Today’s explorers can livestream around the world as they plunge deep into bottomless ocean chasms.

But 100 years ago, a voyage on a ship meant saying goodbye to loved ones, potentially forever.

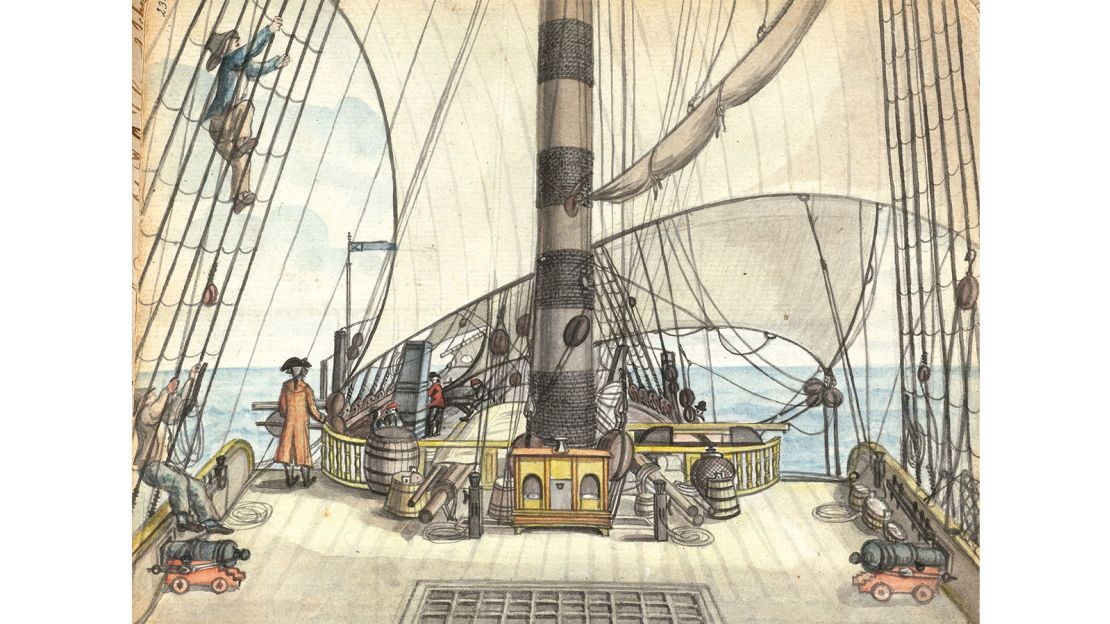

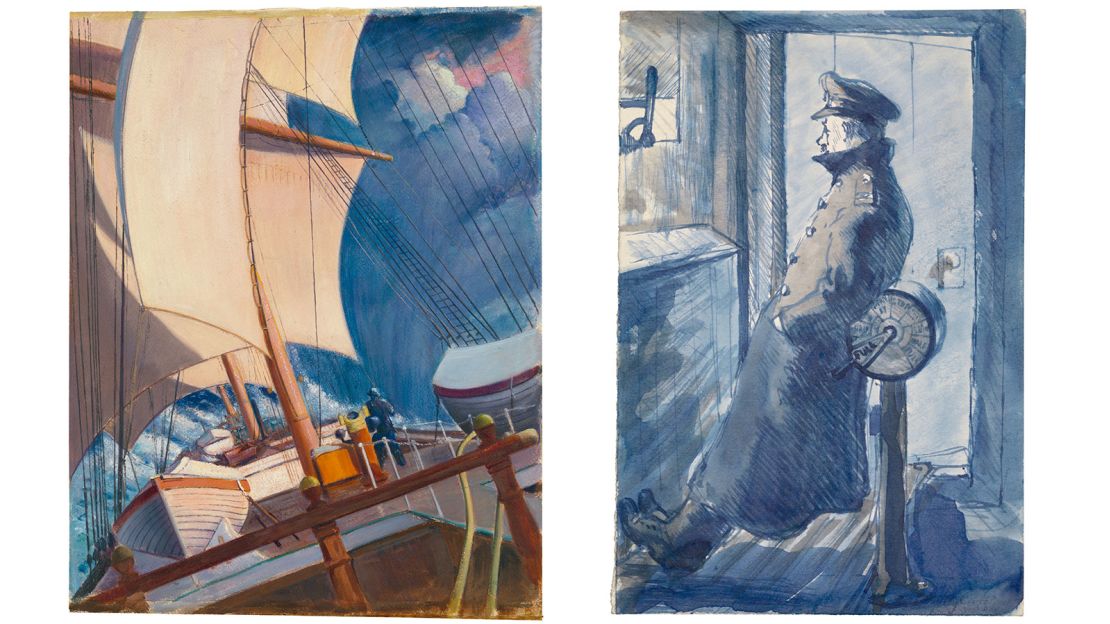

And the absence of smart phones, the old-time equivalent of posting photos on Instagram was sketching scenes from travels in a journal, knowing they might never be seen by another soul.

