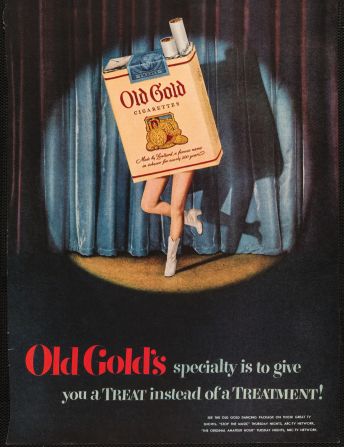

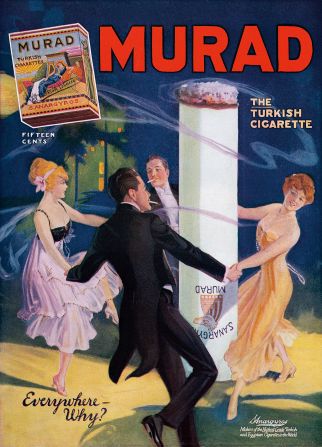

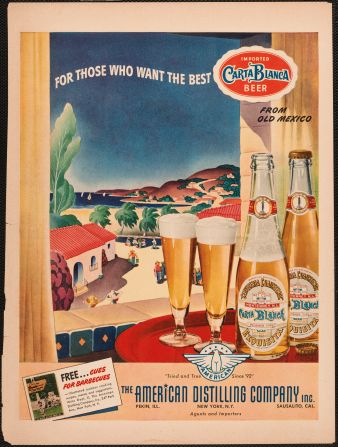

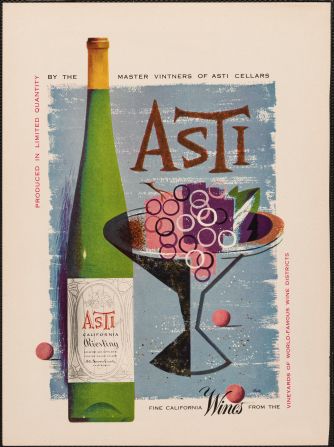

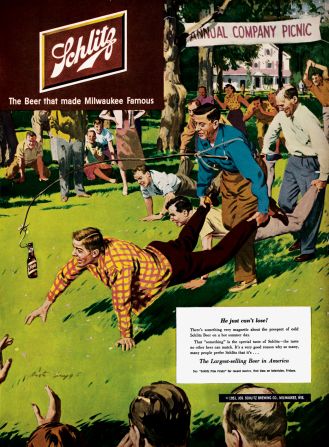

There was a time in advertising when tobacco was sold as a nerve-calming, throat-soothing agent, and alcohol as an elixir for social success.

Even doctors were involved – not to warn about the health risks, but to sell the product. One campaign for Camel with the slogan “More doctors smoke Camel than any other brand” ran for eight years from 1946, both on TV and in the journal of the American Medical Association. The doctors were actors and the data was based on unofficial surveys conducted by the advertising agency, but the message stuck.

