinese military presence on the islands.

The reaction to Tuesday’s announcement of a signed pact was swift.

In a joint statement, the US, Japan, Australia and New Zealand said the pact poses “serious risks to a free and open Indo-Pacific.”

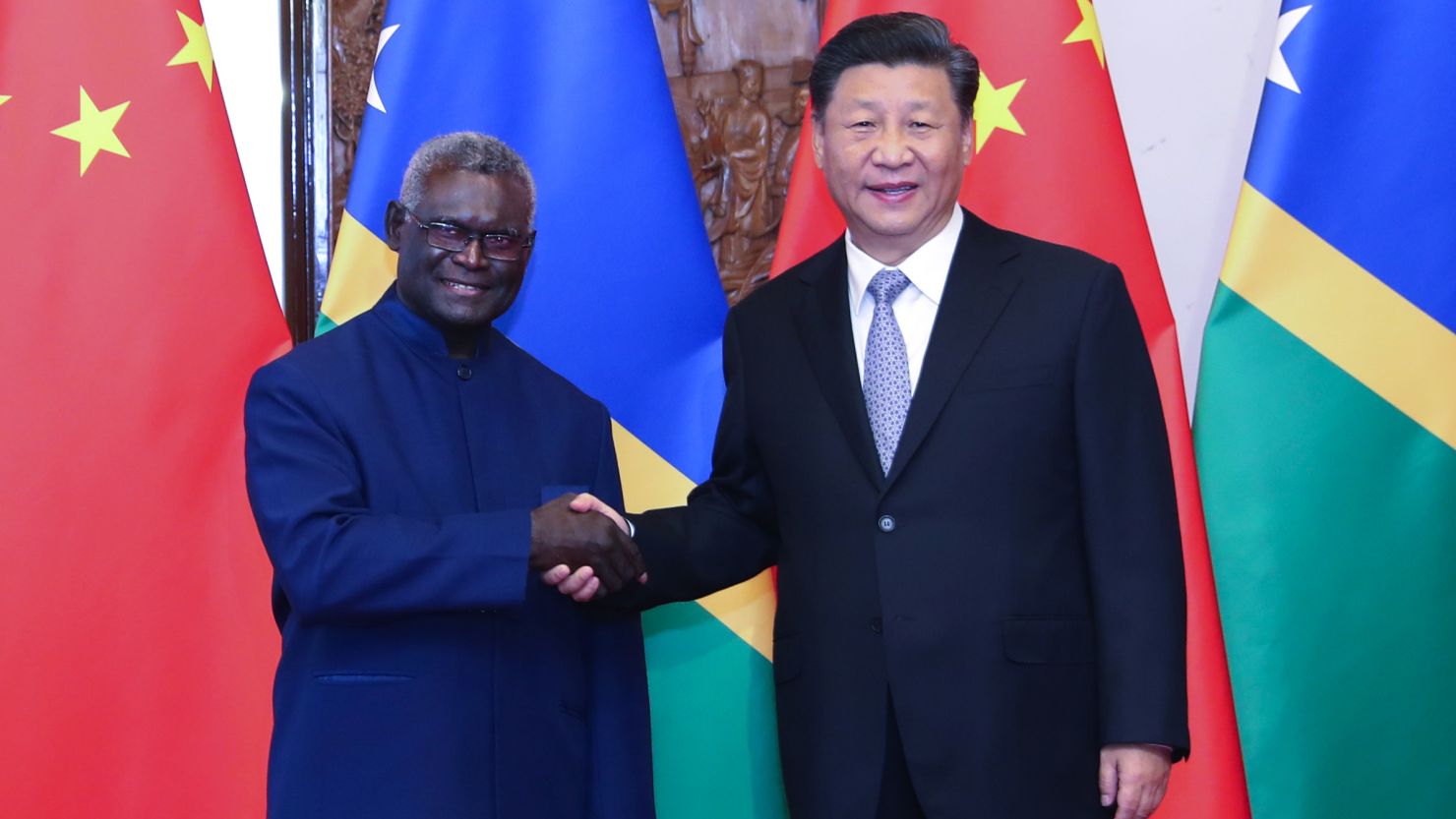

Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare insisted Wednesday the agreement doesn’t include permission for China to establish a military base, and urged critics to respect the country’s sovereign interests. “We entered into an arrangement with China with our eyes wide open, guided by our national interests,” he said.

Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin stressed that the “open, transparent and inclusive” agreement doesn’t “target any third party.”

But despite the reassurances, there’s still little detail about what’s been signed – and onlookers say that in itself is worrying.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know about what the agreement itself actually says, and also about what it will lead to,” said Australian National University’s White.

Political scientist Kabutaulaka said he thought it was unlikely China would build a conventional military base in the Solomons because it would create a lot of “negative publicity” for Beijing, inside and outside the island nation.

But experts say that doesn’t mean China won’t have a military presence on the island – of some form.

If China does have the ability to bring ships and military personnel to the Solomons as the unverified draft document laid out, then there’s no real need for a physical military base, Kabutaulaka said.

Mihai Sora, an expert in Australian foreign policy in the Pacific at Australian think tank the Lowy Institute, pointed to Djibouti as a country that signed a security agreement that evolved into a naval base that Beijing refers to as a logistics facility.

The prospect of a Chinese base in the Pacific is unsettling for the US, which also has military bases in the region that are becoming more strategically important as China expands its military presence in the South China Sea. It’s also unsettling for Australia, which potentially faces the prospect of Chinese ships docking not far from home – the Solomons is around 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from Australia’s northeastern coast.

“It’s probably true that it would mean Australia is less secure as a result of this agreement,” Kabutaulaka said.

But, says White, a Chinese military base in the tiny nation only becomes a real issue for Australia during any potential conflict with China. The significance of any base hinges on how well Australia manages its relationship with China – a relationship that’s become increasingly fraught in recent years.

“In practical terms … I don’t think that does nearly as much damage to Australia’s security as a lot of other people do,” White said. “It is a significant issue if we find ourselves in a major war.”

What the future holds

The lack of public detail about what’s in the pact is not only concerning for the Solomon Islands’ international partners. Inside the small nation, uncertainty about what it contains has already prompted criticism.

“It’s clear to me that the vast majority of ordinary Solomon islanders do not want a base here, or even this deal. A majority do not want China here at all in the first place,” the nation’s opposition leader, Matthew Wale, told Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s The Strategist.

Some have suggested the deal itself could exacerbate tensions between those who support closer China ties and those who do not.

“The discourse about geopolitical competition is creating divisions that could become domestically troubling,” said Kabutaulaka.

“There is also a need for the international community, and for Solomon Islanders in particular, to look at the challenges internally that then created the kinds of things we saw in November of last year, that then in turn created the need for Solomon Islands to sign the security agreement with China.”

Those challenges include economic inequality between islanders, with some taking their anger out on Chinese businesses they see as a symbol of closer ties with the mainland.

But the agreement also sends a much bigger message: that Australia and its allies’ approaches in the region isn’t working.

Australia has long talked up the idea of the “Pacific family.” But according to White, Australia pays little attention to the Pacific unless there’s questions about security. And more than that, Australia and its allies are still stuck in the past, imagining that China’s power can be minimized and those countries can remain the dominant powers in the region, he said.

“More and more over the last few years, Australia has found itself moving to a position where our approach to managing the rise of China is to try and stop it happening,” he said. “That’s not going to work. Australia has to learn to live with Chinese power – and that includes Chinese expanded influence in the southwest Pacific.”

“It just poses a challenge to us to lift our game to maintain our influence there – and that’s something we should be doing anyway.”