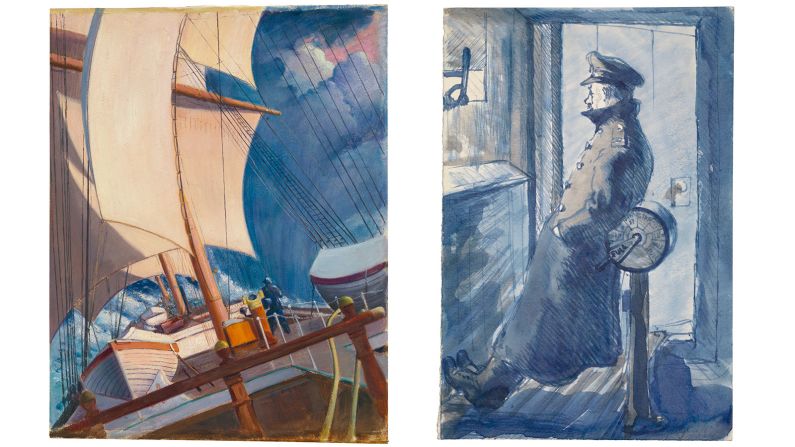

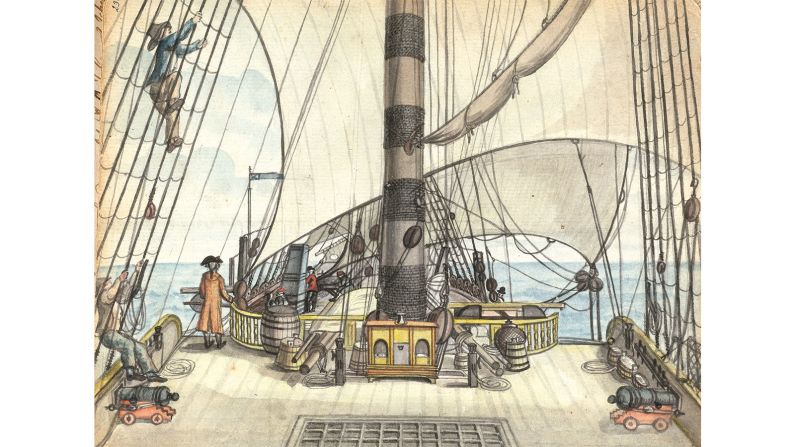

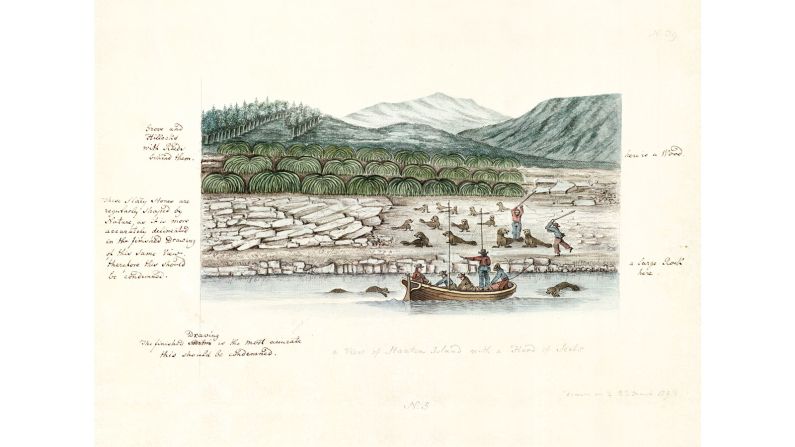

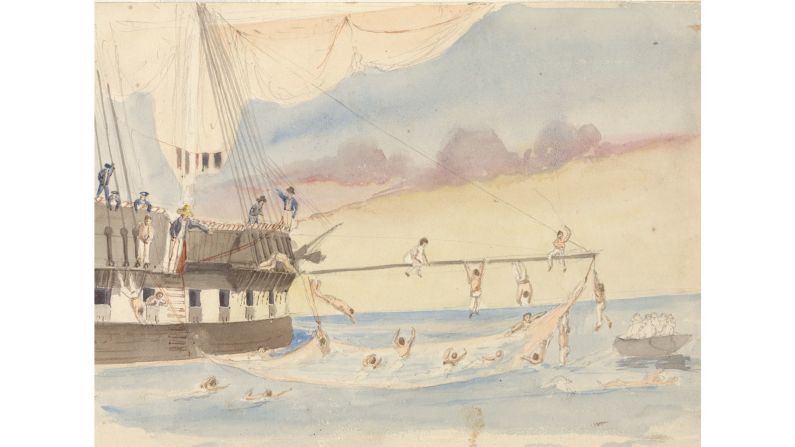

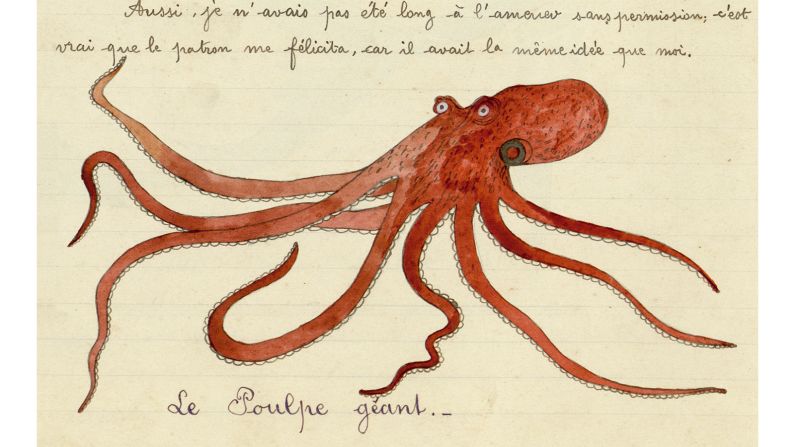

