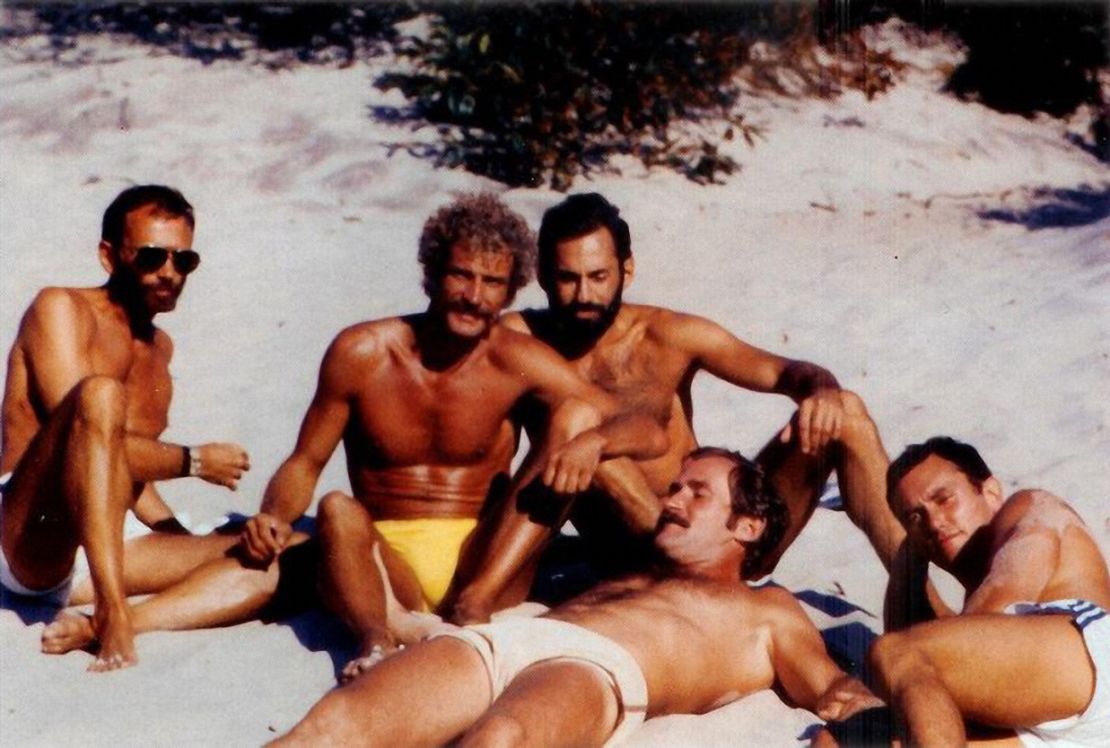

“Orgy is a grand old tradition of Fire Island,” wrote New York Magazine in 1972.

The Hamptons’ party-going cousin, south of Long Island, New York, didn’t earn its reputation for nothing. In the mid-twentieth century is was a place to see and be seen; a place where good times could be found, particularly for the sexually-liberated young man.

Fire Island Pines, its upmarket gay resort, hosted near-naked black tie galas and impromptu fashion shows by Diane von Furstenburg in its pomp. Calvin Klein called the Pines home and Truman Capote wrote “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” from one of its beach houses. At its peak, 1979’s “Party of the Century” was such a hot ticket even the owner of Studio 54 struggled to get in.

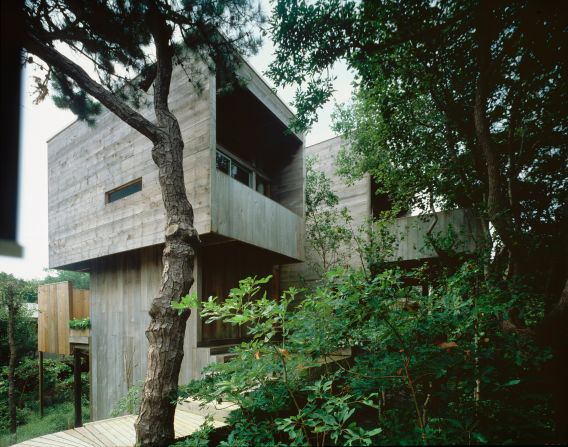

The island’s exploits from this era have since passed into legend. However, what lives on is its stunning architecture, built for the Pines’ tasteful and moneyed inhabitants. But with no protection from developers and suburban creep, can the party last for much longer?

