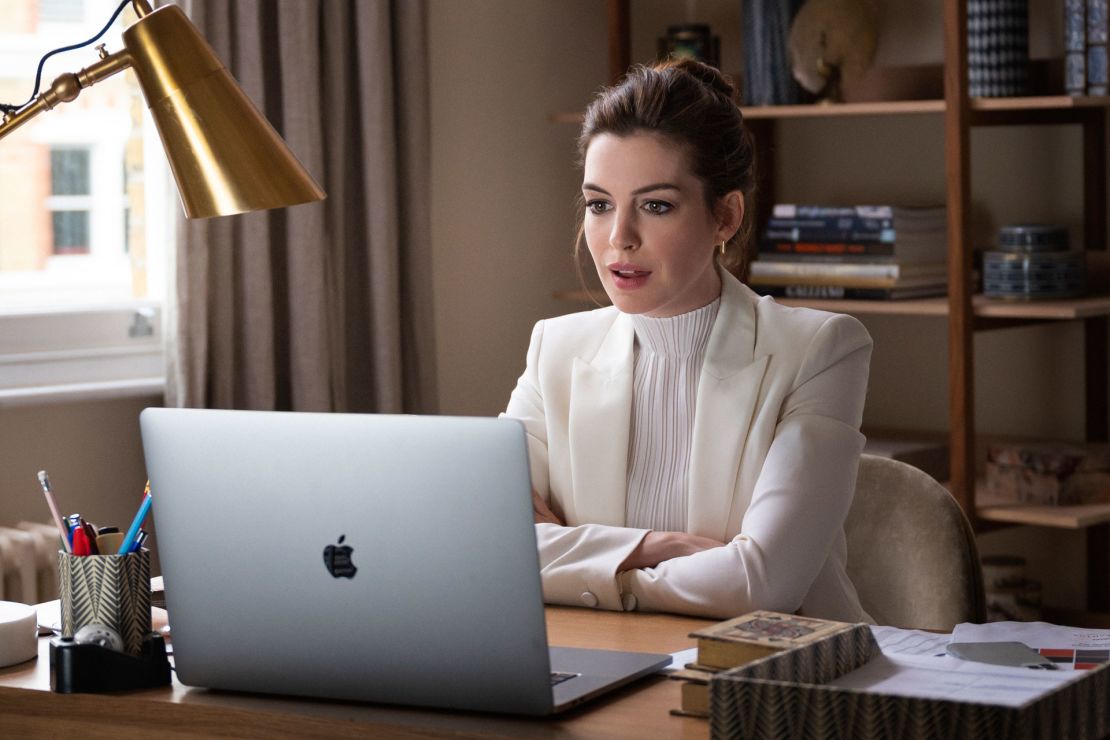

When “Locked Down” premiered in January, it provoked eye rolls from critics. Telling the story of a couple whose imminent separation is put on hold by a stay-at-home order, it was among the first movies to be entirely written and filmed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

As its title suggests, the story addressed contemporary struggles. But detractors posited that the film missed an opportunity to explore the shared anxieties of nationwide lockdowns, while others conceded that it might have been better received with the benefit of several years’ hindsight.

When the project was first announced, the pandemic had been raging for months though vaccinations were still a distant dream. The story of a relationship tested through a mandatory stay-at-home order might have seemed, from a studio perspective, like a no-brainer: Of course people could relate to it.

But for audiences that may have been part of the problem, according to Karen Dill-Shackleford, a social psychologist at Fielding Graduate University and editor of the journal Psychology of Popular Media.

“There are two ways of coping with trauma: active and passive coping,” said Dill-Shackleford. “Some people like to engage more with the news surrounding the pandemic because it makes them feel as though they have some control over it. Others cope through avoidance, and for them escapism is key.”

Crucially, however, there is no single type of story audiences want to watch, she added. “We have different needs depending on our lived experiences, and those needs also change as we process our trauma.”

Throughout the early months of the pandemic in the US, many viewers gravitated towards shows and movies they had seen before. “People don’t want any surprises in the media they consume when they have enough uncertainty in their daily lives,” Dill-Shackleford explained. “They need to know that everything turns out OK in the end.”

Inundated with daily updates about case numbers, hospitalizations and deaths, some people may have found comfort in re-watching shows because they didn’t need to pay close attention to what was happening on screen, Dill-Shackleford added. When reality demands our constant concern, it may be comforting to disengage from the outside world and let our minds amble through a story about mask-less teenagers finding a prom date.

At the other end of the spectrum, however, plenty of viewers were seeking out depictions of fictional pandemics. As the virus cases surged across Europe and closed in on the US in the first months of 2020, so too did downloads and streams of 2011’s “Contagion,” a movie about an American woman who returns from a trip to Hong Kong as the unknowing carrier of a novel respiratory virus. By mid-March, shortly after the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a pandemic, “Outbreak” (which portrays the rush to contain a fictional, ebola-like virus in California) became the ninth most popular movie on Netflix in the US.

Erase or embrace?

