The image of a typical American cowboy – a rough-hewn white guy in dirt stained blue jeans, cowboy hat and boots – is a staple of Western movies and modern country music. But as icons go, it gives an incomplete picture.

While many cowboys on the American frontier in the 19th century were black – as many as one in four, by some estimates – their presence in history and within the cowboy community today is hardly recognized. A handful of movies have featured black cowboys in the Wild West, including Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained” and Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven,” and some black cowboys, notably Bill Pickett in the 1900s, became popular rodeo stars. Otherwise, black cowboys are rarely depicted in art or popular culture.

“History shows us that in the late 1860s blacks made up about 20 percent of the US population, which coincides with the whole frontier movement. In fact, many newly emancipated blacks did move west in search of new opportunities in a post-antebellum America,” wrote Dr Artel Great, a historian of black cinema and film studies professor at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington. “Many of them were skilled ranch-hands with vast experience in agricultural labor – a requirement for surviving life as a cowboy.”

However, Hollywood has mostly offered a whitewashed narrative. As Great explained, the western film is a classic in American culture, so the erasure of black cowboys from pop culture is linked to “the tension between who can and cannot participate in the fruits of the American dream.”

The cowboy culture of the Mississippi Delta

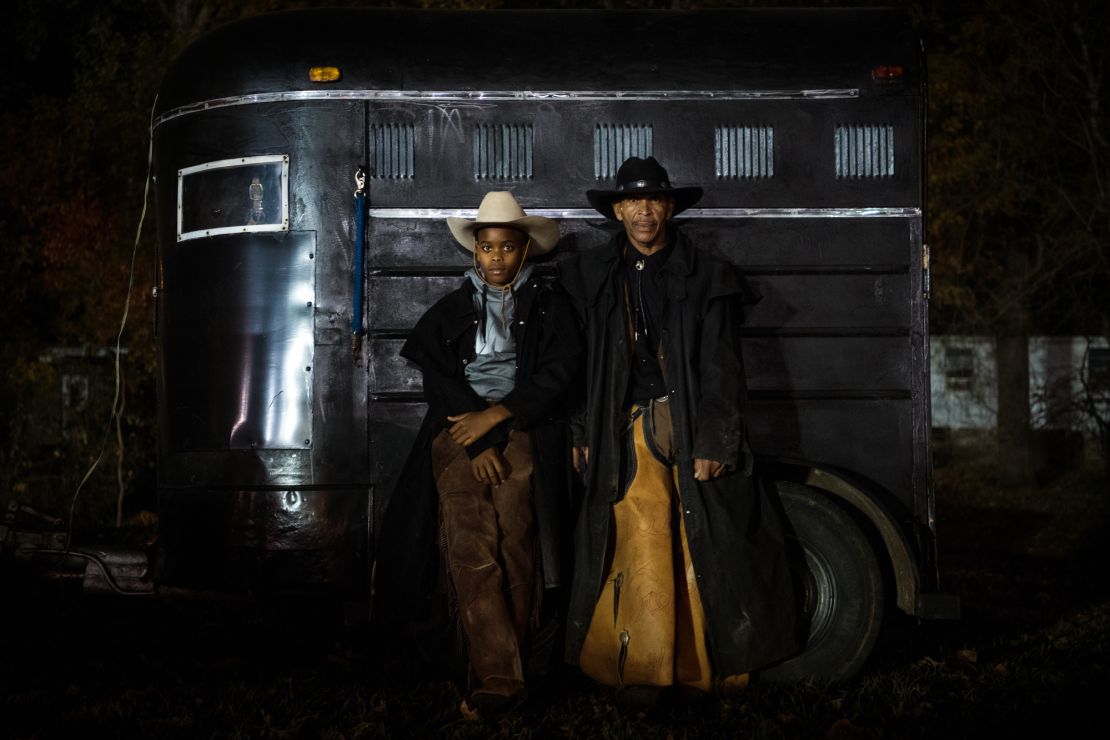

Photographer Rory Doyle’s ongoing project “Delta Hill Riders” aims to tell a more realistic and diverse story about black cowboys today by focusing on African-American cowboys and cowgirls in the Mississippi Delta, a flat farming region in the deep South between Memphis, Tennessee, and Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The collection of images, all shot in the Mississippi Delta – where, according to Doyle, a large concentration of black cowboys and cowgirls reside today – has won several awards, including the recent 16th Annual Smithsonian Photo Contest.

Through his research, Doyle said in a phone interview, he found little historical photographic documentation of black cowboys in the United States. It is, he explained, a part of history that has been overlooked. “(Members of the black cowboy community) will tell you, ‘This is what we’ve always done. My dad did it. This is how I identify.’”

Doyle, who is originally from Maine, moved to Cleveland, Mississippi, in 2009. He first saw black cowboys and cowgirls riding in the city’s Christmas parade in 2016. “My first thought was, ‘There’s a lot more diversity in cowboy culture than I realized, and there’s a story here,’” he said.

Over time, Doyle immersed himself in the culture by talking with riders as they groomed and cared for their horses, visiting them in their homes and accompanying them on trail rides and to area rodeos. He became such a fixture that he was eventually made an honorary member of the group after which his photo series is named, the Delta Hill Riders.

Doyle has photographed the cowboys and cowgirls in a variety of settings, including at social gatherings at a rural nightclub. While his intimate photos offer hints of what many would expect to see – denim, cowboy hats and horses – the fly-on-the-wall-images also tell a different story. One photo shows a group of boys hanging around outside a McDonald’s, while another features a bare thigh, revealing a large tattoo.

Passing on a legacy

Doyle has shown his photos in New York City and London, but his favorite exhibition was at home in Cleveland. Opening night drew a large crowd, including many of the riders in his photos.

“It was packed, and really diverse, which is not always the case in the Delta,” Doyle said. “And it gave the cowboys a platform to speak, to share their voice.”

Peggy Smith, an African- American cowgirl who appears in many of Doyle’s photos, said she knows of no famous riders who look like her and her friends, which is one reason she’s happy to be featured in Doyle’s photos with her horse, Jake.

At 53, she recalled learning the ropes early in her childhood. “My father used a horse to work his farm, and he taught his children to ride – I’ve been riding since I was 12 years old,” she said over the phone. According to Smith, being a cowboy or cowgirl is more of a hobby these days, centered on rodeos, parades and trail rides in Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama and Tennessee. “It’s funny. When we go somewhere, people are always just talking about the cowboys,” Smith said. “And I say, ‘Wait a minute, the cowboys ain’t the only ones doing their thing.’”

Lawrence Robinson, who goes by “Cowboy,” is, at 65-years-old, one of the last working cowboys in the hills near the town of Bolton, Mississippi. “I started riding my father’s horse when I was about 15 years old,” he said in a phone interview.

Three years later, in 1972, he got a job as a cowboy on the Bolton area farm where he still works.

Robinson is proud of his cowboy status. “Most of them now is imitation cowboys. I’m a real one. My daddy had horses and mules back in the day, for farming, and I’d ride them. They couldn’t get me off. When I was about 17, I bought myself a Shetland pony and the first thing I caught was a goat.”

Robinson, who still rounds up cattle on horseback, said he is glad to see people riding horses, even if it’s for recreation rather than work. He also enjoys sharing his riding skills.

“I’m trying to get some young boys stirred up,” he said. “All I can say is, they’re still out there, trying to do their thing on a horse.”