The architecture of liberation

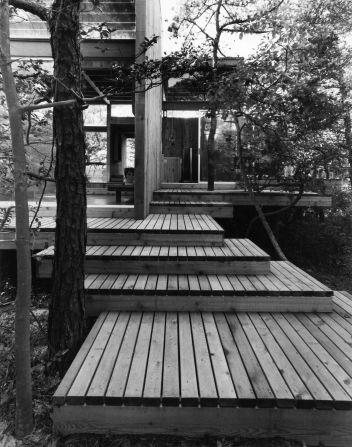

Fire Island Pines is a boon for Modern architecture enthusiasts, thanks largely to a small set of architects whose work remains largely under the radar.

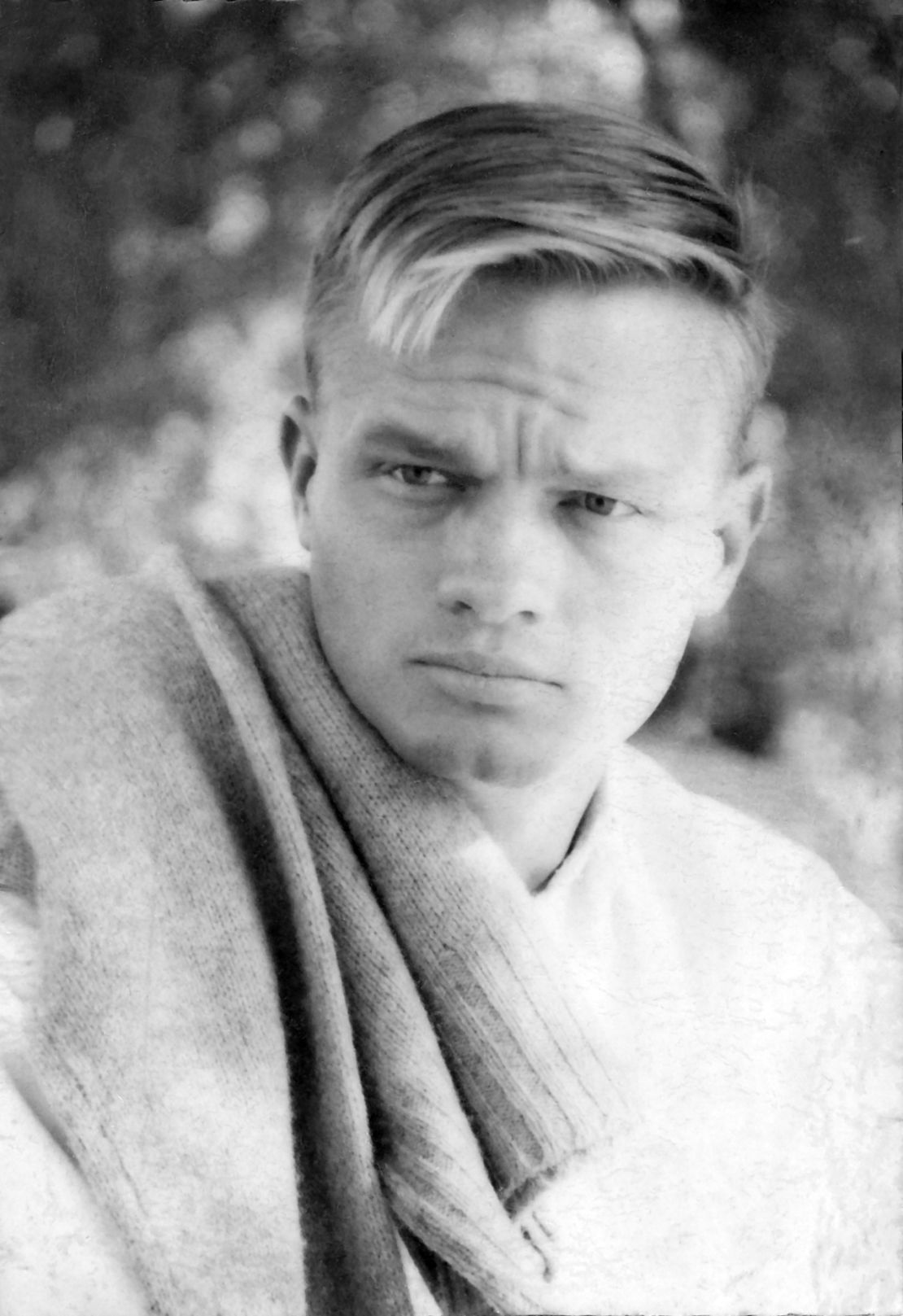

One of them was Horace Gifford, a young gay architect who came to Fire Island in 1961 with a talent for timber. At the time the Pines’ neighboring resort of Cherry Grove was the premiere destination for the gay community. But moving to the Grove came with a catch.