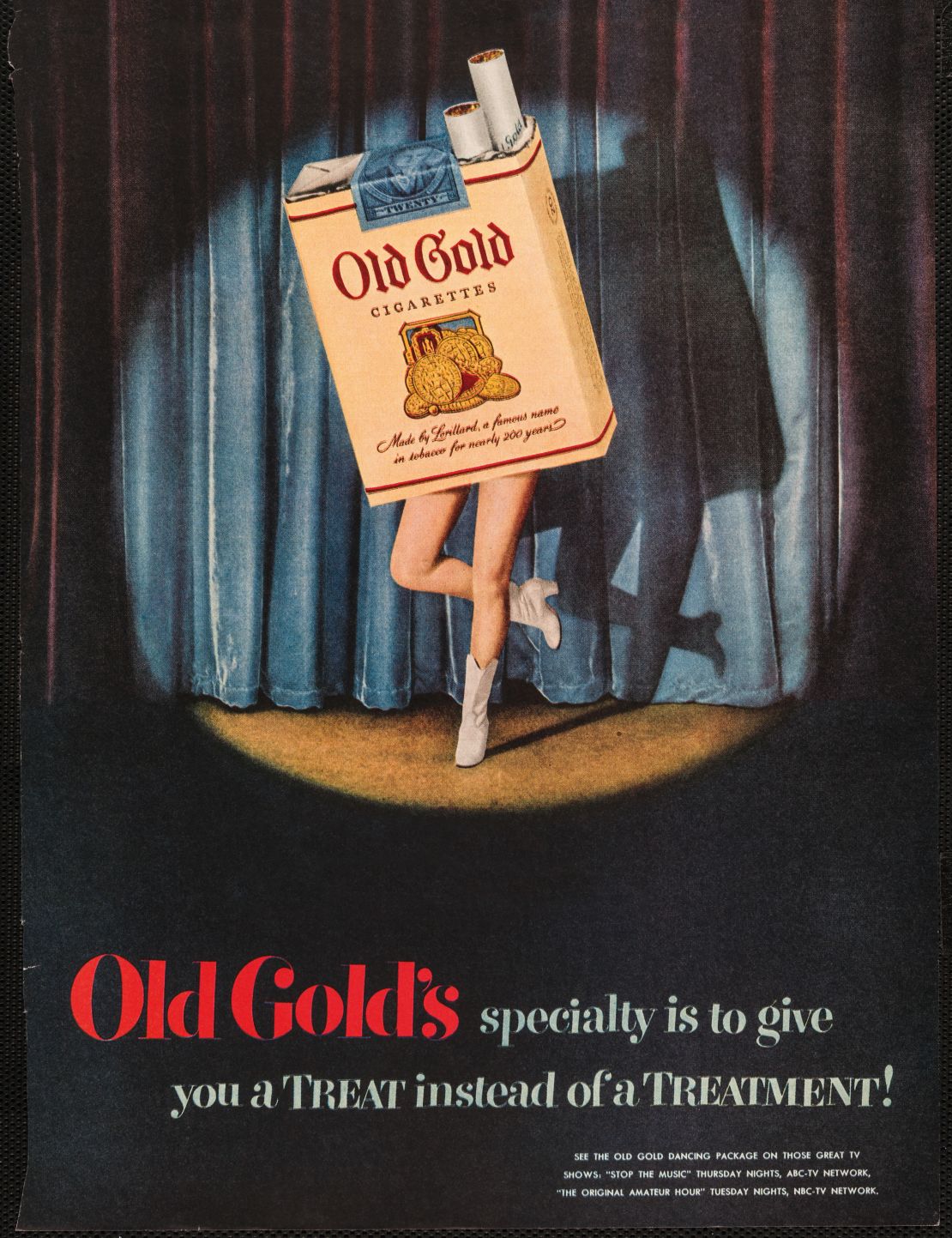

“The negative health aspect of smoking is never there, it was always something very positive,” said Jim Heimann, author of “20th Century Alcohol & Tobacco Ads,” during a phone interview. “In fact, they were touting the health benefits of smoking. Anything health related doesn’t really come into play at all until the 1960s.”

In 1958, just 48% of Americans believed that smoking caused cancer. But a decade later, in 1968, the figure had jumped to 78%, according to US National Library of Medicine.

A world of endorsements

In these early colorful ads, almost always made with illustrations rather than photographs, cigarettes are presented with words like “fresh” or “mild” and endorsed by well-known public figures like Marlene Dietrich, Bing Crosby, Ronald Reagan, Barbara Stanwyck, Spencer Tracy, Frank Sinatra and John Wayne, who subsequently blamed his habit for the cancer that took one of his lungs in 1964. He died of another stomach cancer in 1979.

Other endorsers included musicians, cartoon characters, Santa and even babies, as seen in a particularly worrisome set of 1950s ads where infants are recite lines like “Before you scold me, Mom … Maybe you better light up a Marlboro.”