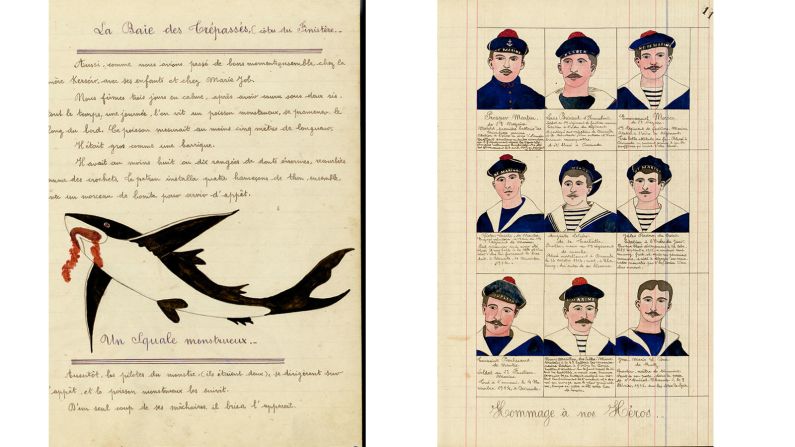

Author, historian and traveler Huw Lewis-Jones has compiled intricate and striking images drawn by sailors into a new book: “The Sea Journal: Seafarers’ Sketchbooks.”

