Story highlights

How do you communicate great architecture to someone who can't visit the building?

Today, many photographers try to capture more than just the bricks and mortar

CNN talks to Iwan Baan, the biggest star in the field, and the overall winner at the Architectural Photography Awards

From Stonehenge and royal palaces to the skyscrapers that define a modern city’s skyline, great building can encapsulate their eras.

“Every great architect is – necessarily – a great poet”, said legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright. “He must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age.”

But unlike poetry, buildings struggle to travel. When the work is many stories high and forged from concrete and glass, disseminating its era-defining genius requires something a little more lightweight.

The annual Arcaid Images Architectural Photography Awards champion artists who “translate the sophistication of architecture into a readable and understandable two dimensions, to explain and extol the character, detail and environment of the project”.

The Portuguese photographer Fernando Guerra was this year’s overall winner with his image of Richter Dahl Rocha & Associés’ EPFL Quartier Nord in Ecublens, Switzerland. Shot at dusk, the picture is a mesmerizing collation of color, light and people – portraying a structure alive and in motion.

“I was waiting all day,” Guerra remembers. “Five minutes before I took it, the place was completely empty because everyone was inside their quarters watching the football and I was just cursing the silence. But then suddenly the match ended and everybody came out and I got it. I didn’t think about the photo for some time, it was only after I edited the work that I saw I had something special.”

Over the years, important partnerships have sprung up between architect and photographer, such as that of Le Corbusier and Lucien Hervé. Inspired by avant-garde artists like Mondrian, Hervé rejected the tradition of taking wide shots of a building, instead fashioning flowing, yet abstracted, series that focused on the details. The results were cinematic: an emotional journey through a building, rather than simply a standpoint outside it. Le Corbusier was rapt – he described Hervé as having the soul of an architect, and often changed his plans in response to his work.

California’s Julius Schulman was undoubtedly one of the biggest names in the field. His images of houses by Frank Lloyd Wright, John Lautner, Richard Neutra and, perhaps most famously, Case Study House #22 by Pierre Koenig, not only helped forge those architect’s careers, but became the visual language for the post-war resurgence of the American dream. His photograph of Koenig’s house created an instant mythology that lasts to this day – it was 1959 in Los Angeles, the city of angels, the future, opportunity, hope. But it was also a cause of conflict. Koenig believed the picture had transcended the architecture it portrayed, his reputation as an architect being subsumed by Shulman’s as an artist.

Today’s most heralded: Iwan Baan

In architectural photography, as with all forms of art, fashions change. Back in the 50s, Shulman was one of the first to position people inside buildings to create a sense of the ongoing life of a house, but in the 80s and 90s, people were banished in favour of a vision of buildings as clean, crisp and uninhabited. Today, Iwan Baan is at the vanguard of yet another sea change. He is probably the most famous in the field, but Baan dislikes the description “architectural photographer”.

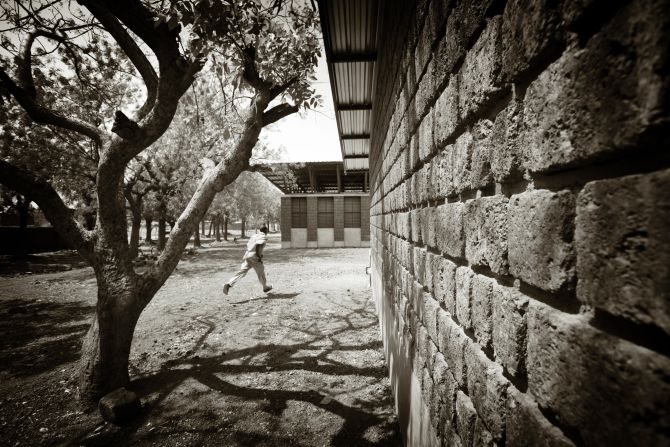

“A lot of architectural photography is just describing architectural details, showing a building isolated from its surroundings, stripped of its sense of people, of the references that bring it back to a specific moment in time,” says the Dutch photographer.

Shooting for international architecture firms OMA, Herzog & de Meuron, Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid, 40-year-old Baan has developed a richly textured style that embraces all elements of a building’s situation into his pictures, particularly the people. “The projects I am really interested in have a certain urgency and a need to be in a specific place.”

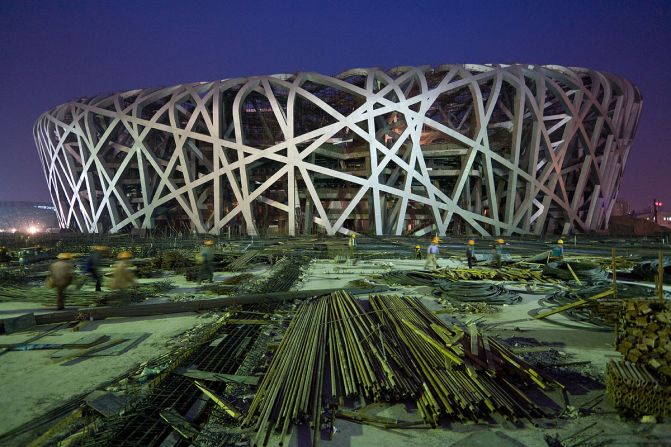

For the past decade, Baan has been working on Koolhaas’ construction of the CCTV tower in Beijing. “At moments you have 10,000 workers on site, who also live there, so it’s all a sort of informal village around it of people who come from the countryside and build this massive new building.”

The result – ongoing as the building isn’t yet finished – is as much a work of anthropology and politics as architectural photography. “A place like Beijing is changing so incredibly fast, so it’s a view of the whole environment and the perception of people in that place. My mission is not just a look at the building and the architecture, but a look at the world around it, which is changing at the same speed, and is really fascinating.”