“I think they just saw it as being a novel and humorous approach to smoking, because at that time it was totally acceptable. It was just part of the fabric of American culture and even the rest of the world had accepted the idea of smoking as being part of daily life,” said Heimann.

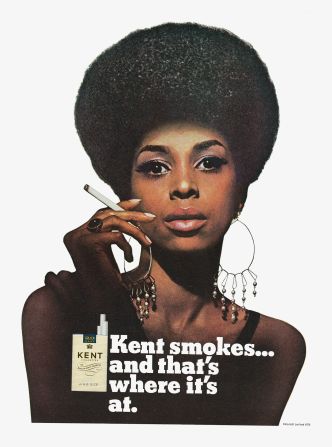

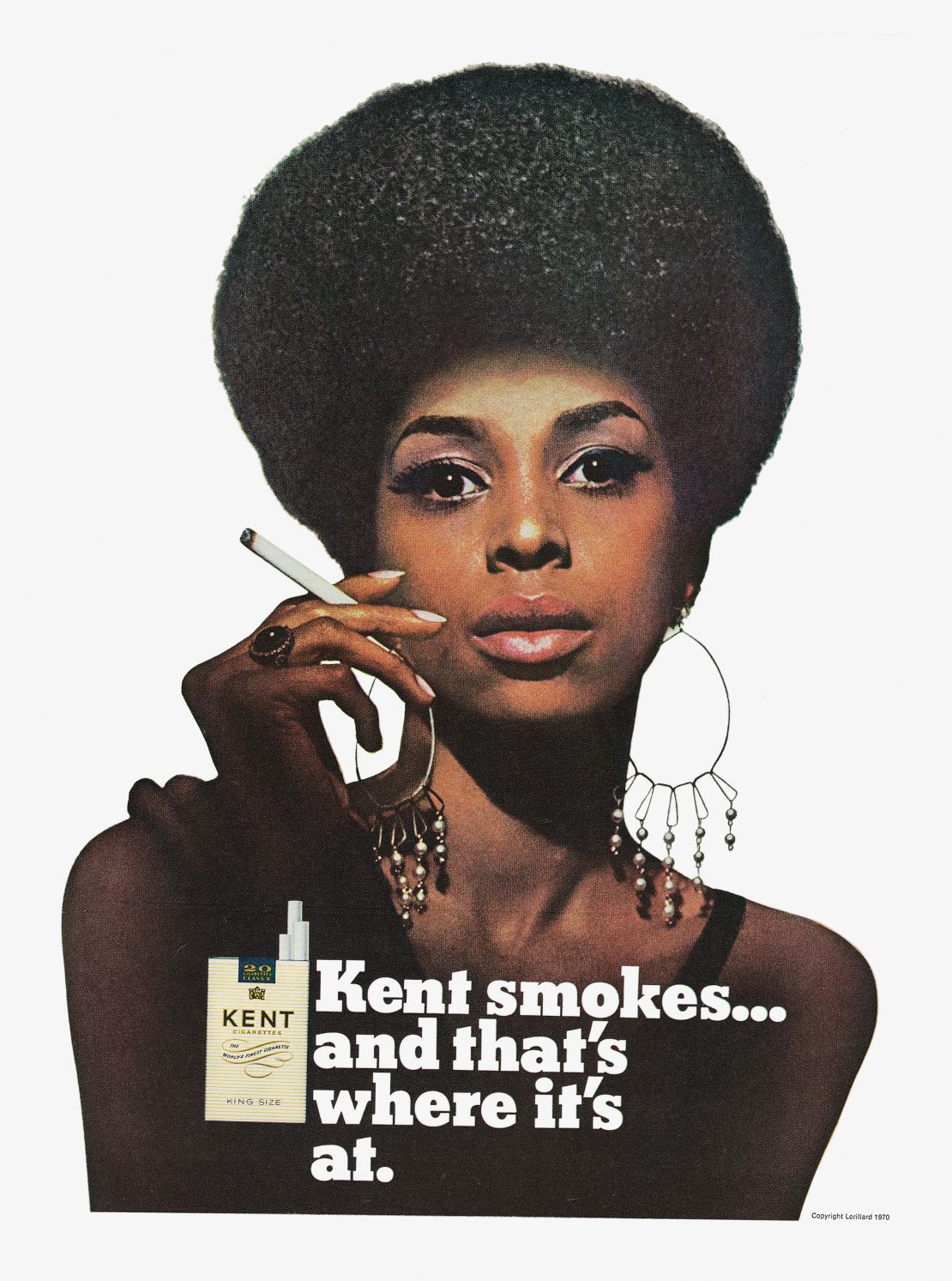

Notably, early ads lacked any trace of racial diversity.

“You don’t see minorities at all – it’s basically a white person’s world until the late 1950s and then the mid-1960s, when things began to change as social mores change.”

The switch to lifestyle

“Even when the health implications (of smoking) became known, to a degree things stayed the same, just more nuanced. It’s only when the government began to extend its control over the advertising that things really change,” Heimann said.

Starting in 1971, TV and radio ads for cigarettes were banned, and the industry moved wholesale to magazines, newspapers and banners. But the tighter control meant that positive messages highlighting the product itself would no longer be allowed.