This bifurcated approach to media consumption may have left storytellers unsure of whether – or to what degree – they should broach the social, financial and physical issues surrounding the pandemic. Should they lean into the trauma by offering comfort and solidarity to viewers, or should they ignore the pandemic completely by depicting an alternate reality in which the terms “social distancing,” “lockdown,” and “essential worker” had never entered the mainstream lexicon?

The answer, according to Dill-Shackleford, is a resounding “it depends.”

“The decisions to portray the pandemic on screen are more intense than other storytelling decisions,” she said. “Writers and directors don’t know which part of their audience they’re providing a service for and which part of their audience can’t bring themselves to watch.”

This isn’t the first time studios have faced such quandaries in the wake of a deadly event – and their approaches have varied. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for instance, manifested in Ishiro Honda’s 1954 film “Godzilla” as a creature that wreaks havoc on helpless citizens. Rather than shying away from fears of nuclear holocaust, the movie reflected Japanese anxiety around nuclear destruction.

Conversely, after 9/11 many US storytellers avoided tackling the tragedy head-on. Several TV shows that were set in or around New York, like “Sex and the City,” and “The Sopranos,” simply removed the World Trade Center from their opening credits following the attacks rather than examining the impact it might have had on the characters’ lives.

Some shows have taken a similar approach to Covid-19. The new “Gossip Girl” reboot, for instance, began filming last November, though Covid-19 appears to have been eradicated in the fictionalized New York City in which the story is set.

But series revolving around frontline healthcare workers and grocery store employees, like “Grey’s Anatomy” and “Superstore,” clearly felt more obligated to portray their experiences on-screen. One of the most prominent examples of pandemic storytelling came from season seven of ABC’s comedy “Black-ish,” which explored the ways Covid-19 affected members of the Johnson family as they work, attend school (via Zoom) and live in close proximity to one another.

At one point, father Dre (Anthony Anderson) slumps down on the couch and admits that he’s been feeling irritable and anxious, complaining that “nothing feels normal.” His anesthesiologist wife, Rainbow (Tracee Ellis Ross), shakes her head sympathetically and responds, “Nothing is normal, Dre. We’re disinfecting boxes … I microwaved our mail yesterday. So it’s understandable that you’re stressed, sweetie. We don’t have any of our normal coping mechanisms … We’re used to living life with certainty and we don’t have that anymore.”

Dill-Shackleford said that this type of on-screen exchange demonstrates the therapeutic potential of media. “In many ways – and especially as we are struggling in the moment – we rely on these stories to make us feel as if we’re not alone,” she said.

Benefit of hindsight

At this stage in the pandemic, Dill-Shackleford said, depicting Covid-19 remains a double-edged sword. Even among viewers who are comfortable talking about the events of the past 18 months, there is “a certain level of exhaustion” with the topic.

“With some people (who are) becoming vaccinated and starting to slowly carve out a new normal, the last thing they want to do now is be reminded of the head space they were in a year ago,” Dill-Shackleford said.

For others, especially those living in areas with surging cases and hospitalizations, we are “still in the middle of death and disease” and “dealing with issues with vaccine hesitancy,” said Chrysalis Wright, the director of the Media & Migration Lab at the University of Central Florida. “Some people simply don’t have the distance,” she added, to “sit back and enjoy” a movie exploring these heavy themes.

Wright believes future renderings of the coronavirus pandemic should flesh out the nuances in how it affected different segments of our societies.

“When enough time has passed for us to reflect on this era, I would really like to see movies and television shows that take into account these experiences,” she said, adding that the impact of Covid-19 varies according to people’s backgrounds. “For example, show how the pandemic disproportionately affected Black Americans; discuss the increase in hate crimes towards Asian Americans.”

Those who went through particularly traumatic experiences, such as losing loved ones, losing a job or struggling with mental health issues, may naturally shy away from content that forces them to relive their ordeal. But, Wright said, the general public will benefit from having these stories produced for mass consumption.

“Even if you can’t stomach sitting through these movies or television shows, it’s critical for other people to be able to understand the far-reaching repercussions of the public health crisis from other perspectives,” she added. “Seeing different experiences represented on screen helps establish empathy between people of different backgrounds.”

As countries around the world attempt to restore a semblance of normalcy, audiences may also seek out narratives that showcase early pandemic experiences as a way of achieving closure, said Wright.

“If we see a character losing their job, struggling with working from home, or navigating remote learning, it validates us,” she explained. “If we didn’t do it perfectly, it’s fine because nobody did it perfectly.”

Regardless of viewers’ current media consumption habits, both Dill-Shackleford and Wright hope that future portrayals on the pandemic will inspire discourse about individual and collective experiences alike.

“If a show or movie chooses to address the pandemic, I hope they do so in a way that helps their audience think through the events they’ve lived through,” said Dill-Shackleford.

“There’s a bidirectional experience between ourselves and the media we consume,” added Wright. “Media reflects our experiences and, at the same time, it influences our behaviors and future experiences.”

Top image: Jude Law in the 2011 movie “Contagion.”