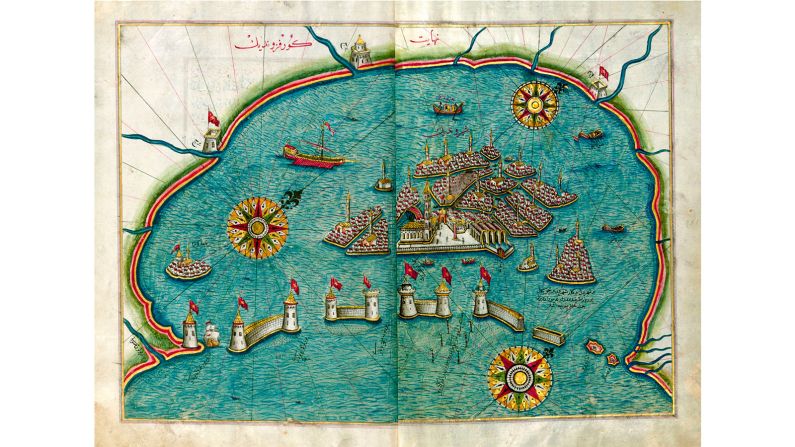

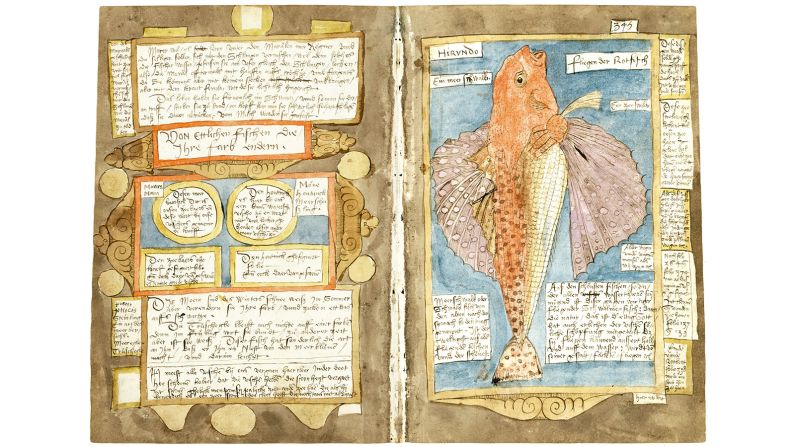

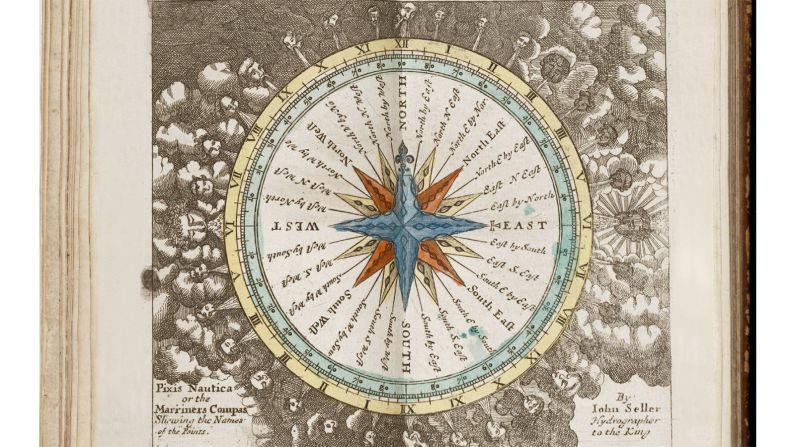