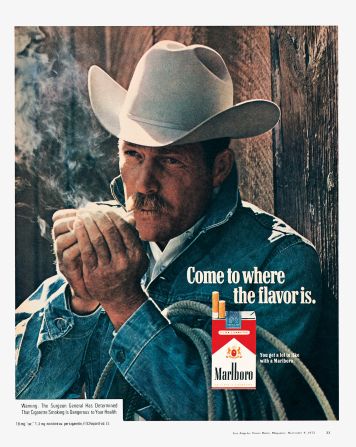

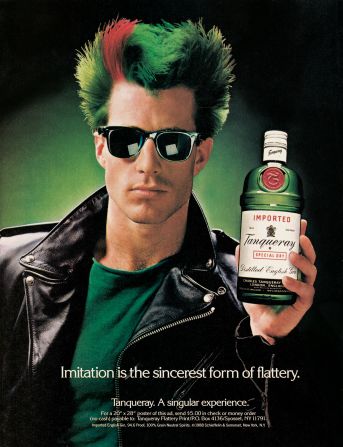

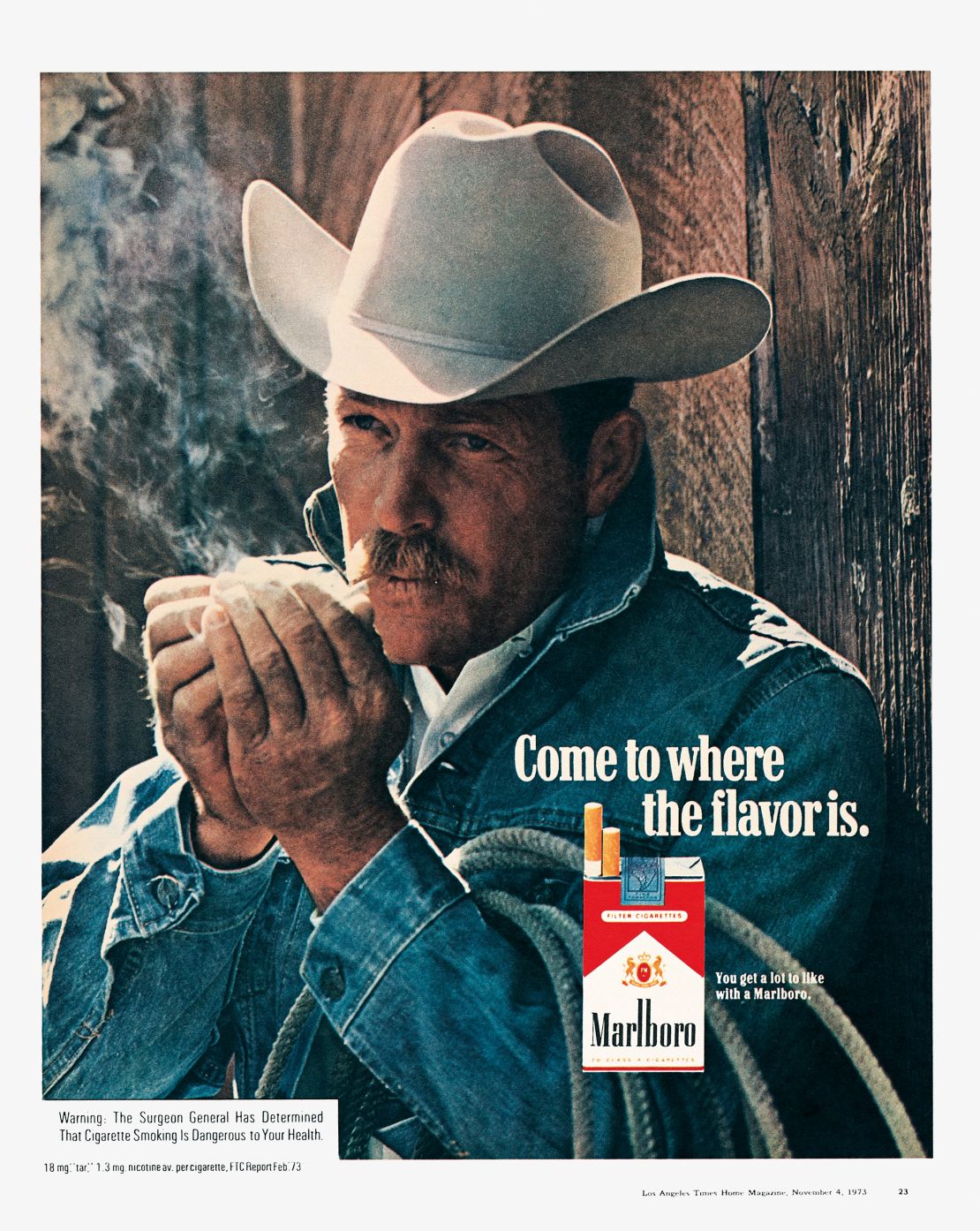

The theme of the ads pivoted to lifestyle, bridging the gap between tobacco and alcohol, which had always been associated with glamorous and adventurous endeavors. The general design, partly as a consequence, switched from illustrations to photography.

As a result of these changes, the Marlboro Man, probably the most famous smoker in the world, achieves universal notoriety. Its reference to simple, beloved themes of freedom and the Wild West make the character so iconic that it becomes an instantly recognizable substitute for the product itself.

“Once the government started clamping down on how cigarette smoking was portrayed in the 1970s and into the 1980s, the Marlboro Man was so established that ads didn’t even need to show cigarettes. Just showing four horses and the Marlboro logo was enough,” said Heimann.

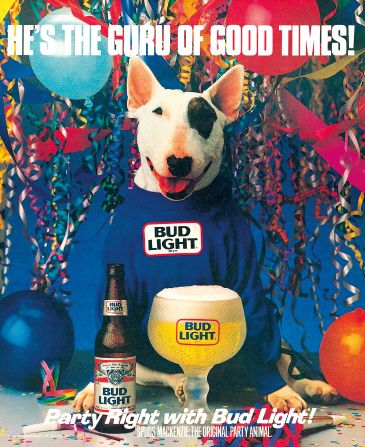

(Similarly conceived was Spuds McKenzie, a bull terrier who debuted as a mascot for Bud Light beer in a 1987 Super Bowl ad, and became so popular that he inspired merchandise of his own.)

Things changed radically in 1998 with the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, an accord between most US states and the five largest tobacco manufacturers that severely curtailed the marketing and advertising practices for cigarettes, and halted the use of mascots, recognized as mere tools to target a younger audience. The Marlboro Man made his last appearance in 1999, when his remaining billboards were taken down across the country.

“20th Century Alcohol & Tobacco Ads” by Jim Heimann, published by Taschen, is available now.