“[It] was already known as a gay destination,” explains Pines resident, architect and author Christopher Rawlins. “One could not claim an address there without being publicly identified as a homosexual.”

In the pre-Stonewall era many professional gay men moved into the Pines – ostensibly a family resort – settling surreptitiously in the late ’50s and ‘60s and keeping their sexuality out of the public domain. Designing many of their beach houses were Horace Gifford, Harry Bates and Canadian architect Arthur Erickson.

“[The houses] really trace the arc of gay liberation,” Rawlins argues. “They started out in many cases as these sort of enclosed compounds, which shielded the life within, because this was the early ’60s and a nominally heterosexual community.

“But once you get through to the Stonewall era and beyond they literally opened up. Rather than being protective compounds, they become more of an advertisement of the life within.”

These open beach houses were flooded with light from large windows. Bathrooms replaced mirrors with glass. Privacy and discretion were no longer such issues.

“I see the homes in almost anthropomorphic terms,” Rawlins suggests. He says the older working class resort of Cherry Grove with its curves and painted floors mimics its penchant for camp and drag. In comparison the Pines has a stripped-back aesthetic, reflecting the “muscular macho look that prevailed in the ’70s.”

That being said, there were softer touches within.

“The make-out loft entered the architectural lexicon via Horace Gifford,” argues Rawlins. In the early ’70s Gifford modified his own 1965 home, adding a sheepskin-lined love nest to his residence. Similar settings were put to good use in Wakefield Poole’s “Boys in the Sand” and the “porno chic” flicks of Richard Winger, where Fire Island’s architecture became as fetishized as the bronzed flesh on screen.

But for all their indulgences, these homes were constructed to showcase nature. Delicately poised on the cusp of the Atlantic, the architecture was informed by nature rather than imposing on it – an approach Rawlins suggests was ahead of its time.

The author recounts an anecdote from a party at Arthur Erikson’s house: At the stroke of midnight the ceiling retracted, releasing gold and silver balloons into a crisp starlit sky. “That was the sort of spectacle people wanted to create,” he says.

Embracing history

Speaking from the Pines, Rawlins, who has documented the island’s architecture in “Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction” and new interactive site PinesModern.org, says the resort has lived through dark times too.

“There’s absolutely a sense of nostalgia here,” he explains. “I think part of our culture’s love for a good time to a certain extent also speaks to an incredible amount of pain a number of us have experienced.”

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s did not leave the Pines unscathed.

“You’ve got to understand, a lot of these houses are shared, and so it’s not just a couple, or a person living in a house. It’s a smaller community living within a larger community. During the AIDS crisis entire houses perished.”

Of the original inhabitants of Rawlins’ home, only two now survive.

Like Rawlins, many of the Pines’ historic beach houses are inviting in a new generation of gay men, continuing a community of both young and old.

“I was lucky to be ‘adopted’ by a number of older gay friends who have lived proudly and generously, even as society looked down upon them,” he says. “Like many gay people I grew up without a role model who shared my orientation. So I treasure these intergenerational bonds.”

Despite a new generation, the fate of the Pines is far from certain. None of the beach houses are protected from developers and many of their owners have no direct heirs. A precarious future awaits, although Rawlins says there is also an opportunity for a conversation about whether deeds can be changed to protect the integrity of the architecture.

Rawlins describes new builds that have emerged with fences and sod lawns – features that would have left Gifford and his contemporaries aghast.

“It’s kind of just the creeping of typical suburban values into a very unique landscape,” he argues. However he refuses to condemn these buildings. Rawlins saying he would rather educate their owners. It’s clear that this isn’t merely a matter of architecture, but the ideology and social history ingrained in the Pines’ timber.

“Even as it becomes safer for gay people to choose any number of leisure destinations, my hope is for Fire Island to retain its role as a homeland and a rite of passage” he says, “a place where one finds community and a connection to LGBT history.

“We cannot bring back a lost generation, but we can preserve their most salient artifacts and the environment in which they flourished.”