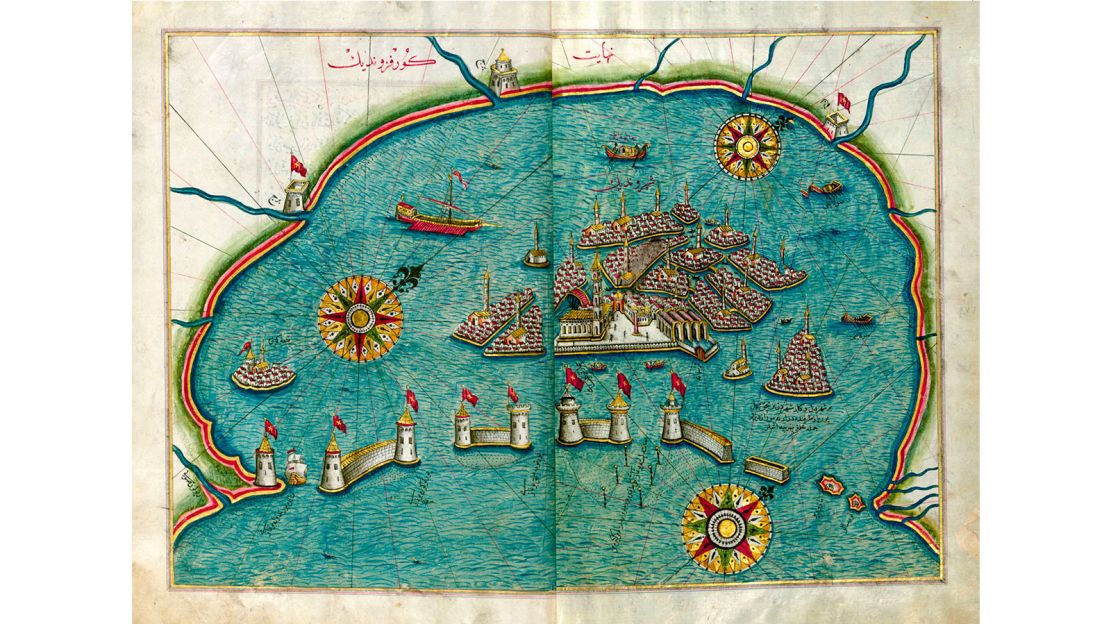

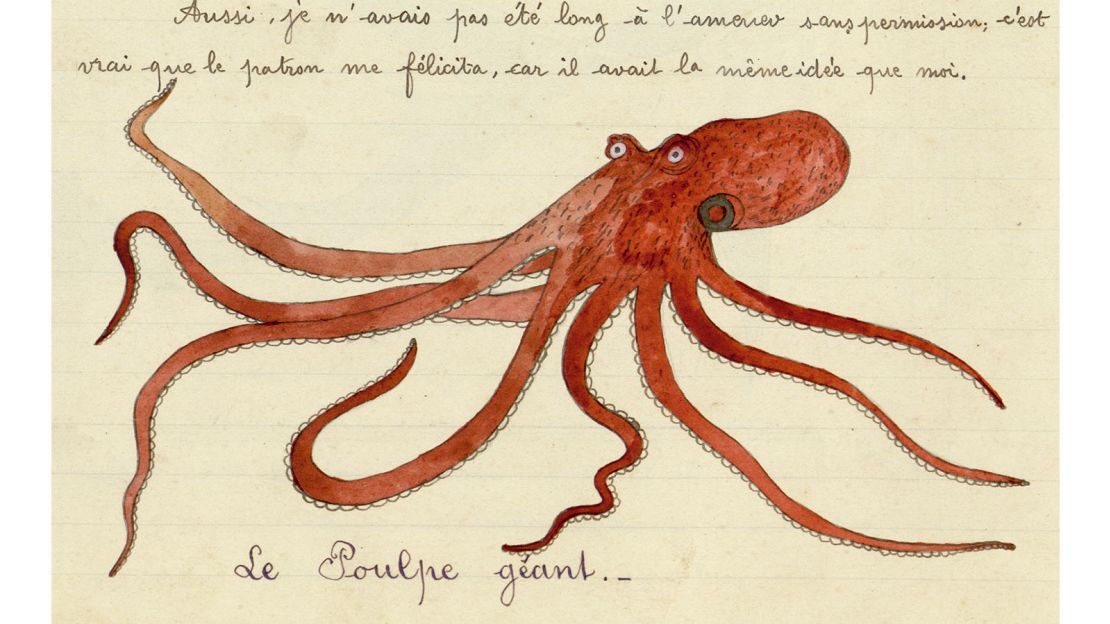

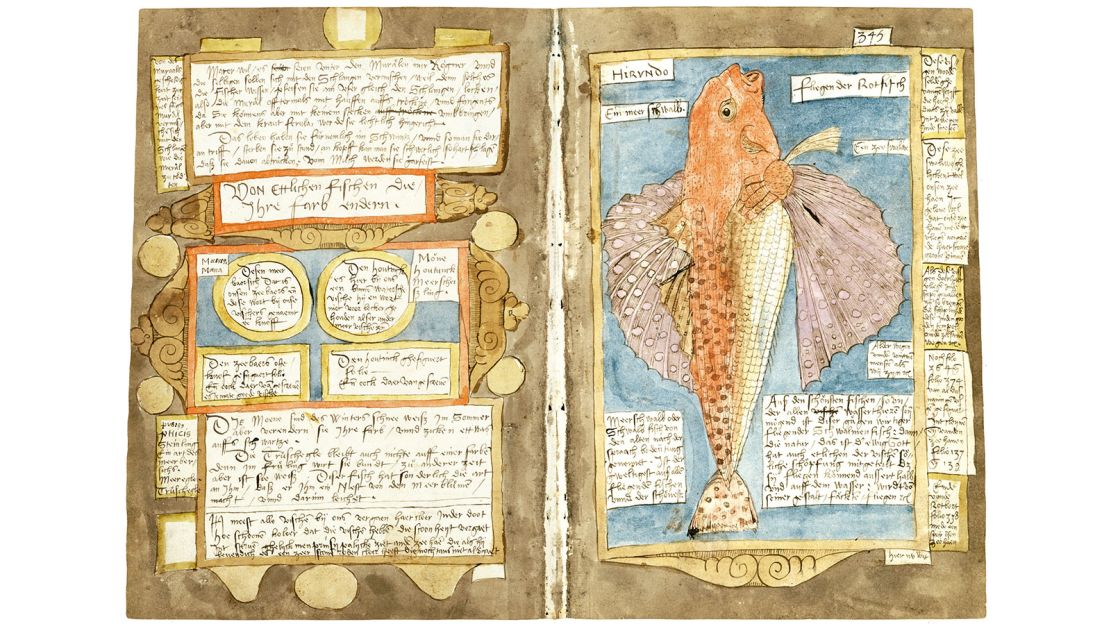

Plates from the book include vibrant maps of the Venice Lagoon, witty cartoons of fellow sailors, descriptions of discoveries and detailed diagrams of sea creatures.

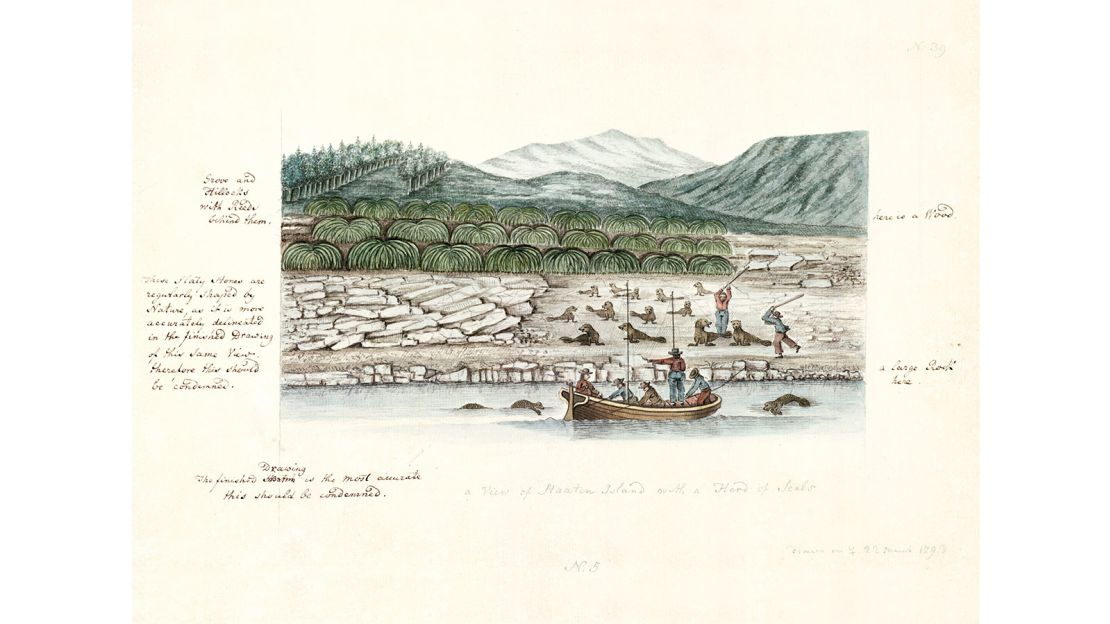

“A lot of the images, they are first-hand images of the understanding of the world changing for people,” Lewis-Jones tells CNN Travel. “That’s what a lot of these big voyages, big expeditions did – change the way people see the world.”

Curious stories

Lewis-Jones has had plenty of his own adventures at sea and on land – making him the perfect person to pen this nautical book.

Currently living in the coastal English region of Cornwall, the author holds a doctorate from Cambridge University and was a fellow at Harvard University. He also worked as a curator at Britain’s National Maritime Museum and the Scott Polar Research Institute.

In his new book, Lewis-Jones delves into the lives of more than 70 mariners, highlighting excerpts from their sketchbooks and evoking their escapades and experiences.

“There are countless stories one could write about the maritime world. It’s obviously infinite, but for me, it was trying to find individuals [whose stories I thought] needed to be told more, or trying to find new ways of telling stories we think we know quite a lot about,” says Lewis-Jones.

With that aim in mind, not everyone in the book’s a household name – even if you’re up to speed with your sailing trivia.

Take the voyages of James Cook. Rather than concentrating on the famed captain, Lewis-Jones highlighted the journals of a lesser-known navigator on Cook’s ship.

Similarly, rather than pinpointing the journals of mythologized Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, Lewis-Jones highlighted photographer Frank Hurley – a key part of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition, but a less famous name.

Defying gender conventions

When you think of ship captains traversing the Seven Seas, you probably think it was an entirely male affair – and men like Shackleton and Cook come to mind.

But Lewis-Jones also highlights some trailblazing women in his pages.

The author writes about Frenchwoman Jeanne Baret, the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. She disguised herself as a boy on board Etoile, the supply ship for Louis-Antoine de Bougainville’s expedition.

De Bougainville was embarking on the first scientific voyage around the world and Baret was part of the team – she became responsible for botany collection during the trip.

Her story echoes that of Rose de Freycinet, who stowed away on her husband’s ship in September 1817, also disguised as a man.

De Freycinet spent the next three years on a scientific expedition to the Pacific and Australia, coming face to face with pirates, malaria and deadly snakes.

She documented her life on board in letters sent back home to a friend.

In the 20th century, German-born Else Bostelmann worked for zoologist William Beebe – who Lewis-Jones calls “the David Attenborough of his day,” referring to the veteran BBC natural history broadcaster.

Bostelmann headed to Nonsuch Island in Bermuda to record marine life in the depths of the ocean. Her vivid, graphic images captured the imagination of a whole generation.

“It was my deliberate intention to try and – even if you’re an expert in maritime history – to find lots of things that could surprise you, or perhaps change the way you think about something,” says Lewis-Jones.

Importance of documentation

Every sketch, plate and painting in the book differs in style, in artistic “merit” and in scientific and geographic accuracy – but regardless, every artifact tells a tale.

These sailors, says Lewis-Jones, inhabited a world “where observation was key.”

“Mariners trained from the very beginning to observe coastlines, observe conditions at sea – navigation required them to make accurate depictions of things – and for many of these sailors, drawing and record-keeping were absolutely a fundamental part of keeping a ship in the direction they [wanted] it to head.”

It was also a way to pass the time on long, sometimes mundane voyages.

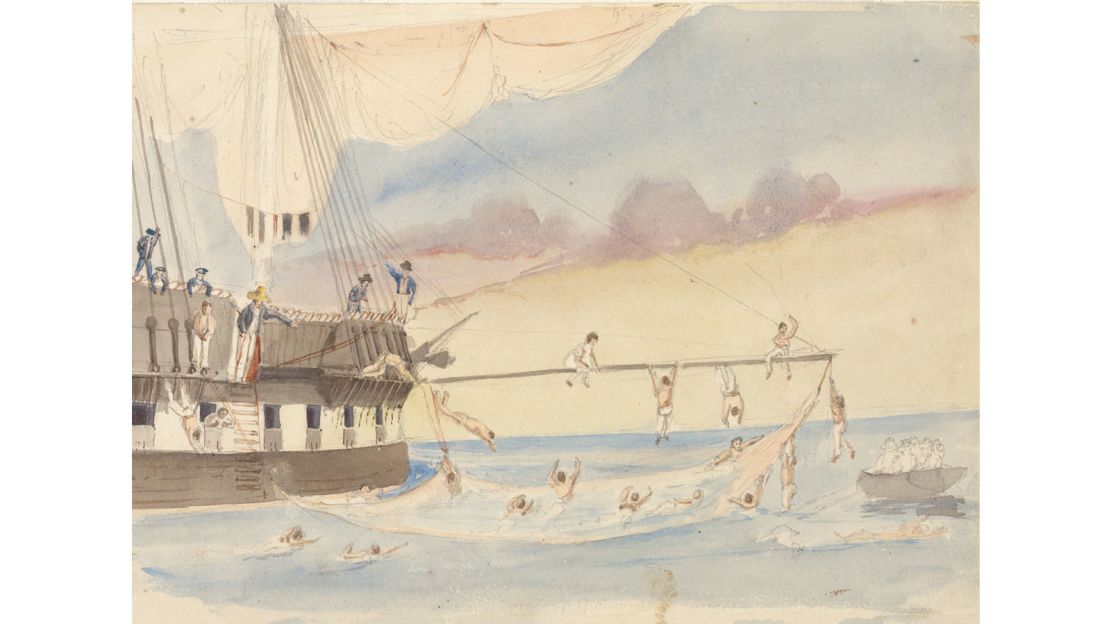

Many sketches highlight the ordinary, “everyday” moments – such as sailors bathing in the sea.

“For many of these people, writing a journal, sketching, became a way of dealing with boredom or anxiety or the dangers they were facing,” says Lewis-Jones.

The dangerous, unpredictable nature of life at sea encouraged mariners to document their experience. There was always a chance their journal would outlive them, and in several cases, this is what happened.

Nearly 500 years ago, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan led the first expedition crossing the Pacific Ocean.

Magellan didn’t survive the journey, but his journal did.

“His depictions – often for the first time – of islands or peoples encountered give an amazing insight into the knowledge that world knowledge is really just beginning,” says Lewis-Jones.

Changing world

On his modern-day expeditions, Lewis-Jones snaps photographs on his smart phone – but, he says, he still keeps a journal and encourages other forms of documentation too.

“The ocean is unchanged – the dangers are still very, very, very real,” he says. “I’m not an explorer – but I travel to the polar regions on ships and I see the value in often, on some expeditions, taking artists and photographers with us.”

The book’s beautiful to thumb through – and readers could easily be left with the impression that all 18th-century seafarers were also talented artists.

But Lewis-Jones stresses not every sea journal is aesthetically pleasing.

“I’m equally interested by pages and pages of scribbling text, with spots and stains from the blubber stove or things torn out,” he says.

After all, although it’s visually enticing, the book’s not really about showcasing nice paintings of boats.

“Yes, it’s about the ocean world, the maritime world, how the way in which we understand the ocean world has changed through time – but ultimately, it’s about human curiosity and that’s pretty universal in the journals,” says Lewis-Jones.

“That’s one of the things that […] unites them all – people are bored sometimes and fearful other times – but ultimately curious enough to sit down and put what they’re witnessing in paint.”